11 Pasifika explorers

Europeans and their vessels were objects of great interest to people in the Pacific. Throughout Polynesia, islanders quickly recognised the value of Europeans’ metal tools and sought to exploit their ocean-going prowess. Ahutoru (a Tahitian) reached France in 1769, courtesy of Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s expedition. He was the first Tahitian explorer to set off for Europe, but not the last. Other Tahitians, quickly followed by people from other island groups, seized early opportunities to travel on European vessels. As European voyages to the Pacific increased in number and frequency, Pasifika began to travel widely and to exploit new opportunities for employment, and for adventure.

When Europeans arrived in Oceania they encountered societies with strong cultures of voyaging and exploration. The islands of the Pacific were peopled because islanders were skilled navigators who both travelled between the island groups of central Polynesia and undertook adventurous voyages into previously unknown regions. Voyaging to the far corners of Polynesia—Hawai’i, Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Aotearoa (New Zealand)—no longer occurred by the time of European arrival in Oceania, but Polynesian vessels were capable of reliably covering enormous distances. When European vessels began to call at Pacific Islands, they represented a new means of travel, but not a new relationship with voyaging.

Ahutoru was the first Tahitian to reach Europe and remained in France for a year. He enjoyed his time there, feted as an intriguing and attractive exotic specimen, but died during the voyage meant to return him to Tahiti. The second Tahitian to set off for Europe was Tupaia, accompanied by his servant Taiata. Tupaia was a priest and navigator who played an important role in the Endeavour’s voyage in the Pacific, but neither Tupaia nor Taiata survived the voyage to Europe. The third attempt by Tahitians to voyage to Europe resulted in a successful return voyage by Mai. While Cook did not consider Mai to be the intellectual equal of Tupaia, he was handsome and caused a sensation on his arrival in England in 1774. Mai returned to Tahiti in 1777.

Early travel by Tahitians to Europe fitted with the cultural expectations of both parties. The Pacific has strong traditions of travel; Europeans have a long history of curiosity about people from elsewhere, and a history of importing humans as curiosities for examination and public show. The experiences of the first Tahitians to reach Europe were enjoyable: they were feted and treated well, and at the conclusion of their time in Europe efforts were made to return them home. This was not the experience of all ‘human specimens’, and while the Tahitians travelled willingly, other travellers to Europe had been kidnapped, deceived, or otherwise exhibited without full consent. Indigenous peoples from the Pacific, and then from Australia, continued to be of interest to European audiences, but the hospitality accorded to Ahutoru and Mai was not extended to later travellers. The European (and then North American) appetite for human exhibitions was such that between 1800 and 1958 35,000 individuals were exhibited around the world, and those people were seen by over one billion spectators. However, many of those individuals were coerced to travel, and many did not survive to return home.

Not all the Pacific travellers who used European expeditions of exploration as transport chose Europe as a destination. Joining the same expedition as Mai, the Tahitian travellers Porio, and then Hitihiti, travelled on the Resolution with Cook. Porio (and a woman who stowed away) travelled within the Tahitian group. Hitihiti visited Tonga, Aotearoa, voyaged in Antarctic waters, visited Rapa Nui, the Marquesas Islands and the Tuamotu Archipelago, then returned to Tahiti. Cook’s third voyage also attracted Pacific hitchhikers, in this case Te Weherua and Koa who travelled from Aotearoa to Tahiti. While Hitihiti did not join Cook’s third expedition he became a useful contact point for Europeans in Tahiti. He met with Cook during Cook’s 1777 visit to Tahiti, advised William Bligh in 1788, and travelled with Edward Edwards on the Pandora in pursuit of the Bounty mutineers. Such travellers might not have reached Europe, but they put Europeans and their technology to good use within the Pacific in the late eighteenth century.

Travel aboard European vessels quickly became normalised within the Pacific, particularly after Sydney was established as a permanent European port. As European missionaries entered the Pacific from the 1790s, Pasifika travelled with them as guides and as recently-converted teachers. Whaling ships also came to the region from that period onwards, and Pasifika signed on as crew. Sydney itself became a significant destination where Pasifika could observe a European settlement and access European technology, species, and goods.

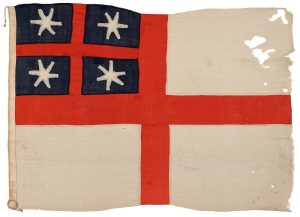

As opportunities arose, large numbers of islanders chose to travel. Hawai’i was the first island group to experience the willing departure of many members of its population, and by the 1840s over 1000 Hawaiians a year left to work. Many Hawaiians worked in the North American fur trade, travelling widely within that continent. The presence of Pasifika sailors on European ships quickly became common as islanders were skilled workers willing to undertake wage labour while embracing the opportunity to travel. European technology enabled Islander travel and was adopted by them. In 1834 the United Tribes’ flag was adopted to register Māori owned vessels of European design.

Aboriginal Australians also travelled on European ships and with European explorers. Bennelong travelled from Sydney to England in 1792 and returned in 1795. His travelling companion Yemmerrawanne died in England. Aboriginal people travelled on vessels exploring the coast of the Australian continent, and they explored the Australian continent as members of colonial expeditions.

Islanders seized the opportunities that European ships represented. They travelled widely, and quickly began to explore Europe. The establishment of the Sydney colony accelerated travel by people from the Pacific. Sydney became a destination in its own right as a window onto European culture and behaviour, and a place to access European resources. Sydney increased the number of European ships in Pacific waters by providing a safe harbour. And Sydney acted as a transit point for Islanders to travel to other European ports worldwide. Islanders quickly began to travel in considerable numbers, exploiting new opportunities for exploration, trade, and paid employment.

Links

Video material

Open access secondary sources

Couper, Alastair. Sailors and Traders: A Maritime History of the Pacific Peoples. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/43913

Jones, Ryan Tucker and Angela Wanhalla, eds. New Histories of Pacific Whaling. Online: Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, 2019. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/2019_i5_layout_v6_0.pdf

Newell, Jenny. “Pacific Travellers: The Islanders who Voyaged with Cook.” Commonplace 5, no.2 (January, 2005). http://commonplace.online/article/pacific-travelers-the-islanders-who-voyaged-with-cook/

Salmond, Anne, Huw Rowlands. “Tupaia the Navigator, Priest and Artist.” Accessed March 31, 2022. http://Tupaia the navigator, priest and artist

Spoehr, Alexander. “Fur Traders in Hawai’i: The Hudson’s Bay Company in Honolulu, 1829-1861.” The Hawaiian Journal of History 20 (1986): 27-66. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/5014724.pdf

Standfield, Rachel, ed. Indigenous Mobilities: Across and Beyond the Antipodes. Canberra: ANU Press, 2018. https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n4260/pdf/book.pdf

Other secondary sources

Howe, Kerry (ed). Vaka moana: Voyages of the Ancestors: The Discovery and Settlement of the Pacific. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

Howe, Kerry. Where the Waves Fall: A New South Sea Islands History from First Settlement to Colonial Rule. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1984.