5 Context

“It is impossible to do justice to its riches and inventiveness, and there is something affecting about the loyalty the play continues to inspire among all generations” (Weis 59).

Great art often inspires great art. Since its first performances in the 1590s, Romeo and Juliet has inspired many famous riffs. The very long list, meticulously traced and discussed by Weiss (2003), includes a symphony by Berlioz (1839), an opera by Gounod (1867), an overture by Tchaikovsky (1880), a ballet by Prokofiev (1936), the musical West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein (1957), and two twenty-first century musicals: Roméo et Juliette by Gérard Presgurvic in 2001, and & Juliet, by Max Martin and David West Read in 2019-23.

Performance History

No records of individual performances of Romeo and Juliet survive from Shakespeare’s time. The first performances for which reliable records exist took place in London, shortly after the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660. From that point Romeo and Juliet underwent myriad transformations, many entailing radical changes to Shakespeare’s script. In 1662 it was acted on alternative evenings as a tragedy and a tragicomedy. On one occasion a slip-up by an actress in the pronunciation of ‘Count’ resulted in great hilarity in the audience (Evans 34). Varied ‘improvements’ were made to Shakespeare’s script by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century adapters, among whom were such well-known writers as Dryden. In 1679 Thomas Otway rewrote Romeo and Juliet with the title, The History and Fall of Caius Marius. This version displaced Shakespeare’s original in English theatres for the next sixty years (Weis 59).

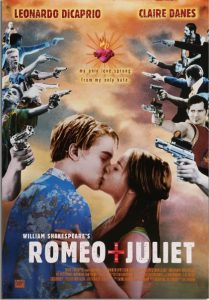

There are two notable film adaptations of Romeo and Juliet, both excellent but very different. They display differing degrees of fidelity to the play that Shakespeare wrote: Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 version in traditional costuming, starring Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting; and Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 adaptation as a modern gangster movie, starring Leonardo di Caprio and Claire Danes: ‘Luhrmann and his writers felt that the chief purpose of their visuals was to illuminate the text’ (Weis 59).

As well as performance, this Pressbook focuses on the words that bear the complex meaning and the heart-moving feeling of Shakespeare’s play. Before you read or watch the play, take a deep breath and clear your mind of any prejudices that you may have about Shakespeare or about romantic love. This play takes teenagers (Juliet is thirteen) and their sexual passions seriously. Juliet’s and Romeo’s mutual love is as deeply joyful as it is tragic.

Reading the Play

You can read the whole of the Second Quarto of Romeo and Juliet (which most editors choose as their base text) here. However, you’ll probably prefer to read it in an edition that follows modern spelling conventions.

Shakespeare’s Sources

The story of Shakespeare’s play was known in Europe from the late 1400s, but the names Romeo and Giulietta, and Montagues and Capulets first appeared in an Italian version in 1535. Further retellings in French, Italian and English followed. Shakespeare knew ‘Rhomeo and Julietta,’ a prose version that William Painter included in his Palace of Pleasure (1566-67). However, his principal direct source was Arthur Brooke’s poem, The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet, published in 1562. In transforming a touching story into a tragic masterpiece, Shakespeare bases his plot and most of his characters on Brooke. For more detail on the sources of Romeo and Juliet, see G. Blakemore Evans’ edition. Regarding Brooke’s poem, Evans states: ‘The miracle is what Shakespeare was able to make of it’ (8). You can read The Tragicall Historye here.

Date of Writing and First Performances

Of the slightly differing dates that each editor proposes for composition, the most recent, by René Weis, is the most convincing. Weis places the writing and first performances between 22 July 1596 and 14 April 1597 (Introduction 34; Evans tentatively concurs 6; Gibbons, 26, says ‘no later than the spring of 1596,’—i.e. no later than May). The performance venues were The Theatre and The Curtain, both north of the Thames in the London suburb of Shoreditch.

Quartos and Folios

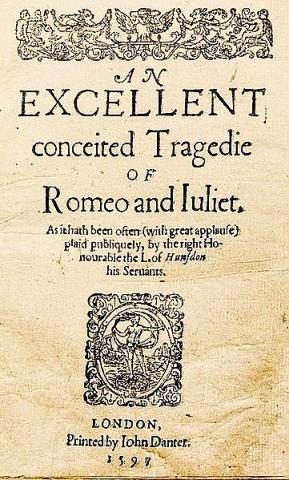

The popularity of Romeo and Juliet with audiences and readers is demonstrated by the frequent printings that accompanied its earliest performances. The First Quarto (Q1, 1597) is a short version probably compiled after plague closed the theatres on 22 July 1596 and drove Shakespeare’s company, the Chamberlain’s Men, to perform in the provinces. Their departure was hastened by the anger of London’s Lord Mayor and council over an offence that Shakespeare or his fellow dramatists had committed (Weis 34).

The printers John Danter and Edward Allde (the second printer, not acknowledged on the title page) wanted people to buy their book. You can see they included pictorial and verbal advertisements on the title page.

In 1594 Shakespeare’s company came under the patronage of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, then the Lord Chamberlain, who was in charge of Queen Elizabeth’s court entertainments. After Carey’s death on 23 July 1596, his son, George Carey, 2nd Baron Hunsdon, became patron, and the company was known briefly as Lord Hunsdon’s Men. When George Carey in turn became Lord Chamberlain on 17 March 1597, the company reverted to its previous name. When King James ascended the throne in 1603 and became the patron the name was changed again, to the King’s Men.

Following the return of the Chamberlain’s Men to London, a longer version of Romeo and Juliet was published. This is known today as the Second Quarto (Q2, 1599). Weiss discusses the differences and overlaps between the two authoritative Quarto texts. Most modern editors have based their text on Q2, while giving differing prominence to Q1’s alternative readings. An example of a significant alternative reading occurs at Act 3, scene 3, line 117, when Romeo is about to kill himself. The stage direction in Q1 states: Nurse snatches the dagger away. Later Quartos and the Folio omit this stage direction, depriving the Nurse of her moment of heroism.

Three more Quarto printings preceded the publication of Romeo and Juliet in the First Folio (1623), a flurry that testifies to the play’s popularity with early readers, and to the speed with which it attained the status of a classic. Most English speakers have heard of, and occasionally refer to Romeo and Juliet, but this doesn’t mean that they have seen it performed or that they have read and understood it.

In 1594 Richard Burbage became the leading actor of the Chamberlain’s Men. Then aged in his late twenties, Burbage is believed to have been the first actor of Romeo.

The boy who first played Juliet may have been Robert Goffe, the likely actor of most of Shakespeare’s early female protagonists (Evans 28). Notes left by accident in Q1 and Q2 confirm that Will Kempe, the well-known clown of the Chamberlain’s Men, put in a cameo performance as the Nurse’s servant Peter and may also have ‘doubled’ as Romeo’s servant Balthazar (Levenson 338).

The Playwright

The 1590s were an intensely creative period, when, in addition to Romeo and Juliet and ten history plays, Shakespeare wrote and helped to stage eight comedies, each of which contributed to a continuing complex exploration of sexual love and romance. The Comedy of Errors, The Taming of the Shrew, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Love’s Labours Lost, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado about Nothing, and As You Like It culminated after the turn of the century in Twelfth Night. While lyrical verse is a principal means of expression in all these plays, of all Shakespeare’s writing for the theatre, Romeo and Juliet has most in common with the sonnets that he composed in the 1590s and early 1600s. Accordingly, this Pressbook pays attention to both the poetic and the dramatic qualities of Romeo and Juliet.

Additional reading

These link to holdings in the James Cook University Library. Please check your own library for these resources.

Olson, Rebecca, et al. Romeo and Juliet. Oregon State University, 2021.

Lehmann, Courtney. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet : A Close Study of the Relationship between Text and Film. Methuen Drama, 2020, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781408166826.

Kellermann, Jonas. Dramaturgies of Love in Romeo and Juliet : Word, Music, and Dance. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2021.

Orgel, Stephen. The Invention of Shakespeare, and Other Essays. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022, https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812298369.