4 Attitudes and Issues

“But all is mortal in nature, so is all nature in love mortal in folly.”

(As You Like It, Act 2, scene 4, lines 54-55).

Above is the opinion of Touchstone, who should know about folly since it is his profession. Rosalind confirms it when she replies, “Thou speak’st wiser than thou art ware of.” Like Shakespeare’s other fools, for example, Feste in Twelfth Night and King Lear’s genuinely wise fool, Touchstone speaks truths that people around him hesitate to acknowledge. But Touchstone differs from Feste and Lear’s fool: he is not merely an observer, but a participant in the folly that he finds in love.

In his analysis of Shakespeare’s Festive Comedy, C. L. Barber writes that Touchstone represents “what in love is unromantic … he embodies the part of ourselves which resists the play’s reigning idealism” (232). Accordingly, it is not love but lust that attracts the sophisticated dweller in courts to the country lass Audrey. Their attraction is hardly “the marriage of true minds” that Shakespeare commends as an ideal in Sonnet 116. Jaques prophecies that, married, Touchstone and Audrey can look forward to a life of ‘wrangling’: “for thy loving voyage / Is but for two months victualled”,[1] (Act 5, scene 4, lines 199-201).

However light-hearted, the condemnation of lust in As You Like It repeats a Christian view rarely questioned in Western countries before the twenty-first century: “But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart” (Matthew 5.28). Shakespeare’s sonnet 129, which begins “Th’expense of spirit in a waste of shame’ condemns lust as ‘perjured, murd’rous, bloody, full of blame, / Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust” (lines 2-3). Touchstone’s lust and its result, a marriage made up of ‘wrangling,’ gives these admonitions a form appropriate for a comedy. According to Barber, “the fool’s cynicism, or one-sided realism, forestalls[2] the cynicism with which the audience might greet a play where his sort of realism has been ignored” (232). You might like to google ‘cynicism’ for its meaning.

Sex is Touchstone’s priority. Audrey’s profession of goatherd has similar connotations. They and their relationship amount to a parody of higher, emotive forms of love. If Touchstone and Audrey provide a gross realist base for Shakespeare’s pyramid of lovers in As You Like It, Sylvius and Phoebe are the idealised pinnacle. As shepherd and shepherdess they belong to the romantic and aristocratic pastoral tradition in art and literature. ‘Pastoral’ comes from the Latin word pastor, meaning shepherd. The tradition found its home in Renaissance royal courts, and was still flourishing in the late eighteenth century when Queen Marie-Antoinette and her courtiers liked to dress up as shepherds and shepherdesses. Aspects of pastoral are present in most of Shakespeare’s major comedies.[3]

In As You Like It Touchstone, Rosalind and Celia are an onstage audience as Corin attempts to guide Sylvius in his infatuation with Phoebe (Act 2, scene 4, lines 19-42). Corin, Rosalind and Celia are again the audience when Silvius woos Phoebe in Act 3, scene 5.

In this latter scene, Phoebe’s arguments rejecting Silvius undermine the ‘courtly love’ tradition mentioned above in Chapter 3. Phoebe debunks the tradition’s pervasive trope that a scornful lady’s eyes shoot darts that ‘murder’ or ‘butcher’ her faithful lover. Rosalind, in the guise of Ganymede, steps in and admonishes both of them: Phoebe has only average looks, she says. Silvius should have more self-respect than to follow Phoebe about, “[l]ike foggy south, puffing with wind and rain” (line 51). This is funny enough, but the comic irony is that even as Ganymede/Rosalind speaks, Phoebe is falling in love with him/her. Love knows no reason!

Rosalind’s admonition to Phoebe recalls Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130, beginning, “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun…” The first twelve lines list how the thick black hair and sallow complexion of Shakespeare’s beloved are less prized than the rosy, golden-haired beauty of courtly ladies of medieval tradition. However, the sonnet’s closing couplet reveals the speaker’s true feelings:

And yet by heav’n I think my love [the dark lady] as fair

And as any she [i.e. woman] belied by false compare [i.e. misrepresented].

By contrast, Ganymede/Rosalind finds nothing attractive in Phoebe’s dark looks:

Od’s my little life,

I think she means to tangle my eyes too!

No, faith, proud mistress, hope not after it.

‘Tis not your inky brows, your black silk hair,

Your bugle[4] eyeballs, nor your cheeks of cream,

That can entame my spirits to your worship. (Act 3, scene 5, lines 48-53)

Rosalind again attacks Silvius’ delusion when she critiques Phoebe’s love poem in Act 4, scene 3. As You Like It creates comedy out of both the goatish attraction of Touchstone and Audrey and the fantasy romance of the pastoral courtly lovers Silvius and Phoebe. Concurrently with these extremes, the play provides an ideal for the audience to enjoy and aspire to: Rosalind’s and Orlando’s mutual, humane, intelligent and passionate love.

“Rosalind and Orlando in Act 1, scene 2” by Shakespeare’s Globe [1:14 mins]:

The question central to As You Like It is: How are the qualities of this ideal love made clear to the audience?

- Act 1, scene 2, lines 243-261 – Rosalind and Orlando separately admit their love to themselves. Find the metaphors in this passage to compare falling in love with a wrestling match.

- Act 1, scene 3 – opens with Rosalind and Celia discussing Rosalind’s new-found love. What does Rosalind say are her symptoms? Find examples of wit and humour in Celia’s and Rosalind’s conversation.

- Act 3, scene 3, lines 155-255 – Celia breaks the news to Rosalind of Orlando’s arrival in the forest. Find examples of teasing, excitement, impatience, humor, hesitancy and uncertainty in their conversation. ( You don’t have to find ALL of them!)

- Act 3, scene 2, lines 299-443 – this is Rosalind’s first exchange with Orlando in her disguise as Ganymede. These scenes can be regarded as the ‘heart’ of As You Like It. In this introduction, Orlando agrees to make the ‘boy’ Ganymede his love ‘curer’. Much of their conversation, now and later, makes fun of the courtly love conventions that Orlando enacts or tries to, for example in his love poems. In this scene, what do Rosalind and Orlando say about:

1) time; 2) the unpredictability of young women who are loved; 3) love as an illness; 4) the physical signs of a lover’s suffering; 5) love as insanity?

Which social class in Shakespeare’s audience do you think would have liked this scene the most—the Queen’s court? middle-class Londoners? The groundlings? (Groundlings stood at eye-level with the stage to watch the play and paid only a penny—i.e., less than AUD $2). Which class in your view does Shakespeare most want to please? - Act 3, scene 4 – Orlando has not kept his promise to meet with Ganymede/Rosalind, and Celia teases her that he is unfaithful. What does Celia compare the supposedly unfaithful Orlando to? Make a list.

- Act 4, scene 1, Line 33- 213 – Orlando continues to apply the conventions of courtly love to his love for Rosalind. For example, when Ganymede/Rosalind says she will not have him, he says he will die. The painting below (ca. 1625-16266, now in the National Gallery of Victoria) dramatises the romantic version of the Greek myth Hero and Leander as told by Christopher Marlowe. How does Rosalind change the story to prove that “Men have died from time to time and worms have eaten them, but not for love” (lines 112-113)? But, in a comic contradiction that again demonstrates love’s irrationality, what does Rosalind reveal to Celia about her feelings after Orlando has left? (lines 228-230). How does Cupid come into this revelation? As shown by her side comments, what is Celia’s assessment of Rosalind and Orlando’s love?

Figure 13. Hero and Leander (1625-1626) by Nicolas Régnier (1591-1667). Oil on canvas. Public domain - Act 5, scene 2 – hope energises the comic suffering of the lovers in this delightful scene, which shows the distance that Orlando and Rosalind have travelled in understanding their mutual love. Rosalind has realised that the time for games is ending. Orlando has two moving lines that show he is ready to graduate from Ganymede’s ‘love school’:

1. “I can live no longer by thinking.” ( line 53)

2. “To her that is not here nor doth not hear.” ( line 113).

Find examples in this prose scene of poetic devices such as repetitions, puns and symmetry.

Finally…

Shakespeare’s pyramid of lovers includes a fourth pair who, because of their social class, occupy a niche near the top.

Celia and Oliver are the most striking example in As You Like It (and possibly in all literature!) of the trope of love at first sight: “There was never anything so sudden but the fight of two rams, and Caesar’s thrasonical[5] brag of ‘I came, saw and overcame.’ They are in the very wrath of love and they will be together. Clubs cannot part them”(Act 5, scene 2, lines 31-33 and 41-43).

Explore the Text

Why does Rosalind’s report of Celia’s and Oliver’s sudden passion mix romantic rhetoric with similes and metaphors of war and violence (e.g. ‘fight of two rams,’ ‘Caesar’s thrasonical brag,’ ‘wrath of love,’ ‘clubs’)?

Even in a romantic comedy, Celia’s and Oliver’s passion and instant desire for marriage seem unlikely. Their attraction nevertheless produces the symmetrical closure in which four couples are united.

A question about ‘Definitions of Love’ in As You Like It that you might like to consider:

How far does Rosalind’s disguise as Ganymede broaden the definition of love so that it includes same-sex-love-between men (Ganymede and Orlando) and between women (Ganymede and Celia?)

The song, ‘Blow, blow, thou winter wind’ brings ingratitude to mind and questions the reality of friendship and love. Later events in As You Like It affirm their reality and truth. Many beautiful renditions of Shakespeare’s song are online. As You Like It upholds the power of love to attract and to remain constant. If they don’t already know it from experience, audiences are assured that love is imperfect but delightful and often funny; that it is one of the best, if not the best, experiences available to humans; and that youth is the best time for loving.

But (again) WHAT about Celia?

From Act 2, Rosalind takes the lead in their friendship: she supports Celia in her state of physical exhaustion and negotiates the purchase of their cottage. In Act 3, Celia continues to be Rosalind’s confidante and witty commentator on Rosalind’s and Orlando’s love exchanges. The magical humour in Act 3, scene 2 of Celia’s withholding, and then imparting, the news of Orlando’s presence in Arden and then her negotiating of Rosalind’s outpouring of questions repays rereading! Celia contributes to Shakespeare’s joyful revelation of the extravagance and extremity of Rosalind’s love for Orlando. Her witness and commentaries ensure that the conversations between the lovers, the ‘heart’ of As You Like It (see above) remain light-hearted. She also aids the play’s joyful interrogation of ‘courtly love’ conventions.

Explore the Text

Find the comic deflations and down-to-earth comparisons in Celia’s following exchange with Rosalind (you might need to find explanations for some of Celia’s similes):

ROSALIND: But why did he [Orlando] swear he would come this

morning and comes not?

CELIA: Nay, certainly there is no truth to him.

ROSALIND: Do you think so?

CELIA: Yes, I think he is not a pick-purse nor a horse stealer

but for his verity in love I do think him as

concave as a covered goblet or a worm-eaten nut.

ROSALIND: Not true in love?

CELIA: Yes, when he is in but I think he is not in.

ROSALIND: You have heard him swear downright he was.

CELIA: ‘Was’ is not ‘is’. Besides, the oath of a lover is

no stronger than the word of a tapster: they are

both the confirmer of false reckonings… (Act 3, scene 4, lines 18-31)

The complex texture of ideas in As You Like It includes debates that are still important to twenty-first-century people. For example:

1. Money Matters

The characters in As You Like It, including those who are most loved by audiences, try to be prudent when it comes to money:

- What financial provision do Rosalind and Celia make when fleeing to the forest? (Act 1, scene 3, line 141)

- What do they end up using their money for?[6] (Act 2, scene 5)

- What money do Orlando and Adam mean to live on after their flight? (Act 2, scene 3)

- How does Oliver’s attitude to money and possessions differ from Orlando’s and Adam’s?

This practical interest grounds As You Like It in the commercial world of Shakespeare and his middle-class audiences.

2. Fortune Versus Nature

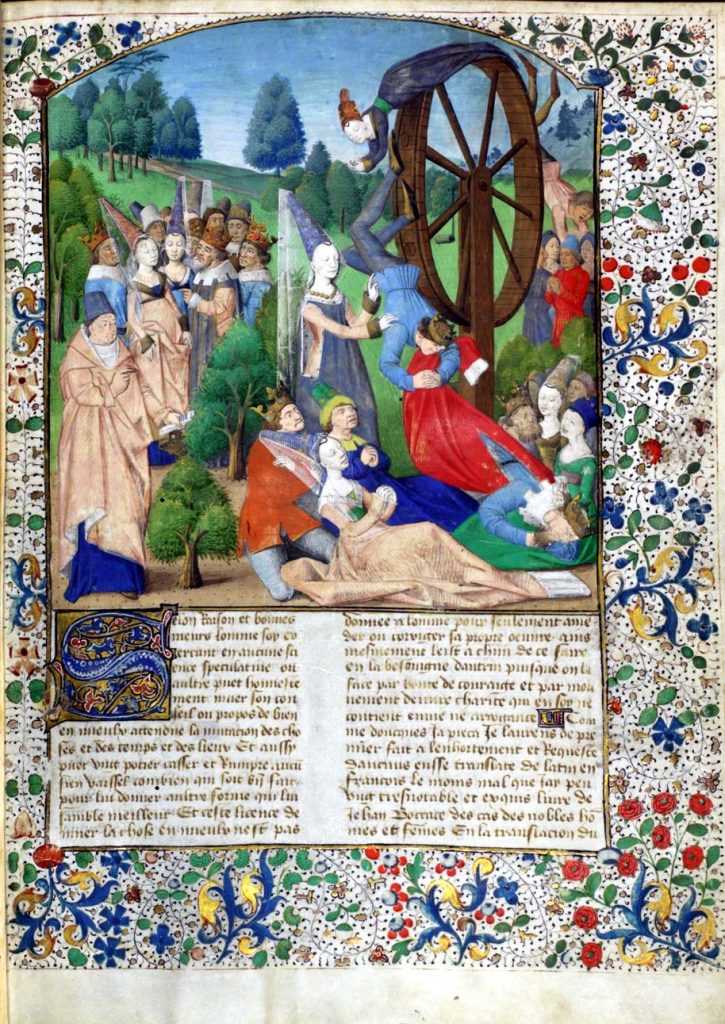

In Act 1, scene 2, lines 31-55 Celia and Rosalind wittily debate the relative power of fortune and nature over human affairs. Fortune was frequently personified in medieval and Elizabethan art and literature, as in the illumination below, taken from a manuscript of the Italian poet Boccaccio’s De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Concerning the Falls of Famous Men, composed 1355–74).

Underlying the verbal fireworks of Celia’s and Rosalind’s exchange is a recognition of the injustice of Rosalind’s disinheritance. Their insight into the human world’s casual injustice is borne out by Duke Frederick’s arbitrary banishment of Rosalind, and by Oliver’s attempts to murder his brother, first in the wrestling match and later in his plan to burn Orlando in his lodging (Act 2, scene 3, lines 23-27).

3. Court Life versus Forest Life versus Country Life

The honest physical realities of life in the forest, captured in Duke Senior’s speech opening Act 2, contrast diametrically with the comforts of urban court life, accompanied as these are by betrayals and injustices. For the court, forest life depends on successful hunts (see above), but the forest is likewise a place for philosophical reflection where moral truths and the goodness of life and nature become obvious, as summed up in the Duke’s famous lines:

And this is our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything. (Act 2, scene 1, lines 15-17)

Orlando’s arrival with the starving Adam causes Duke Senior to moderate his former rosy image of life in general:

Thou seest we are not all alone unhappy.

This wide and universal theatre

Presents more woeful pageants than the scene

Wherein we play in. (Act 2, scene 7, lines 142-145)

A subject that would have interested most of Shakespeare’s audience is Corin and Touchstone’s debate in Act 3, scene 2, lines 11-85 over court versus country (meaning pastoral) life. Corin tries to end the argument by saying, “You have too courtly a wit for me, I’ll rest” (line 67). Touchstone responds rudely by accusing Corin of being ‘shallow’ and a country bumpkin (‘raw’).

Act 3, Scene 2- Touchstone and Corin [3:37 mins]:

- victualled means "had food provided for" ↵

- deflects ↵

- See Thomas McFarland, Shakespeare’s Pastoral Comedy, Chapter 1, "Comedy and Its Pastoral Extension." ↵

- "a tube-shaped glass bead, usually black" (OED) ↵

- bragging, boastful - like a politician or sportsperson who talks about how impressive they are. ↵

- The shepherd Corin acts as their agent for a commercial transaction which any present-day house-buyer will recognise ↵