12 Women explorers

Women are rarely mentioned in histories of Australian and Pacific exploration. A few individual women managed to make their ways onto the ships that explored these regions, but they are often overlooked. The absence of women is itself worth examining, as it raises questions about the way exploration is gendered. The exclusion of women from both sea and land exploration in the Pacific and Australia was the result of structural factors, of expectations surrounding exploration, and of the cultural significance of exploration in European societies. Adventurous European, Pasifika, and Aboriginal women who succeeded in joining expeditions make it clear that women were actively excluded rather than incapable of participation, as do the women who participated in the exploration of other parts of the world. The exploration of the southern continent of Antarctica has been undertaken more recently, and the place of women in that process raises interesting questions about the ways in which exploration frequently remains a masculine enterprise.

When the Pacific was a Spanish Lake, women were at times present on Spanish ships. The early Spanish expeditions were conducted by men alone, but as the Spanish began to seek to establish new colonies in the Pacific women became part of that process. Doña Isabel is notorious as a powerful figure on Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira’s second voyage to the Pacific in 1595-6; she was the wife and heir of the captain. As the Dutch began to intrude on the western edge of the Australian continent, their ambitions for European communities in their trading centres meant that women sailed on the vessels of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The voyages of the VOC were not strictly voyages of exploration, instead carrying trade goods between Europe and the VOC’s base in Batavia. The 1629 shipwreck of the ship Batavia on the western coast of the Australian continent provides a glimpse of the people onboard the Dutch ships skirting the continent; in the aftermath of that disaster a group of mutineers terrorised other survivors, among them women and children.

The expectation that women would form part of European enterprises in the Pacific shifted as exploration became formalised. This process began in the late eighteenth century, and Cook’s Endeavour voyage was an early example of the new style of European voyages taking place within the Pacific. At this time, Pacific exploration became the preserve of European navies, and in this period there were no formal roles for women aboard naval vessels. As a result, women were excluded from exploration.

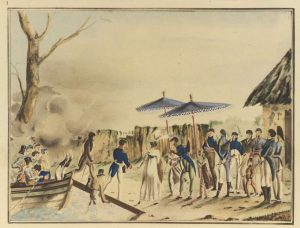

Despite the structural exclusion of women from Pacific exploration, some women managed to travel on European vessels in the Pacific. French naval vessels carried the best-known examples of European women who made their way to the Pacific. Jeanne Baret managed to board Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s 1766-9 circumnavigation as the assistant and valet of the expedition’s naturalist Philibert Commerson. She began the voyage posing as a man, and was unmasked only after it was too late for Bougainville to return her to France. Marie Louise Victoire Girardin successfully signed on to Antoine-Raymond-Joseph Bruny d’Entrecasteaux’s 1791-3 voyage to search for the lost ships of Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse. She presented herself as a male steward, and died during the voyage. Mary Beckwith, a convict, managed to leave Sydney aboard Nicolas Baudin’s voyage in 1802. Rose de Freycinet accompanied her husband Louis de Freycinet during his 1817-20 circumnavigation. Her courage was widely feted, but the voyage took a heavy toll on her health.

The English Navy supported fewer unexpected women voyagers. Joseph Banks arranged to attempt to smuggle a woman onto James Cook’s second voyage to the Pacific, but was himself excluded from the voyage before his plan could unfold. Matthew Flinders attempted to smuggle his wife Ann aboard his ship in 1801 when setting out from England to explore the Australian coast. The subterfuge was detected before Flinders’ ship left England, and it is possible that Ann intended to journey only as far as Sydney. A 14-year-old girl was successfully concealed on board the Bathurst at the start of Phillip Parker King’s 1821 marine survey of Australia. The girl remained concealed until after it was too late for the ship to turn back, but she had an unpleasant voyage as she suffered from seasickness and had to share the rations of the person who smuggled her onboard.

While the ships were within the Pacific, women at time boarded them. During Cook’s second Pacific voyage his ship the Resolution hosted many Tahitian women. One stowed away on board, in order to travel between islands within the Tahitian group. While sailors sought to welcome women aboard, the lack of women on European vessels at times confused the Europeans’ island hosts.

As European exploration of the Australian continent began in earnest in the wake of the establishment of the Sydney settlement, exploration retained its formal, military connections. Within the colony itself, women were a minority. However, women still played roles in the exploration of Australia. During his successful expeditions Thomas Mitchell made extensive use of Aboriginal guides. The guides that signed on for the entirety of his expeditions were male, although Mitchell’s guide, Wiradjuri man Piper, was accompanied by his wife, Kitty, during his travels. Mitchell also made use of temporary guides. In 1836 the Wiradjuri woman Turandurey acted as a temporary guide while Mitchell’s expedition crossed her country. She was able to act as a guide while travelling with her small daughter, Ballandella. Elsewhere in Australia, Ludwig Leichhardt suspected that his progress during his 1844-6 northern expedition was impeded by interactions between his permanent Aboriginal guides and local Aboriginal women. Leichhardt thought his party was greeted with hostility because of his guides’ behaviour.

The Australian situation was extreme in its exclusion of women from recognised roles in European exploration. Australia was far from Europe, and even getting to the starting point for exploration was expensive. As a result, exploration was firmly under government control. During the period in which Australia was explored the Royal Geographical Society in London was experiencing financial difficulties and unable to offer monetary support to the project of Australian exploration, meaning a major private source of funding was unavailable. In contrast, the African continent was less expensive for European explorers to reach, and more attractive to privately funded expeditions. Women were involved in some famous African expeditions: Lady Florence Baker was recognised as accompanying Sir Samuel White Baker in the 1863 quest for the Nile, May French Sheldon circumnavigated Lake Chala in 1891, and Mary Hall traversed Africa from the Cape of Good Hope to Cairo in 1904.

The gradual inclusion of women in the exploration of the southern continent of Antarctica offers insight into the exclusion of women from exploration in earlier periods. Antarctic exploration remains a concern largely under government control (Antarctic bases are funded by a variety of national governments and reaching them generally requires the use of military transport). The admission of women scientists to Antarctic research projects was a slow process, and women have encountered barriers based on their gender. One of those barriers is a sense that Antarctica is a place for masculine adventure, and that the presence of women diminishes the heroism displayed by male, polar heroes. Such a consideration might earlier have excluded women from the adventure of exploration: their presence threatened to make it look too easy.

Women were largely effectively excluded from the European exploration of Australia and the Pacific. Some women managed to participate in various ways, but taking up a formal role on naval vessels and government-sponsored expeditions was almost impossible. Some European women managed to disguise themselves (or otherwise conceal their presence aboard) until the ships carrying them had passed the point of no return. Some indigenous women both in Australia and the Pacific managed to join expeditions in temporary capacities. The presence of these adventurous women, and of women scientists who have overcome gendered barriers to participate in polar research, points to the way in which exploration is not naturally an exclusively male adventure, but one from which women have been actively excluded.

Links

Explorer Journals

Brunt, Kelly. “Notes from the Field.” Last modified January 3, 2020. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/blogs/fromthefield/category/icesat-2-antarctic-traverse/

Hall, Mary. A Woman’s Trek from the Cape to Cairo. London: Methuen & Co, 1907. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/womanstrekfromc00hall

Sheldon, Mary French. Sultan to Sultan: Adventures Among the Masai and Other Tribes of East Africa. Boston: Arena Publishing Company, 1892. https://archive.org/details/sultantosultanad00shel

Video material

Open access secondary sources

Blackadder, Jesse. “Frozen voices: Women, Silence and Antarctica.” In Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections. Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel, 169-177. Canberra: ANU Press, 2015.http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p316261/pdf/Frozen-voices-Women-silence-and-Antarctica.pdf

Booker, Maïa. “Breaking the Ice Ceiling: The Women Working in Antarctica Today.” Time, March 8, 2019. https://time.com/longform/women-antarctica-iwd-scientists-explorers/

Bryant, Myffanwy. “The Extraordinary Circumnavigation of Jeanne Baret.” MuSEAum Blog, July 27, 2020. https://www.sea.museum/2020/07/27/the-extraordinary-circumnavigation-of-jeanne-baret

Lewander, L. “Women and Civilisation on Ice.” In Cold Matters: Cultural Perceptions of Snow, Ice and Cold. Edited by Heidi Hansson and Catharine Norberg, 89-104. Umeå: Umeå University and the Royal Skyttean Society, 2009. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:231857/fulltext01#page=89

Nash, Meredith, Hanne E. F. Nielsen, Justine Shaw, Matt King, Mary-Anne Lea and Narissa Bax, “‘Antarctica Just has this Hero Factor…’: Gendered Barriers to Australian Antarctic Research and Remote Fieldwork.” PLOS (2019): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209983

Reghenzani, Christine. “Women Serving in the Royal Australian Navy: The Path Towards Equality 1960 to 2015.” PhD thesis, James Cook University, 2016. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/46655/

Other secondary sources

Bell, Morag and Cheryl McEwan. “The Admission of Women Fellows to the Royal Geographical Society, 1892-1914; The Controversy and the Outcome.” The Geographical Journal, 162 no. 3 (1996): 295-312.

Bonatti, Enrico, Kathleen Crane. “Oceanography and Women: Early Challenges.” Oceanography, 25, no. 4 (2012): 32–39.

Fishburn, Matt. “Phillip Parker King’s Stowaway.” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 103, no. 1 (Jun 2017): 80-93.

McCahey, Daniella. “‘The Last Refuge of Male Chauvinism’: Print Culture, Masculinity, and the British Antarctic Survey (1960-1996).” Gender, Place & Culture (2021): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2021.1873746

Mccarthy, Michael. “Rose de Freycinet and the French Exploration Corvette L’Uranie (1820): A Highlight of the ‘French Connection’ with the ‘Great Southland’.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 34, no. 1 (2005): 62-78.

Ridley, Glynis. The Discovery of Jeanne Baret: A Story of Science, the High Seas, and the First Woman to Circumnavigate the Globe. Pymble, NSW: Fourth Estate, Harper Collins, 2010.