10 Story

Hamlet is Shakespeare’s longest play, but events are easy to follow and the story is expertly distributed across the five acts. If you would like to begin your study by reading a summary, the best-known prose retelling of Hamlet, retaining many phrases from the play, is in Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare. The Lambs’ collection has been constantly in print since its first publication in 1807, and new editions continue to appear in the 2020s.

Hamlet contains a subsidiary story but, as in Romeo and Juliet, there is no detached subplot. The sub-story of Polonius, Laertes and Ophelia is integrated into the main story of Hamlet’s revenge, and there are obvious parallels between the two families. All the characters, including the Gravediggers who open Act 5 with a grim comedy of their own, are defined by their relationship to the title figure. This complies with the Aristotelian directive for unity of action.[1] If, following most editors, the second quarto is taken as the performance text, the action is not uniformly fast-moving. While time is compressed to within a day or a day and a night in four of the Acts, month-long time lapses occur between Act 1 and 2 and within 4. [2] However, suspense is constant, most scenes are visually entertaining, and peaks in the action are of deadly interest. This is especially true of the climactic sword fight in Act 5. Hamlet’s soliloquies raise questions common to humanity. Dressed in black, he is the chief inhabitant of the shadowy realms of murder and betrayal that underlie the noisy surface of court life in Elsinore. In contrast with some of Shakespeare’s royal courts, for example, the Duke’s forest court in As You Like It, there is no music in Elsinore except for the songs of Ophelia’s madness and music brought by the Players; satire replaces comedy, and most of the puns and verbal jokes are harsh, ironic and full of despair.

‘Why should you read “Hamlet?” by Iseult Gillespie (TEDEd) [5:09 mins]:

Act One

It’s difficult to imagine a more engaging beginning to a story than the Ghost’s manifestation to the sentries and Horatio in Act 1, scene 1, probably first performed on the Elizabethan theatre’s upper stage. The audience is kept wondering about the reason for the midnight materialisation until the climactic Scene 5, when Hamlet confronts the Ghost alone. Speaking then for the first time, the Ghost recounts its murder, reveals who killed it, and imposes on Hamlet the duty of revenge.

Meanwhile, the middle scenes of Act 1 are made tense by the pent-up conflict in the Danish royal family, the military threat posed by the young Norwegian commander Fortinbras, and the Ghost’s anticipated reappearance.

In Scene 1 the watchmen Marcellus and Bernardo are united in their report of ghostly visitations. At first, the audience is encouraged to join Horatio in his scepticism, but doubts are dispelled by the Ghost’s reappearances at the beginning and end of the scene. Meanwhile, in a not-so-subtle exposition, Horatio explains the reason for Elsinore’s military preparedness in the renewed threat from the young Norwegian commander Fortinbras and his army.

Explore the Text

- Retell in your own words Horatio’s story of the conflict between Norway and Denmark (Act 1, scene 1, lines 91-112).

- Relations between male relatives—fathers and sons, uncles and nephews- are central to Hamlet. Three fathers are slain, and three sons are tasked with avenging them. How has Fortinbras responded to the killing of his father?

- What further loss does Fortinbras hope to redeem by attacking Denmark (lines 112-116)?

Scenes 2 and 3 in Act 1 encourage the audience to contrast the dynamics within two families: Claudius (the newly-crowned king), Queen Gertrude, and her son Hamlet in scene 2, versus Polonius the king’s counsellor, his son Laertes and his daughter Ophelia in scene 3.

Long speeches by Claudius dominate scene 2, as he deals with a list of events and issues:

- he mourns his dead brother and confirms his marriage to his widowed sister-in-law Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother

- he dispatches Cornelius and Voltemand to warn the ailing king of Norway to restrain his nephew Fortinbras;

- he permits Laertes to return to his studies in Paris;

- by naming Hamlet as his heir, he attempts to reconcile Hamlet with his reign and his marriage to Gertrude.

To see some modern versions of Hamlet follow these links: David Tennant as Hamlet in Gregory Doran’s 2008 production for RSC and Pappa Essiedu in 2018 as Hamlet for RSC. In these images, Hamlet is young, following Shakespeare’s original conception.

Hamlet, in black, is isolated in this public scene by his opposition to Claudius, which he expresses in asides and cryptic responses. Glittering in their court dress and absorbed in their new relationship, the newly-weds Claudius and Gertrude hear what Hamlet says, but don’t listen. Hamlet’s distrust, anger and unhappiness are obvious to the audience, but Claudius and Gertrude are satisfied when he agrees not to return to his studies in Wittenberg. Note, however, that Hamlet consents to his mother’s plea, not to Claudius: ‘I shall in all my best obey you, Madam’ (Act 1, scene 2, line 124).

Claudius goes away to celebrate with rounds of drinking interspersed with cannon fire, a custom that Hamlet later judges to be ‘more honoured in the breach than the observance’ (Act 1, scene 4, lines 17-18).[3] In scene 2 Claudius’ approaches to foreign policy and family matters are sensible, but the audience will soon discover that his reign is fatally flawed by murder and hypocrisy.

First Soliloquy: Act 1, scene 2, Lines 129-159

The departure of Claudius and his entourage leaves space for the first of Hamlet’s six soliloquys. The opening eight lines universalise his despair: ‘How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable / Seem to me all the uses of this world!’ (lines 137-38). In the remainder, he explains the specifics—grief for his father, whom he idealises as an excellent king and loving husband, and his mother’s remarriage within a month to his father’s brother.

Explore the Text

- What image of Denmark does Hamlet’s garden metaphor (lines 139-141) conjure up?

- In classical mythology, who was Hyperion? What was a satyr? What is Niobe’s story? What labours did Hercules accomplish?

- What (if any) value can you find in these associations, which would have been understood into the twentieth century by many audience members, but which present-day audiences usually have to research?

Hamlet’s affectionate, relaxed greeting to Horatio, Marcellus and Barnardo, which follows in scene 2, contrasts with the repressed tension in his few words to Claudius and the cosmic agony of his soliloquy.

Dramatic pattern: This sequence, of Hamlet’s accustomed state of tension and heartbreak over betrayals by those closest to him, interrupted by trustful conversations with Horatio and minor figures such as the Players and the Gravediggers recurs throughout the play.

Hamlet’s special friendship for Horatio gradually emerges as the only stable point in the shifting sands of Hamlet’s relationships. Scene 2 ends with his agreement to join Horatio and his friends in their planned night vigil for the Ghost.

Scene 3 reveals the masculinist orientation of Hamlet, as Ophelia’s brother Laertes and her father Polonius lecture her separately on the dangers that they think Hamlet’s courtship poses. Watch the video below for a picturesque but shortened enactment of this scene, which reveals the differing weaknesses of these three characters (analysed in the next chapter, ‘Characters’).

To Thine Own Self Be True- Hamlet [2:43 mins]:

In Scene 4, the Ghost reappears. Hamlet’s address and questioning (lines 43-62) capture the otherworldliness—the total exceptionality—of what is happening, as well as the terrifying, carnal nature of the Ghost:

What may this mean,

That thou, dead corse, again in complete steel

Revist’st thus the glimpses of the moon,

Making night hideous and we fools of nature? (lines 56-59)

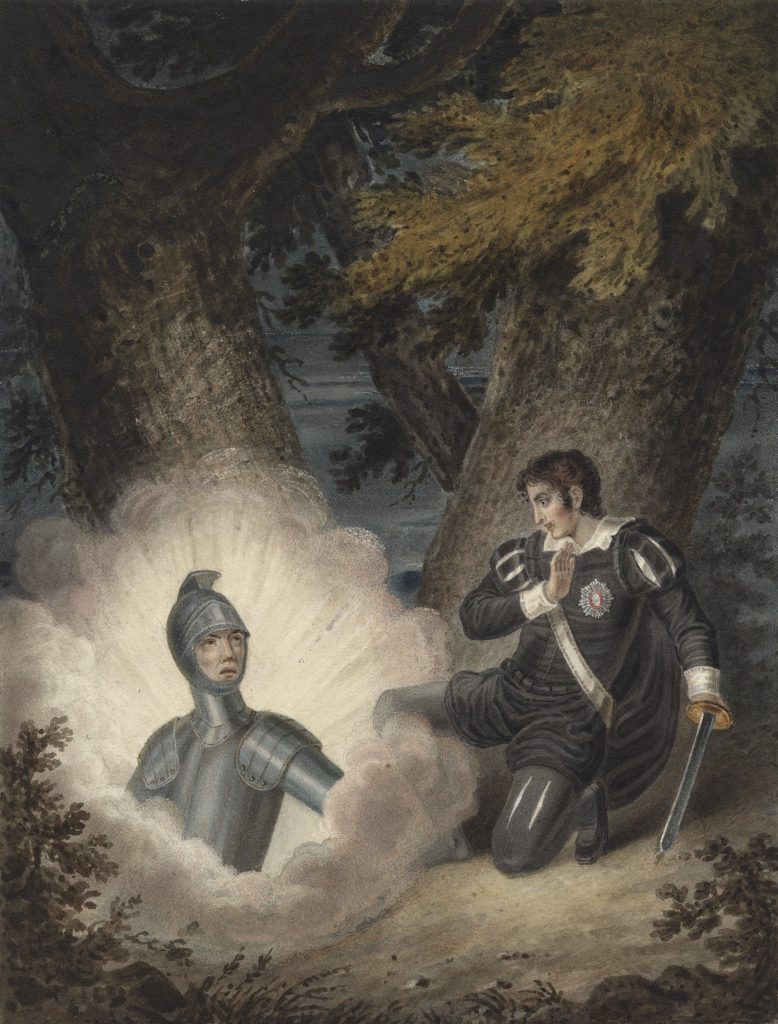

These qualities are not apparent in the following illustration of Hamlet’s encounter with the Ghost:

The Ghost is an Elizabethan foreshadowing of otherworldly horror movies in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. For a lively comparative discussion, with images, of the Ghost in Hamlet films, I recommend this article. Hamlet’s determination to follow the Ghost and hear its message is the audience’s first acquaintance with his physical and mental courage. His friends, who, after failing to hold him back decide to follow and protect him, are equally brave.

In scene 5 the Ghost tells the story of its unprepared-for death and imposes on Hamlet the duty of revenge.

Explore the Text

Hamlet’s father died with his sins unforgiven. His murder while sleeping means that he has not been allowed a second in which to repent.

The Ghost’s evocation of its consequent sufferings in Purgatory (where saved but sinning souls were believed to be imprisoned for purification after death) is horrific, but they are more than matched by medieval paintings of this state (Google ‘Purgatory Images’). As often in modern horror movies, the audience is encouraged to fill in any gaps with their imaginations.

1. How does the Ghost’s unfolded tale in Act 1, scene 5, lines 10-22 evoke an image of indescribable suffering?

2. What single metaphor for Purgatory does it deploy? (line 19)

3. How does the Ghost say Hamlet would respond if it provided more details? (lines 20-28)

4. Why has the Ghost manifested to Hamlet? What does it want from him?

5. What metaphors and epithets does the Ghost apply to Claudius?

6. What deadly sins does the Ghost say Claudius and Gertrude have committed by their marriage? (lines 49-90)

Hamlet agrees to carry out the Ghost’s demand for revenge even before it tells its story:

Haste me to know ‘t, that I, wish with wings as swift

As meditation or the thoughts of love,

May sweep to my revenge. (lines 35-37)

After the Ghost vanishes, however, Hamlet is more alone than ever. He is disconnected from his friends, whom he feels he must swear to secrecy. His jokes about the Ghost’s interjections during his friends’ oath-taking are a defence, hysterical if you like, against the chilling horror of his dead father’s reappearances.

Act Two

In Act 2 the pace of the story slows and ideas and characterisation are hugely enriched. Like a hard-fought game of Magic or chess, the act consists of moves by Hamlet’s enemies and counter moves by himself. Through all the half-truths, uncertainties and revelations, Polonius buzzes on- and off-stage like a demented mosquito.

In Act 2, scene 1:

Polonius sends his servant Reynaldo to spy on Laertes, who is living in Paris. Reynaldo sensibly observes that secretly questioning Laertes’ friends about his doings—‘as gaming … drinking, fencing, swearing, / Quarrelling, drabbing’ (lines 27-30),—would dishonour him, but in a typically slippery move, Polonius retorts: ‘That’s not my meaning’ (line 34). As far as his dependent position allows, Reynaldo expresses contempt for Polonius, for example in their closing exchange:

POLONIUS:… You have [understood] me, have you not?

REYANALDO: My lord, I have. (lines 75-76)

Explore the Text

Experiment with different ways of delivering Reynaldo’s line (76).

What signs are there in the closing scenes of Scene 1 (77-82) that Reynaldo has had enough, and wants to get away from Polonius?

In Act 2, scene 2:

Claudius’s plots are conceived and carried out:

- King Claudius and Queen Gertrude arrange for the sycophantic Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on Hamlet.

- After interrogating his daughter, Polonius tries at tedious length to persuade the King and Queen that Hamlet truly is mad, and that ‘the cause of his defect’ is his thwarted love for Ophelia (Scene 2, lines 92-160).

- However, Claudius and Gertrude want more proof (Scene 2, lines 161-182). Polonius accordingly agrees to set Ophelia to converse with Hamlet while he and Claudius spy on them.[4]

- In conversation with Hamlet, Polonius puts his ‘madness’ theory to the test.

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s subtler approach collapses when they admit that they are in Denmark because Claudius sent for them.

Hamlet’s counter-plot commenced:

Heralded by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the arrival of the players is the turning point of scene 2. At line 445 Hamlet’s combative stance, his ‘madness,’ transforms into an enthusiastic welcome to his ‘old friend,’ the First Player, and his company. They agree that the actors will perform ‘The Murder of Gonzago,’ with an insert by Hamlet included, to entertain the court the next evening (lines 561-570). The closing lines of Hamlet’s soliloquy ending Act 2 reveal his counter-plot:

the play’s the thing

Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king. (lines 633-634)

Hamlet’s Conversations in Scene 2

Conversation with Polonius: Act 2, scene 2, lines 187-237

Hamlet insults Polonius during their exchange. Polonius indicates to the audience that he is struggling to keep up. Hamlet shows the audience what he is truly feeling; and not only about Polonius.

Hamlet with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: Act 2, scene 2, lines 240-391

This conversation moves from the frankness of genuine friendship (lines 240-254) to the arousal of Hamlet’s suspicion about the reasons for the pair’s sudden arrival, expressed in line 258, to a demand, made ironically ‘in the beaten way of friendship,’ that they sincerely reveal why they have come to Elsinore (lines 289-291). The turning point is the admission that Hamlet wrings from Guildenstern. ‘My lord, we were sent for’ (line 315). It’s not spelled out, but all three understand this line to mean that Claudius has sent for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on Hamlet. Hamlet responds to Guildenstern’s spark of honesty with a description from the inside of depression (lines 318-332), a condition that the fascinated Elizabethans diagnosed as stemming from an excess in the body of ‘black bile,’ and wrote about at length as ‘melancholy.’ Hamlet describes the compelling beauty of the universe that humans inhabit, the earth’s ‘goodly frame’; the air’s ‘most excellent canopy’; and ‘this brave o’erhanging firmament … fretted with golden fire,’ meaning the earth’s outermost sphere, decked with stars. But to him all this magnificence seems like a ‘foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.’ Humans likewise, with all their gifts and powers, appear to him as a ‘quintessence of dust.’ Visit the RSC’s website to view a modern depiction of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Hamlet’s thwarting in Act 2 of the manoeuvres against him is a game that audiences are encouraged to enjoy. Disguised by his ‘madness’ he is able to ridicule his opponents, all of whom—Polonius, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern—are Claudius’ puppets. Unsure how to respond, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are never totally convinced that Hamlet is mad. And, as Hamlet warns his friends in Act 1, his madness is a strategy, a weapon that he wields to unmask and punish his enemies.

In contrast with his rebuttals of Claudius’ human parasites, Hamlet’s welcome to the Players, individually and as a group, is warm and genuine. All signs of madness disappear. When Polonius disparages the Players he counter-attacks, crediting them with being ‘the abstract and brief chronicles of the time’ (lines 550-551).

Hamlet’s and the First Player’s recitation

The dramatic speeches recited in turn by Hamlet and the First Player have no known direct source. They are probably Shakespeare’s invention, mediated from Vergil’s The Aeneid through Christopher Marlowe’s play, Dido Queen of Carthage (1594). The death of Priam, king of Troy, is narrated in iambic pentameters.[5]. Typical of earlier plays, their regularity contrasts with Hamlet’s flexible verse. The outdated vocabulary—‘impasted,’ ‘forged for proof eterne,’ ‘bisson rheum,’ ‘made milch’—is likewise atypical of Hamlet. After fifteen lines, Hamlet invites the First Player to continue the recitation. A Homeric simile (lines 508-517) culminating in a half-line—‘Now falls on Priam’ (line 516)—marks the climax, which is Priam’s death. Polonius is utterly unmoved by the performance, a response that draws an insult from Hamlet—‘he’s for a jig or a tale of bawdry or he sleeps’ (lines 525-526); and the Player proceeds to describe the desperation of Priam’s queen, Hecuba.

The recitation references the situation in the outer play:

- It narrates the murder of a king.

- The murderer, Pyrrhus, is a figure of terror.

- The emphasis, in this passage and others, on the bloody horror of the deed, is atypical of Shakespeare’s mature writing.

- The blame for Troy’s tragic fall is laid on the ‘strumpet’ Fortune (lines 518-522, 535).

- Hecuba’s frantic grief contrasts with Gertrude’s recovery and remarriage after King Hamlet’s death.

Hamlet’s closing soliloquy: Act 2: scene 2, lines 576-634

Hamlet’s reflection moves from self-reproach at what he fears may be his lack of courage in taking prompt revenge, to exposition, beginning at line 617, of his plan to test Claudius’s guilt by staging a reenactment of his father’s murder.

Act Three

Act 3 is a turning point in Hamlet. It contains three major events:

- Hamlet confirms Ophelia’s disloyalty.

- Claudius’ reaction to the play-within-the-play confirms his guilt.

- Hamlet kills Polonius in mistake for Claudius.

Scene 1 opens with a meeting between the King and Queen and their three henchmen. Ophelia is a mostly silent presence. Not wanting to reveal that they have admitted to Hamlet that they are Claudius’ spies, Rosencrantz reverses the truth by saying that Hamlet asked few questions of them, but freely answered questions that they put to him (lines 14-15). Aided by Polonius, the pair persuade Claudius that Hamlet’s promotion of the play is a sign that his ‘madness’ is abating. Gertrude still believes that Hamlet’s attraction to Ophelia is its cause. She hopes that Ophelia’s virtues will bring about Hamlet’s cure and an honourable outcome for them both (lines 42-47). Polonius then stage-manages Ophelia to stroll with a prayer book and goes into hiding with Claudius. Hamlet enters and speaks his most famous soliloquy.

Hamlet’s soliloquy: Act 3, scene 1, lines 64-96

These are some of the best-known lines in English.

Watch Paapa Essiedu as Hamlet performing the famous ‘To be or not to be’ speech by RSC [3:24 mins]:

Explore the Text

- Watch the performance of the ‘To be or not to be’ speech.

- What assessment of human lived experience do these lines offer?

- What conclusion does Hamlet therefore reach? (lines 71-72)

- What objection to this conclusion immediately occurs to him? (lines 73-77)

- What evaluation of human life, based on a list of common experiences, follows? (lines 79-85)

- So why do most people not choose to end their lives? (lines 86-96)

What Hamlet sees as his worst betrayal—by Ophelia—follows immediately.

- He greets her unexpected appearance with a loving wish that she will pray for him.

- She responds by returning Hamlet’s love-gifts, as her father ordered.

- Wounded, he denies having given her anything.

- Wounded in her turn, she accuses him of unkindness.

At this point (line 113) most productions indicate that Hamlet becomes aware of the hidden listeners Claudius and Polonius. His attitude hardens, and he directs a stream of insults at Ophelia:

- She is dishonest.

- Her beauty is merely a bawd[6] for her dishonesty.

- She should never have believed him when he said he loved her. Desire for a beautiful woman will turn any man into a liar.

- She should enter a nunnery and so avoid breeding sinners like himself.[7]

- Enraged by another lie, that her father is ‘at home,’ Hamlet upbraids her: women make monsters of men, so wise men will avoid them. False, they paint their faces, adopt winning ways, and pretend to be innocent. He will have no more of this: married people, except for one, will live, but the unmarried (Ophelia and himself) will stay as they are.

Explore the text

When Hamlet says that one married person will not live, he is talking about ________.

Again and again, Hamlet exposes humans’ tragic failure to understand one another; Ophelia’s, Claudius’ and Polonius’ reactions to the interchange between Ophelia and Hamlet are an example:

- Ophelia concludes that Hamlet is indeed mad (wrong!).

- Claudius decides that Hamlet doesn’t love Ophelia (wrong!); a speedy voyage to England might restore Hamlet to himself;

- Polonius stays with his view that ‘neglected love’ of Ophelia is the cause of Hamlet’s ‘grief.’ (King Hamlet’s murder is the main cause.)

Scene 2 builds slowly to the climax of Act 3, which is a massed event, ending in Claudius’ flight from the enactment of his fratricide in ‘The Murder of Gonzago’ (renamed by Hamlet mid-performance, line 261, as ‘The Mousetrap’).

- Hamlet instructs the Players, who leave the stage to prepare.

- Polonius, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern exit to fetch the King and Queen.

- Dismayed by the betrayals of his family and their flatterers, Hamlet praises Horatio for his loyal friendship and Stoic indifference to Fortune’s fickleness.

- Hamlet’s bitter exchanges with the onstage audience—Claudius, Polonius, Gertrude and Ophelia—build tension. He lies at Ophelia’s feet to watch the play.

- The dumb-show is a silent miming that matches the Ghost’s account of its murder. The dead king’s queen accepts the murderer’s love offerings.

- In the spoken play-within-the-play, ‘some dozen or sixteen’ lines of which are an insert by Hamlet (Act 2, scene 2, lines 566-70), the Player Queen professes loyalty to her husband. She vows that if he were to die, she would remain a widow. He falls asleep and she leaves. The stage murderer, the Player King’s nephew Lucianus, pours a ‘mixture rank, of midnight weeds collected’ (line 283) into the King’s ear.

Explore the Text

- During breaks in the performance, Hamlet accuses Gertrude and (more often) Ophelia of disloyalty. Find some examples. How fair are Hamlet’s accusations?

- How does Claudius finally react to the play?

- How does Hamlet react to Claudius’ flight?

Scene 2 ends when Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, followed by Polonius, deliver Gertrude’s message that Hamlet should visit her in her closet (private chamber). Hamlet’s replies are witty, evasive and aggressive. For example, borrowing a recorder from a Player-musician, he offers it to Guildenstern. When, embarrassed, Guildenstern admits that he has not the skill to play it, Hamlet drives home Guildenstern’s betrayal of their friendship:

Why, look you now, how unworthy a thing you make of me!

You would play upon me, you would seem to know my stops,

you would pluck out the heart of my mystery,

you would sound me from my lowest note to the top of my compass;

and there is much music, excellent voice in this little organ,

yet you cannot make it speak.

‘Sblood, do you think I am easier to be played on than a pipe?

Call me what instrument you will,

though you can fret me, you cannot play upon me. (lines 393-402)

Explore the Text

- Trace the weaving of musical metaphors through this speech, e.g. consider the double meaning of ‘fret’ (line 402).

- How do we know that Hamlet is becoming angrier as he speaks?

Act 3, scene 3 opens with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern at their worst, fawning to Claudius, who commissions them to escort Hamlet to England. Polonius, likewise at his worst, adds his quota to the flattery—‘as you [Claudius] said (and wisely was it said)’ (line 33). Polonius plans to eavesdrop on Hamlet’s conversation with his mother and report back (lines 29-38). Now at his most cowardly, Claudius tries to pray for forgiveness, but realises that repentance without the surrender of his gains would be meaningless and that divine justice, which cannot be misled, is certain to be delivered to him after death.

At the end of Scene 3, Hamlet restrains himself from exacting revenge while Claudius is praying. Instead, he plans to kill him amidst his sins, so that ‘his soul may be as damned and black / As hell, whereto it goes.’ (Act 3, scene 3, lines 99-100)

- Is Hamlet at his worst in this line of thought?

- What excuses, if any, can you find for the behaviour in scene 3 of each of these four characters?

Scene 4, the second climax in Act 3, speeds up the family tragedy. Hamlet slays Polonius in mistake for Claudius, upbraids and instructs his mother, and responds to a visitation by the Ghost, whom Gertrude cannot see or hear. Watch the scene as excerpted from the Branagh movie here:

Polonius’s Death [1:55 mins]:

The encounter with his mother ends when Hamlet ‘lugs the guts[8]into the neighbour room’ (line 235). The text is unclear, and stage directions inserted by editors disagree, as to whether Polonius’ body is visible to the actors and/or audience during the conversation that follows between Hamlet and his mother. Distressed by Polonius’ sudden death, Hamlet drops his sarcastic pose and mercilessly accuses his mother, who (unbelievably?) has not realized that her lightning-fast remarriage has distressed her son:

What have I done, that thou dar’st wag thy tongue

In noise so rude against me? (lines 47-48)

In response, Hamlet becomes a fiery preacher:

- His mother’s action in marrying Claudius was immodest.

- It violated her marriage vows.

- It made a mockery of religion.

- It offended heaven itself.

- He compares pictures of the two kings, pointing out that Claudius’ is less handsome and less accomplished.

- How could Gertrude, whose mature age should have made her wise, have chosen Claudius over King Hamlet? Was she deceived by the devil?

Hamlet’s eloquence brings Gertrude to a full realisation of her guilt:

O Hamlet, speak no more.

Thou turn’st mine eyes into my very soul;

And there I see such black and grainèd spots

As will not leave their tinct [i.e., never cease to be visible]. (lines 99-102)

The Ghost reappears to hasten Hamlet in his revenge while urging him again to care for Gertrude: ‘Conceit in weakest bodies strongest works’ (line 130), i.e., their weak bodies make women over-imaginative. After the Ghost leaves, Hamlet advises his mother to abandon sleeping with Claudius. Using the terms of a sermon, ‘master the devil, or throw him out,’ he describes the disgusting physical touchings from Claudius that Gertrude must rebuff. She must also conceal Hamlet’s sanity and his schemes from Claudius:

Not this by no means that I bid you do:

Let the bloat king tempt you again to bed,

Pinch wanton on your cheek, call you his mouse,

And let him, for a pair of reechy kisses

Or paddling in your neck with his damned fingers,

Make you to ravel all this matter out

That I essentially am not in madness,

But mad in craft. (lines 203-210)

Explore the Text

How ‘normal’ do you judge Hamlet’s sexual specificity in these lines to be, given that he is an adult son?

Act Four

Events move swiftly through three early scenes. Gertrude demonstrates loyalty to Hamlet by agreeing when Claudius states that Hamlet is mad.[9] Claudius sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to find out where Hamlet has hidden Polonius’ body. They fail, but, arrested and brought to Claudius, Hamlet reveals that ‘you shall nose him as you go up the stairs into the lobby’ (scene 3, lines 40-41). In scenes 2 and 3 ‘mad’ Hamlet’s truth-telling to Claudius and his accomplices is caustic.

Left alone, Claudius tells the audience that he is sending letters to the King of England ordering Hamlet’s execution. Outside Elsinore in scene 4, and guarded before his embarkation by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Hamlet encounters the Norwegian army marching to make war on Poland. Hamlet regrets in a soliloquy (lines 34-69) that he has not followed Fortinbras’s warlike example in his pursuit of revenge.

He resolves:

O, from this time forth

My thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth! (lines 68-69)

We next hear about Hamlet in scene 6, when Sailors deliver to Horatio a letter narrating his capture at sea by pirates. The Sailors will bring Horatio to Hamlet, where presumably a ransom will be paid for his release. The remaining scenes in Act 4 (scenes 5-7) enact family happenings in Elsinore following Hamlet’s departure. They focus on Ophelia and Laertes in their dealings with Gertrude and Claudius.

In scene 5, Gertrude hesitates to grant Ophelia an audience. Her motives are a mixture of fear and repentance:

To my sick soul (as sin’s true nature is),

Each toy seems prologue to some great amiss.

So full of artless jealousy is guilt,

It spills itself in fearing to be spilt. (lines 22-25)

Ophelia’s mad display on entering appalls Gertrude and Claudius, and no doubt also the audience. When Ophelia was last on stage during the performance of ‘The Mousetrap’ she fended off Hamlet’s verbal attacks. Now her songs and utterances lament her inconsolable grief: the man she loves has killed her father. From this, there can be no recovery or healing.[10]

Explore the Text

- Find a song in Act 4, scene 5 where Ophelia mourns her father’s death.

- Find songs in which she grieves for the loss of Hamlet’s love.

- Kenneth Branagh’s movie contains a scene in which, on happier days, Hamlet and Ophelia make love. Such a scene could not have been staged at Shakespeare’s Globe. Based on Ophelia’s second song, the sexual language of which would have shocked early audiences, how justified do you think Branagh was in adding the sex scene?

- ‘Since the notion of women’s oppression was excluded from the consciousness and language of Elizabethans, Ophelia can protest her subjection only when she is mad.’ Discuss.

After Ophelia, attended by Horatio, leaves the stage, Claudius laments his woes while also bringing the audience up to date (lines 80-103):

- He blames Ophelia’s madness solely on grief for Polonius.[11]

- Hamlet’s violence has led to his deportation.

- Danes are restless because Polonius has disappeared. Claudius and Gertrude have buried him in secret.

- Ophelia is ‘divided from herself and her fair judgment.’

- Laertes has arrived secretly from France; the people have aroused his suspicions about Polonius’s murder and are calling on him to become king in Claudius’ place.

That is Laertes’ cue to burst in on Claudius and Gertrude, while his cohort of rebel Danish soldiers remains outside. In contrast with Hamlet, Laertes demands instant revenge for his father’s death. From Laertes’ arrival to the end of the play, Claudius acts as an astute manipulator, comparable in treachery (though not in glamour) with Shakespeare’s Richard III. His first ploy is to confront Laertes’ threat with a show of courage that is steeped in hypocrisy:

Let him go, Gertrude. Do not fear our person.

There’s such a divinity doth hedge a king

That treason can but peep to what it would,

Acts little of its will…. (Act 4, scene 5, lines 137-40)

Explore the Text

Claudius murdered his brother to become king, so explain some of the ironies in these lines.

Claudius’ second move is to swear to Laertes that he is innocent of Polonius’s death and that, given an opportunity, he will prove it. At this point, Ophelia enters, and Laertes realises that his father’s death is compounded by his sister’s madness. Yet he points out that her words, apparently nonsense, are full of truth. This applies to the flowers that Ophelia distributes, and, it is implied, resembles. Their symbolism is still debated by editors and critics; broadly it is as follows:

- Rosemary for remembrance and pansies (from French pensées) for thoughts: Ophelia asks Laertes to remember her.

- Fennel for flattery and columbine for unfaithfulness in love: Ophelia probably gives these to Gertrude.

- Rue (Herb of Grace) for sorrow, regret, repentance, probably given to Claudius. Ophelia claims rue also for herself, but ‘you [Claudius?] may wear your rue with a difference.’

- Daisy stands for deception, applicable to those who, like Hamlet, have abandoned Ophelia or failed to protect her.

- Violets are a symbol for faithfulness; faithfulness withered for Ophelia when Hamlet killed Polonius.

In scene 7, Claudius, who is a consummate tactician, continues his charm assault on Laertes, which presents Hamlet in the worst possible light. Ever the hypocrite, Claudius persuades Laertes that he should take quick revenge for Polonius’ death, since the passing of time ‘qualifies the spark and fire of love,’ and goodness ‘dies in his own too-much [i.e., excess]’ (lines 129-134). Laertes is ready without any urging, ‘To cut [Hamlet’s] throat i’ th’ church’ (line 144). Praising Laertes’ reputation as a consummate swordsman, Claudius tells him that he will arrange a fencing bout between Hamlet and himself, in which he will contrive that Laertes’ foil is unblunted. Laertes tops this with an additional plan to anoint his blade with a poison so potent that the smallest scratch will bring death. Claudius outdoes this yet again with his intention to poison the drink that Hamlet is sure to call for during the match.

Poetic justice descends at once on Laertes when Gertrude enters with the news of Ophelia’s suicide by drowning. This is the climax of Act 4. [Gertrude’s report is quoted in ‘Context.’]

Gertrude’s narrative lists the symbolic flowers and plants that Ophelia was gathering before ‘an envious sliver broke’ and she with her ‘weedy trophies … fell in the weeping brook.’

Ophelia’s Flowers [5:55 mins]:

Act 5

Scene 1

When he was last on stage in Act Four, scene 4, Hamlet decided to follow the warlike example of Fortinbras by pursuing immediate bloody revenge on Claudius. When he emerges in the graveyard in Act 5’s opening scene, his attitude has changed. Never again does he adopt the persona of a madman. Instead, he reverts to his complex true nature as a moral philosopher, lover, and man of action. With hard-won inner strength, he awaits his enemies’ next moves. He will respond to events as they unfold.[12]

If no other writings by Shakespeare survived, Hamlet Act 5 would account for the esteem in which he is held. The Act is distinguished from earlier acts by two comic episodes. Let’s examine events as they happen:

The Gravediggers

The Gravediggers’ dialogue is macabre comedy—think Hallowe’en, The Addams Family, Dracula: Dead and Loving It and The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

It contains:

- ‘Deadly’ humour about class distinctions: Adam must have been a gentleman, because how could he have dug without (heraldic) arms?

- Satire of lawyers and their Latinate hair-splitting: ‘It must be se offendendo … if I drown myself wittingly, it argues an act …’

- Riddles: ‘who builds stronger than a mason, a shipwright, or a carpenter?… say a grave-maker. The houses that he makes last till doomsday….’

The First Gravedigger is singing merrily of his own death and throwing dirt and skulls from a new grave-pit, when Hamlet and Horatio arrive. The situation inspires Hamlet to explore truths of life and death, the law, class distinctions, and above all transience: beauty, vitality, wit, and power are all subject to time.

Explore the Text

- Find Hamlet’s thoughts on each of these topics (life and death etc. in Act 5, scene 1, lines 67-223).

- The Gravediggers, and Horatio and Hamlet when in their company, speak prose; when the funeral cortège arrives with Ophelia’s body, the dialogue switches to verse. Two rhyming couplets by Hamlet (lines 220-223) manage the transition. With which other group of non-noble characters in the play does Hamlet speak prose?

- Read aloud Hamlet’s famous meditation on transience while holding Yorick’s skull (lines 190-202). How do the exclamations, pauses, varying sentence lengths, and rhetorical questions guide the actor’s intonations and gestures?

- What might the switch from Yorick as the addressee to ‘my lady’ as subject (line 200) suggest about Elizabethan gender attitudes?

The arrival of Ophelia’s funeral procession doesn’t change the scene’s subject—the subject is death—but it does briefly transform Hamlet the philosopher into Hamlet the passionate lover.

Ophelia’s funeral

Stepping aside, Hamlet and Horatio overhear Laertes rebuking the officiating priest for the meagreness of Ophelia’s funeral rites. Like her life, Ophelia’s death is adorned with flowers, here symbolic of her youth and maidenhood: the priest refers to her ‘virgin crants’ [garlands] and ‘maiden strewments’ [scattered flowers] (lines 240-241). Laertes rebukes the priest by wishing: ‘And from her fair and unpolluted flesh / May violets spring!’ (lines 249-50); scattering flowers, Gertrude laments: ‘I thought thy bride-bed to have decked, sweet maid, / And not to have strewed thy grave’ (lines 256-57).

Laertes expresses his sorrow by leaping into the grave, followed by Hamlet, whose grief and love, he claims, is greater. Their duel begins as a competition in imagery, but quickly becomes a physical struggle, in which Hamlet at first shows a limited restraint: ‘I prithee take thy fingers from my throat’ (line 274). After the enraged fighters are separated, the battle in metaphors resumes, with Hamlet, still beside himself, outdoing Laertes in professions of love. He reshapes Laertes’ extravagant offers—‘Be buried quick with her and so will I’ (line 296) and classical imagery—‘Make Ossa like a wart’ (line 300). Unaware of Claudius’ manipulations, Hamlet is at a loss to understand Laertes’ enmity, finally dismissing it as a mixture of human unreason and stubbornness.

Explore the Text

A puzzle:

Though it was a case of mistaken identity, in Act 3 Hamlet killed Laertes’ father Polonius. Why doesn’t it therefore occur to Hamlet that, as much as from Ophelia’s, Laertes’ rage in this late scene might stem from Polonius’ death? This may be an error in Shakespeare’s allocation of motives. What is your view?

Scene 2

The last scene of Hamlet slowly builds tension to a climax in which the four leading characters die. A brief unsatisfactory resolution completes the play.

Explore the Text

Below is a summary of Act 5, scene 2. Characters are identified by their roles or ranks—’prince’, ‘challenger’ etc. Read through the summary, substituting the correct characters’ names for their roles.

At the opening of Scene 2, a prince converses calmly with a friend about recent events. A comic messenger arrives with a challenge to a sporting fencing match. Fatalistically, the prince accepts. An onstage audience, consisting of a king, a queen and their courtiers, then fills the edges of the stage. The prince apologises to the challenger and asks him to put aside their enmity. The theatre audience knows from an earlier conversation that the challenger’s foil is lethal—poisoned and unblunted. The match seems friendly, and the prince scores a hit. The king celebrates by adding what he says is a pearl (but it is poison), to the cup set aside for the prince. The prince scores another hit and the queen celebrates by toasting her son from the poisoned cup. Conscience-stricken, the challenger hangs back. The next bout is inconclusive, but in the next the challenger, enraged, wounds the prince with the poisoned foil. In struggling they exchange weapons and the prince wounds the challenger. The queen dies. The challenger reveals that the prince has been poisoned and will also die. The prince wounds the king with the poisoned foil and forces him to drink from the poisoned cup. The king dies. The challenger begs the prince for mutual forgiveness and dies. The prince requests his friend to report to the world what has happened. The friend decides instead to drink from the poisoned cup, but the prince prevents him. The prince dies. The enemy army marches in. The enemy prince commands that the fallen prince be given full military honours.

Scene 2 opens with Hamlet’s account to Horatio of his adventures at sea. This is the last in a sequence of internal stories that, together with the subtle and poetic language, make the dialogue of Hamlet as enthralling as the onstage action:

- In Act 1 the Ghost narrates its murder (scene 5, lines 65-88).

- In Act 2 Hamlet and the First Player take turns in narrating the killing of Priam, king of Troy, by the Greek warrior Pyrrhus (scene 2, lines 475-544).

- In Act 3, the dumb show and ‘The Mousetrap,’ internal dramas, recreate the murder of King Hamlet.

- In Act 4 Hamlet’s letter to Horatio tells of his capture by pirates and says that he has ‘much to tell’ (i.e., watch this space) (scene 6, lines 15-29).

- At the end of Act 4 Gertrude narrates Ophelia’s suicide (scene 7, lines 190-208).

- In Act 5 Hamlet supplies the prequel to his letter to Horatio (no. 4, above) by recounting earlier shipboard events and his capture by pirates (scene 2, lines 1-55).

By substituting his forged letter for Claudius’s command to the king of England that immediately on his arrival, ‘My head should be struck off’ (line 28), Hamlet saved his life and contrived the instant execution upon their arrival of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. They thus take Hamlet’s place as victims of Claudius’ plotting. Hamlet insists that this outcome was designed by heaven and that he did the right thing. He repeats the point later: ‘Why, even in that was heaven ordinant’ (line 54); and when Horatio with a euphemism mildly deplores Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s deaths, he brings their motivation (personal gain) and the difference in class between himself and them into the issue.

A troubling fact: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern did not know that the letter they were bearing to the English king was an order for Hamlet’s execution. Claudius reveals this in an aside addressed only to ‘England’ and the audience.

Scene 2 introduces Osric, who interrupts Hamlet’s and Horatio’s conversation. Claudius later addresses this character as ‘young Osric’ (Act 5, scene 2, line 278), but film actors in the role have tended to be older: Peter Cushing (Olivier, 1948) was thirty-five, and Robin Williams (Branagh, 1996) was forty-five. Osric’s age is of interest because Hamlet leads the audience in the enjoyment of his extravagant dress, over-polite manners, and convoluted language, which he brilliantly parodies. Osric must not appear in this scene as a victim of Hamlet’s satiric humour, a fate from which only impenetrable self-importance can save him.

As the court assembles for the fencing match, Hamlet and Horatio talk about possible outcomes. Responding to Hamlet’s misgivings, Horatio offers to make an excuse that will defer the bout. Hamlet’s response is famous:

Not a whit. We defy augury. There is a

Special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be

now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be

not now, yet it will come. The

readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves

knows, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be. (lines 233-38)

Explore the Text

What does Hamlet mean? Rewrite his thoughts in your own words.

Hamlet is a story of nuanced philosophical and political thinking. Characterisation dramatises the truth of human complexity. All this is temporarily set aside in the climax, the sword fight between Hamlet and Laertes, which leads to the deaths of the four leading characters. The fight, which is theatrical entertainment at its finest, resolves the conflict between Hamlet and Claudius that has dominated the story from Act 1. Tension builds from the first clash of foils, and is not released until Hamlet lies dead. Though not always entirely faithful to the surviving scripts, movies provide enthralling enactments of the fight scene. Olivier’s version sentimentalises Hamlet’s and Gertrude’s relationship and reallocates the closing speeches to accommodate his cutting of the arrival of Fortinbras and the Norwegian army. Watch Branagh’s spectacular choreographing of the duel here.

Explore the Text

1. The catastrophic extinction of the Danish royal family—Hamlet senior, Claudius, Gertrude and Hamlet—leads to the subjection of Denmark to Norway under Fortinbras (Act 5, scene 2, lines 371-372).

Is this in your view ‘a consummation devoutly to be wished,’ or does it deepen the tragedy?

2. As he is dying, Hamlet says to Horatio:

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart,

Absent thee from felicity a while,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story. (Act 5, scene 2, lines 381-384)

- Why does Hamlet want his story to be told? (see lines 370-372)

- What have you learned from Hamlet’s story?

- What worth or value does Hamlet’s story hold for 21st-century people?

- See "The Unities" ↵

- (See Edward P. Vining, ‘Time in the Play of Hamlet’ New York Shakespeare Society, 1886) ↵

- Shakespeare sometimes appeals to his English audiences by disparaging overseas customs ↵

- This scheme doesn’t come to fruition until the first scene of Act 3, so the audience is kept in suspense ↵

- five weak-strong feet to each line ↵

- go-between, procurer ↵

- ‘Nunnery’ was a term for a brothel, so Hamlet implies that Ophelia’s professions of love are as false as a prostitute’s ↵

- That is, Polonius’ dead body ↵

- (In Act 3, scene 4 Hamlet ordered his mother to adopt this subterfuge ↵

- Watch a modern version of this scene from the film Ophelia (2018). ↵

- In Hamlet, as in life, people’s understanding of motives, their own and others', is rarely complete ↵

- Read James Shapiro, 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (London: Faber & Faber, 2005), pp.345-58, for a different view ↵