Module 3. Risk management process by life cycle phase

The project life cycle commonly consists of 5 key phases: initiation, planning, execution, monitoring and controlling, and closure/handover. Project risk management occurs throughout the life cycle and the process differs depending on the phase.

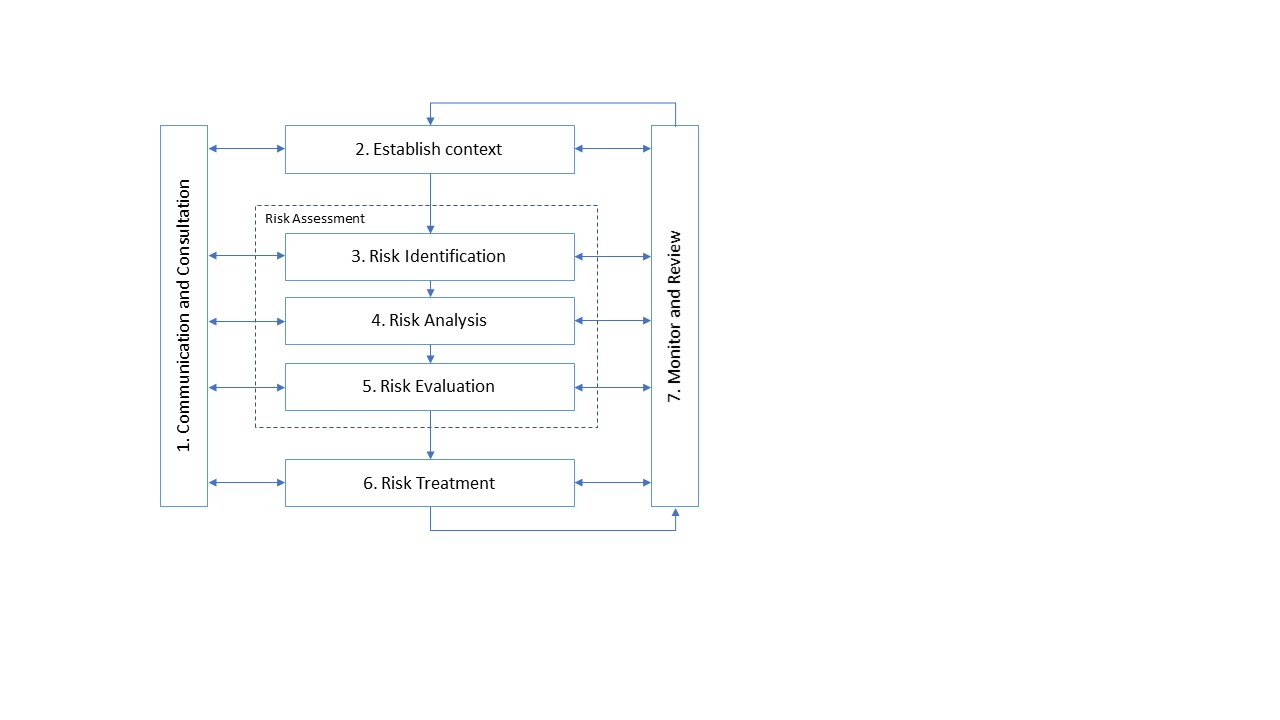

ISO 31000 Risk management

Risk management within a project is a process of identifying any potential risks prior to project commencement and creating a plan to mitigate risks and/or prevent them from occurring. Therefore, risk management requires taking an informed approach to understanding a project’s risk appetite. The most common approach to managing risks is using the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 31000 approach (ISO 2018). The ISO 31000 considers that all organisations face numerous internal and external factors and influences which add uncertainty to achieving objectives (ISO 2018). The ISO 31000 is outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3. ISO 31000 – authors’ interpretation based on the ISO 2018 source, by Carmen Reaiche, Samantha Papavasiliou and Frank Anglani, licensed under CC BY (Attribution) 4.0

The process for the ISO 31000 (ISO 2018) is outlined below.

The process for the ISO 31000 (ISO 2018) is outlined below.

- Communication and consultation. This step assists the project team and stakeholders to understand the risk (ISO 2018). This process seeks to promote awareness and understanding of risks, using consultation to obtain feedback to inform decision-making. Collaboration between stakeholders will assist in obtaining factual, timely, relevant, accurate and understandable information. Both internal and external stakeholders need to be part of the steps within the risk management process.

- Establish context. Context within the risk management process needs to be established by developing an understanding of the internal and external environment in which the organisation operates (ISO 2018).

- Risk assessment. This is the process of identifying, analysing and evaluating risk. Risk assessment needs to be systematic, iterative and collaborative, using the stakeholders’ knowledge. It should be based on the most recent information and supported by further research as required.

- Risk identification. This is the process of finding, recognising and describing potential risks which can support or threaten a project achieving its objectives (ISO 2018). The project team should use a wide range of techniques to identify risks which affect one or more objectives.

- Risk analysis. This is a comprehensive analysis of risk, based on its characteristics (ISO 2018). This involves considering risks generally, their sources, consequences, likelihood, triggers, contingencies, controls and control effectiveness. A key consideration is the risk exposure, which is the risk likelihood and consequence levels. A risk can have numerous causes and consequences and affect multiple objectives or goals.

- Risk evaluation. This process is used to support decision-making. It involves comparing the results of the risk analysis process to the pre-defined risk criteria which outlines when further action is required (ISO 2018). This can lead to a decision to transfer, avoid, treat/mitigate, approve, or reject.

- Risk treatment. This requires selecting and implementing options to address different risks. It includes determining risk treatment options, implementing the treatment, reviewing effectiveness, determining if the remaining levels of risk are acceptable and, where necessary, taking further action (ISO 2018).

- Monitor and review. This is the assurance process which determines the improvement of quality and effectiveness in the design, implementation and outcomes (ISO 2018).Iterative reviews of risk management processes help determine if the treatments that are used in response to risk are effective or not.

The ISO 31000 is an iterative process which helps the project team establish strategies and informed decision-making for risk (ISO 2018). Each activity associated with risk management requires interactions with stakeholders, considering internal and external contexts, the effectiveness of treatments and the overarching completeness of the identification process. Let’s look into the different risk management processes across the project life cycle.

Phase 1: Initiation

The project initiation phase is the start of the project. This requires establishing why a project is underway, its value, and how buy-in from the organisation and sponsors will be obtained (PMI 2021). This phase is critical to developing a successful project. There are a number of failures, issues, problems and risks which can occur in this phase. Approximately 65% to 75% of projects fail due to risks or issues which occur during the project initiation process (Andriole 2021).

The project initiation phase requires consideration of unknown issues that could arise. There are more unknowns at the beginning of a project, as many of the deliverables, requirements and outcomes are unclear. Risk analysis at the initiation phase requires weighing up the potential risks compared to the potential benefits, which will support an understanding of whether or not the project is worthwhile.

The most common risks:

- No clear business or organisational strategy. The benefits for the project do not clearly link back to the organisational objectives, future plan or strategies.

- Lack of capabilities, skills and resources. Organisations do not always have the right resources, skills and capabilities required for their proposed project.

- Lack of stakeholder support. Ensuring that key stakeholders are aware of the project, its value and why it is underway is vital to success.

A risk management framework should be reviewed and tailored to outline specifics within the project risk management plan in the initiation phase (PMI 2021). The risk management plan should include at a minimum:

- possible risk sources and categories

- identification of project risks

- documentation within an influence and likelihood matrix

- risk response and action plan (also referred to as contingency plan)

- risk threshold and metrics during closure.

These elements will be detailed in Phase 2: Planning, below.

Phase 2: Planning

Once a project has been agreed to or approved, it moves onto the planning phase. A key component of the planning phase involves expanding on the risk identification process.

The planning phase of the project requires the project manager and team to document in detail the objectives, goals and requirements that the project seeks to achieve (PMI 2021). These are called the Critical Success Factors (CSF), which are the elements within a project deemed critical to the project achieving its goals (Bennet 2017). By describing these factors or requirements, project team members, stakeholders and sponsors have a consistent understanding of what they are aiming towards.

Risks are things which can threaten, prevent or support the completion of the CSFs within the project. Risks can be positive or negative. A positive risk is an event which poses an opportunity for a project, whereas a negative risk presents a challenge or issue which needs to be overcome (Bennet 2017). Keeping this in mind, risk planning involves identifying the important risk events (either positive or negative), their prioritisation and evaluation, and the process of developing responses.

There are 3 primary steps which occur during the project planning phase for risk management.

Step 1. Identification

The risk identification process requires creating the risk register and the risk breakdown structure (RBS) and completing a risk analysis (PMI 2021). However, the process starts with identifying potential risks:

- Ask ‘what if?’ questions.

- Work with subject matter experts and project stakeholders to brainstorm.

- Analyse previous similar projects, looking at what risks and issues arose for them.

- Analyse the organisational process assets to understand the current organisational processes and any shortfalls or potential gaps.

- Make clear any assumptions and develop task dependencies within the project scoping discussions.

- Look at previous project experience.

- Consider and discuss the worst-case scenarios.

Table 7 outlines some of the primary sources of risk identification.

Table 7. Risk sources

| Risk Source | Description |

| Risk repository | A risk repository outlines historical data for risks that occurred within previously completed projects. |

| Risk identification checklist | Risk identification checklist outlines questions which assist in identifying any gaps or risks within the project space. |

| Subject Matter Expert (SME) Judgment | Brainstorming and/or interviewing with SMEs. This can include experienced project team members, stakeholders and technical experts. |

| Project status | Status meetings, reports, progress reports, quality metrics. This provides information on the current state of the project, issues/risks faced, and violations to baselines. |

In addition to risk sources, risks can be identified by exploring the different risk categories (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008). The risk category list is outlined in Table 8. It shows key areas which are prone to risks occurring, outlining the technical and organisation risks with a set of standard categories based on the project type.

Table 8. Risk categories

| Project Risk Management | Organisational Risks | Technical Risks | Commercial Risks | Environmental Risks |

| Scope | Leadership | Requirements | Contracts | Politics |

| Complexity | Responsibility | Technology | Resources | Law |

| Schedule | Support | Software | Suppliers | Competitors |

| Budget | Commitment | Interface | Financials | Clients |

| Communications | Resources | Performance | Profits | Stakeholders |

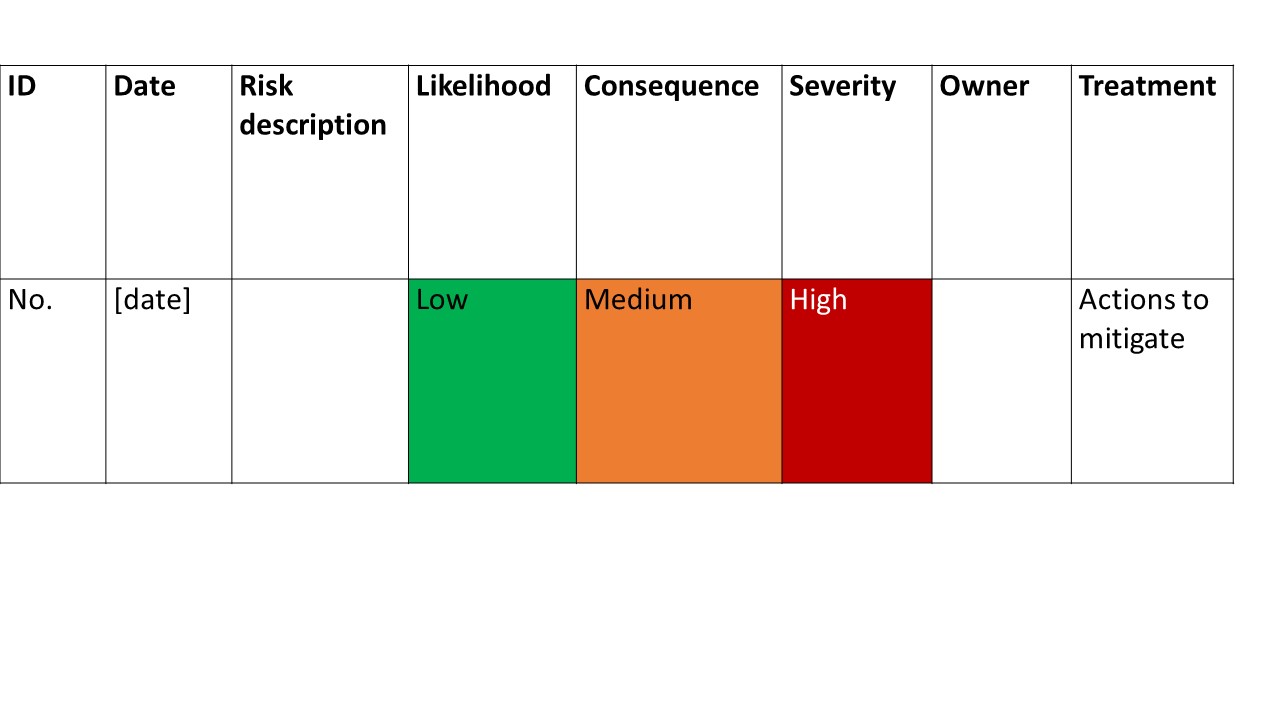

These techniques can help us to identify risks early in the planning phase and are documented within the risk register. Table 9 provides an example of a risk register and suggested headings.

Table 9. Example of headings within a risk register

The risk register includes an itemised list of the identified risks, and it is a primary component of the project risk management plan (PMI 2021). The identification process requires the project manager and the project team to consider what the potential risks are, how they could affect the projects CSFs and when they could occur. Project teams can go overboard on the number of risks identified. It is recommended that only risks which have more than a 5% chance of occurring are noted.

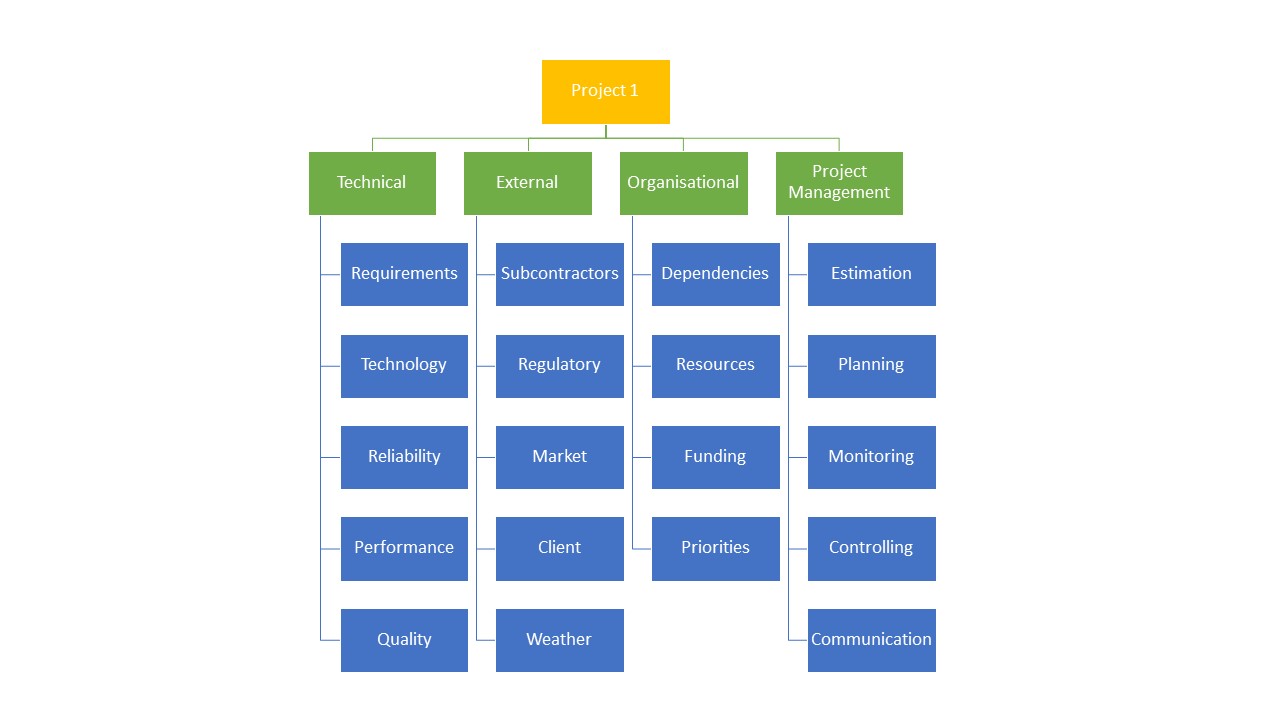

Additional documentation around risk management can include the creation of an RBS. This requires breaking the risks into key categories, which systematically sorts potential risks (PMI 2021). An example of an RBS is outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4. RBS example, by Carmen Reaiche, Samantha Papavasiliou and Frank Anglani, licensed under CC BY (Attribution) 4.0

Not all risks are identified within the planning phase. Project stakeholders, sponsors and managers are aware that it is not possible to identify all risks – that is why it is necessary to have a process in place if an unplanned for risk arises in order to respond appropriately.

Step 2. Evaluation and prioritisation

The next step is evaluating the likelihood and consequence of each potential risk and prioritising these risks. The most common way to determine the risk likelihood and consequence is:

Both probability (likelihood) and impact (consequence) need to be understood and prioritised. This process requires prioritising risks to ensure that stakeholders understand where their identified risks fit (Hillson and Hulett 2004). Where risks have been identified, they need to be evaluated, either qualitatively or quantitatively, to determine their level of influence and consequence on the project. This will ensure that appropriate steps can be planned to mitigate or treat them. The list below outlines the probability (likelihood) of risk occurring and the risk impact (or consequence).

There are a number of ways to assess the likelihood and consequence of a potential risk. Qualitative risk assessment tools include:

- Impact of the risk on the total project. Consider the effect of the risk on the entire project – for example, identify if the risk impacts an activity along the critical path of the project.

- Combined impact of risks. Consider the likelihood and consequence of related risks on activities within the critical path.

- Risk assessment surveys. Complete data collection surveys to obtain subject matter experts’ opinions about their perceived level of likelihood or consequence of risks.

- Impact assessments. Consider the likelihood and consequences of the risk’s occurrence across different scenarios.

Qualitative risk assessments can be done in isolation or completed with the support of quantitative risk assessments. Quantitative risk assessment tools include:

- Sensitivity analysis. This is a technique which helps understand the risks with the highest likelihood to impact the project. This analysis reviews the level of ambiguity of project components because these can affect the project objectives when all other parts of the project are meeting their planned baseline.

- Expected Monetary Value (EMV) analysis. This is a mathematical model which calculates the consequence of future scenarios which could happen (EMV = Risk Probability * Risk Impact).

- Decision tree analysis. A schematisation and calculation method for gauging the consequences of a chain of multiple choices in the presence of ambiguity.

- Simulation. A project model interprets the risks quantified by their likely consequence on project objectives. These link back to the total project objectives. Project simulations follow computer models to evaluate risk, and these determine the likelihood and consequence on budget or schedule. Simulations often use the Monte Carlo analysis.

- Empirical benchmarking methods. Historical project data is used to determine triggers and factors causing risks. These are used to determine contingencies which were used in similar historical projects.

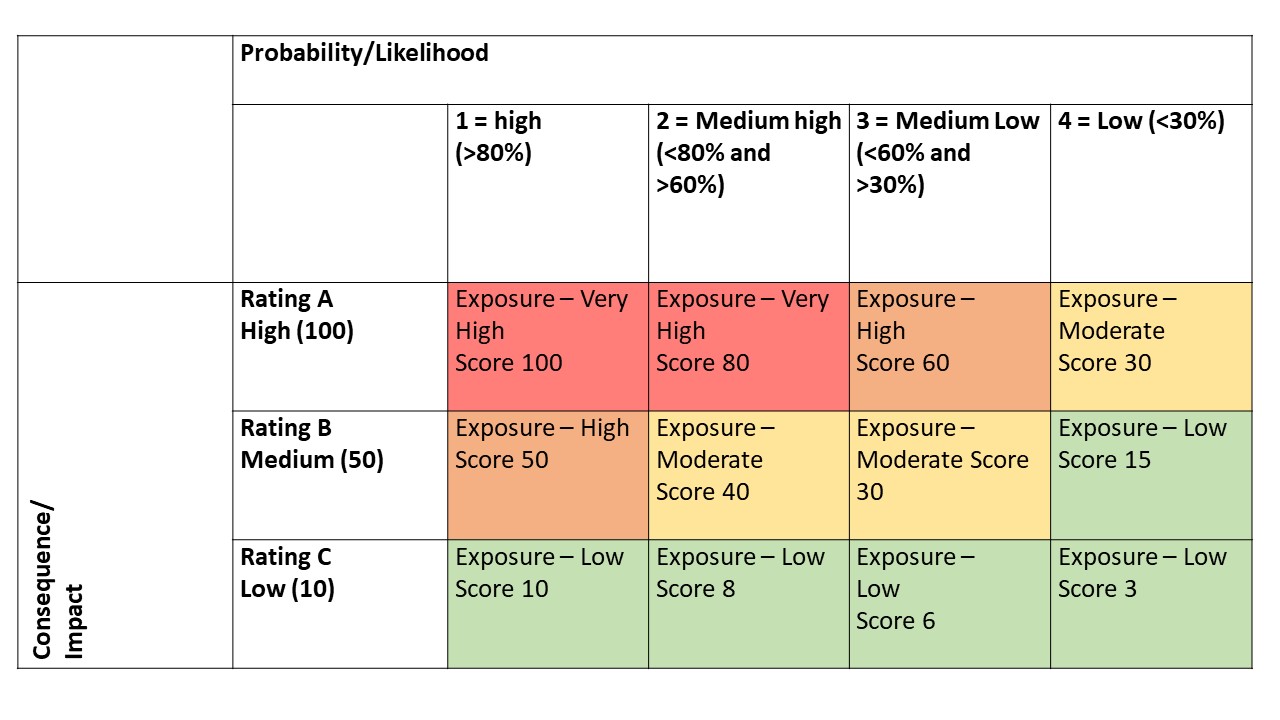

The most common approach to understanding risk likelihood and consequence involves making a judgement call. This call includes determining the likelihood or probability of the risk occurring as a percentage, and can be broken down into 4 categories (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008):

- High probability of occurrence: >80%

- Medium-high probability of occurrence: <80% and >60%

- Medium-low probability of occurrence: <60% and >30%

- Low probability of occurrence: <30%

Alternatively, the consequence or impact of the risk occurring can be ranked. These can be broken down into 3 categories (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008):

- High: catastrophic impact on outcomes or deliverables (Rating A – 100).

- Medium: critical impact on outcomes or deliverables (Rating B – 50).

- Low: marginal impact on outcomes or deliverables (Rating C – 10).

Table 10 Provides a guideline for likelihood and consequence within the risk matrix. This is broken into the 4 elements of the Iron (or project management) Triangle.

Table 10. Impact classification guideline

| Project objective | Rating C (10) | Rating B (50) | Rating A (100) |

| Budget | Budget increase >0% or $0 | Budget increase between 5% and 10% or >$50,000 | Budget increase >10% or >$100,000 |

| Schedule | Schedule delay >0 days | Project schedule delay >1 week (7 days) | Project schedule delay >2 weeks (14 days) |

| Scope | Unnoticeable decrease in scope | Minor scope impact | Scope changes require approval and discussion |

| Quality | Unnoticeable quality reduction | Minor quality reduction (does not impact functionality) | Quality changes require approval |

A risk score or rating represents the thresholds or classifications for risks. This is based on normal conditions; however, there are circumstances where an upgrade is needed. This includes when critical factors could impact the likelihood or consequence, for example:

- Who is the client? What level of importance is placed on the specific stakeholder?

- Is the project or risk management process vital to the long-term relationship between the organisation and stakeholder?

- Is the risk already of concern to the stakeholders or clients?

- What are the potential penalties of not delivering the project in its current form? Or for deviations from scope?

Once the risk has been analysed, the exposure level or risk score needs to be outlined. The risk scope can be determined through the multiplication of the ‘Impact/Consequence Rating’ with the ‘Risk Probability or Likelihood’ (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008). This is shown in Table 11.

Table 11. Risk exposure scores, also referred to as the Impact-Probability or Likelihood-Consequence Matrix

Colours within the matrix outline the urgency of the risk response required as part of the planning and it documents the reporting levels.

Once the urgency and exposure risks have been identified, the next step is to identify the risk occurrence timeframe (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008). The most common timeframes are identified as:

- Near: could occur between now and the next month.

- Mid: could occur within the following 2 to 6 months.

- Far: could occur in a period of greater than 6 months.

In addition to the above risk analysis process, it is important to understand the classification of risks and their impact on project budget, schedule, scope, and quality. This will help create a risk response process.

Step 3. Risk response

The final step in the risk management process is developing the risk response or treatment plan. This is added to the risk register and provides vital information for what actions need to be taken if a risk occurs or is occurring (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008). As risks can be triggered at any stage of the project, the treatment plan requires an appropriate level of detail. The risk response plan requires numerous components, including:

- risk description associated with the risk analysis and assessment

- planned action to respond to the risk arising

- owner of risk response actions

- commitment date required to finalise actions.

The level of detail required for risk management plans will differ depending on their likelihood or consequence (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008).

- For the most significant risks (e.g., high likelihood and consequence), a detailed action plan is necessary.

- For medium risks (e.g., medium likelihood and consequence), a brief action plan will do.

- For small risks (e.g., low likelihood and consequence), no action plan may be required at all.

It is important that all risks within the action plan be allocated to a person who can take the actions required to respond to the risk. The action plan includes the following.

- The response plan

Each risk identified must be documented within the risk register and these need to be discussed with the project sponsors and stakeholders. The process needs to be understood by the project manager.

Action or response plans are not necessary for all risks. There are different responses which can be applied to the risks identified (Kendrick 2019), including:

- Avoid: threat to be eliminated or removed.

- Transfer: shift the risk to a third party.

- Mitigate/treat: take actions to reduce the probability or impact of the risk occurring.

- Accept: where necessary, it may be important to proceed and accept the risk.

The risk response plan needs to consider the impact on schedule and budget. Therefore, when planning a risk response schedule, a budget needs to be outlined as precisely as possible. By being precise in the risk response plan, alternative actions can support the implementation of integrated changes.

Once the response plan is successfully implemented, risk scores can be lowered or adjusted based on the current environment.

- Risk triggers

Each risk trigger needs to be documented within the broader risk register. The triggers can be used to identify the causes or warning signs. Furthermore, understanding triggers can support identifying risks that are about to occur, or provide an indication about certain risks that are likely to occur. Table 12 outlines an example of the risk triggers.

Table 12. Risk trigger examples

| Risk Event | Risk Trigger |

| Schedule delay due to weather | Confirmed extended forecast showing adverse weather is set to occur |

| Limited resource availability | Unexpected leave due to illness |

3. Risk ownership

Every risk must be allocated an owner and this person must be documented within the risk register (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008). A risk owner is the person or position who can monitor the risk and undertake actions in the response plans. This risk owner reports changes to risk status and takes necessary actions.

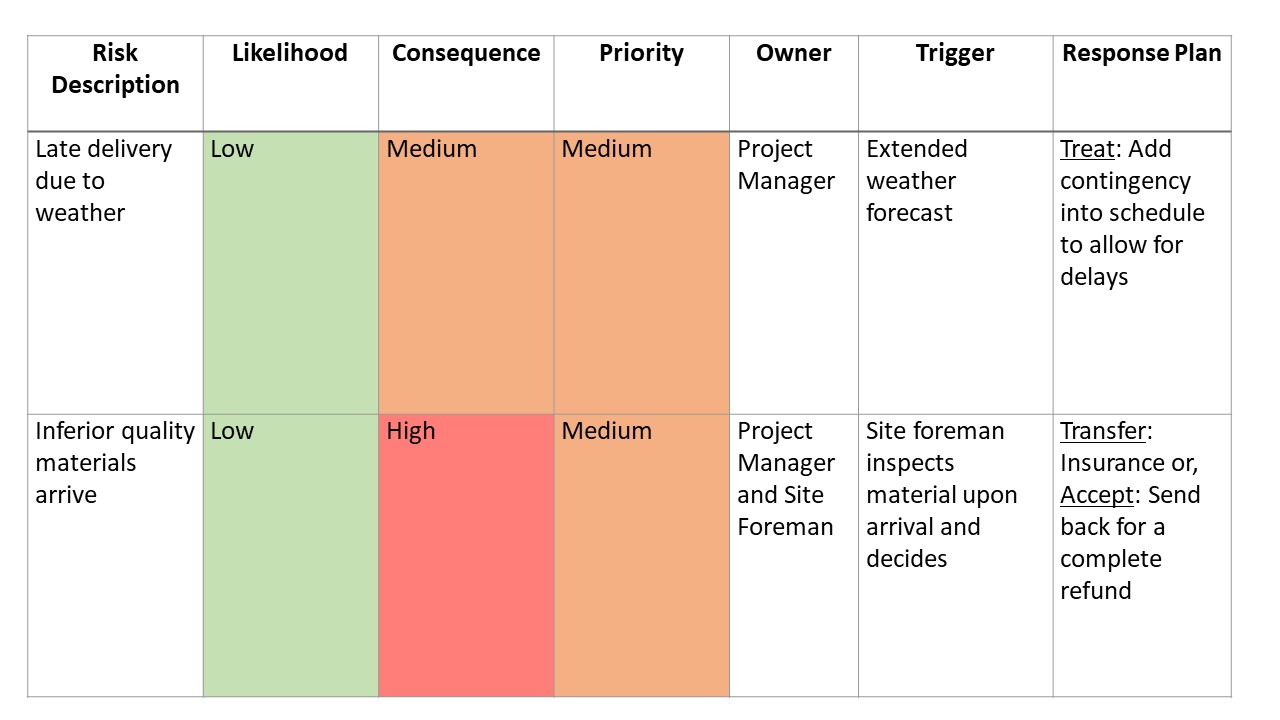

An example of a risk register is outlined in Table 13, showing the different triggers and response plans. The risk register needs to be updated throughout the risk management process and across the project management life cycle.

Table 13. Risk register example

Phase 3. Execution

The project moves into the execution phase when work begins to meet the project goals and objectives (PMI 2021). As the project progresses, more information becomes available, and more risks can be identified and support response planning. This highlights the importance of updating the risk register as new information comes to light.

Phase 4. Monitor and control

The process of monitoring and controlling within project management and risk management is an iterative process which requires ongoing performance and status reporting (PMI 2021). These reports outline the current state of deliverables or outcomes in comparison to the baseline or planned/expected deliverables or outcomes. This is a point-in-time analysis, which is supported by a status report (e.g., quality, progress, follow-up and risk reporting).

Within risk management, the process of monitoring and controlling risk includes:

- identifying new risks

- planning responses for new risks as they arise

- ongoing assessment of current risk status

- documenting any triggered risk conditions

- monitoring whether risks are becoming more likely or consequential over time

- considering long-term planning and management of risk treatment plans.

Key actions required within the monitoring and controlling process include risk reporting and reclassification. Risk reclassification refers to risks which are not ready to be closed, but whose likelihood and consequence decreases over time (due to responses within the action plan). However, not all actions will have been sufficient to address the risks, and more actions may be needed. Next is risk reporting, which is where risk registers require updating. This includes going through risk identification, planning and responses and status updates. The risk register is the primary risk tool and needs to be accessible by all key stakeholders.

The monitoring and controlling process is mandatory in risk management – it is part of milestone and regular project meetings. The frequency of risk management meetings can be altered to meet the needs or risk level of the overall project.

As part of the monitoring and controlling process, the risk thresholds may change. This includes the different priorities, where risks change from higher to lower exposure rates. Risks may decrease in risk thresholds or priorities, and lower ranked exposure risks can then be removed from response plans.

Phase 5. Closure

When the project closure occurs, there needs to be agreement across the stakeholders, sponsors and project team/manager that the risk management plans can be finalised along with the project (PMI 2021). All the risks that occurred need to be documented, and their impact needs to be assessed and documented. Table 14 outlines a documentation example for the close out of a risk management process and corresponding risk register.

Table 14. Close out process of risk register

| Risk | Mitigation | Closure |

| Late delivery due to weather | Use contingency reserve in the schedule to allow for delays. | Confirm the amount of contingency used in the timeframe. |

| Inferior quality materials arrive | Send back inferior quality materials for a complete refund. | Confirm the delays associated with sending back the inferior quality materials. |

A risk score or rating represents the thresholds or classifications for risks (Lavanya and Malarvizhi 2008). This is based on normal conditions; however, there are circumstances where an upgrade is needed, including when critical factors could impact the likelihood or consequence.

Within the closure phase, additional lessons can be learned from the risk management process across the project management life cycle (PMI 2021). For risk management, this includes assessing the efficiency measures for risk metrics and the auditing processes. Risk metrics refer to the overall efficiency of the risk analysis and management. This is measured by capturing key metrics throughout the project, including:

- number of risks that arose

- number of risks identified

- percentage or number of risks recurring

- how the risks, issues or problems faced within the project differed from the plan.

Each of these metrics are documented within the lessons learned and support future project and risk planning.

Risk audits are a process by which an independent analyst assesses the risks and provides recommendations on how to improve maturity or effectiveness of organisational/project risk management processes (PMI 2021). This process includes:

- understanding how good the project team are at identifying risk

- checking how complete the list of risks identified was

- checking the effectiveness of the response plan

- checking for links between the project and organisational risks.

Risk audits are not the adherence to process type audit; instead, they specifically aim to improve risk identification and analysis processes. Through the audit, organisations can set a benchmark for best practices in risk management processes.

A risk audit is comprised of a group of technical or subject matter experts brought together via documentation reviews and interviews. Key outcomes of a risk audit include:

- checklists for evaluating project risks

- identifying the importance of risk analysis categories within the project or organisation

- documenting the key risk categories and triggers

- adding any additional risks which were identified during the risk assessment process and which were missed in early planning

- listing the top 10 project and organisation risks which required the most attention.

Overall, risk management occurs throughout the project life cycle. However, project uncertainty can be hard to predict, and through an end-to-end risk management process, organisations and projects can learn from mistakes or previous projects. Within a project life cycle, appropriate use of risk management supports mitigating crisis situations and improves the chances of successful project completion.

Now let’s review our knowledge:

Key Takeaways

- The ISO 31000 considers that all organisations face numerous internal and external factors and influences which add uncertainty to achieving objectives.

- The risk identification process requires creating the risk register and the risk breakdown structure, and completing a risk analysis.

- A risk score or rating represents the thresholds or classifications for risks.

- When the project ends, all the risks that occurred need to be documented, and their impact needs to be assessed and documented.

References

Andriole S (25 March, 2021) 3 Main reasons why big technology projects fail and why many companies should just never do them, Forbes website, accessed 30 August 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/steveandriole/2021/03/25/3-main-reasons-why-big-technology-projects-fail—why-many-companies-should-just-never-do-them/?sh=4ea2ada4257c

Bennet N (2017) Managing successful projects with PRINCE2, AXELOS, United Kingdom.

Hillson D and Hulett D (2004) ‘Assessing risk probability: alternatives approaches’, 2004 PMI Global Congress Proceedings, Prague, Czech Republic.

International Organization for Standardization (2018) ISO 31000 Risk management guidelines, ISO, accessed 30 August 2022, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en

Kendrick T (2019) Identifying and managing project risk: essential tools for failure-proofing your project, Harper Collins Leadership, United States.

Lavanya N and Malarvizhi T (2008) ‘Risk analysis and management: a vital key to effective project management’, paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2008—Asia Pacific, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA.

Project Management Institute (2021) A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th edn, Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA.