Mabo and Native Title

Overview

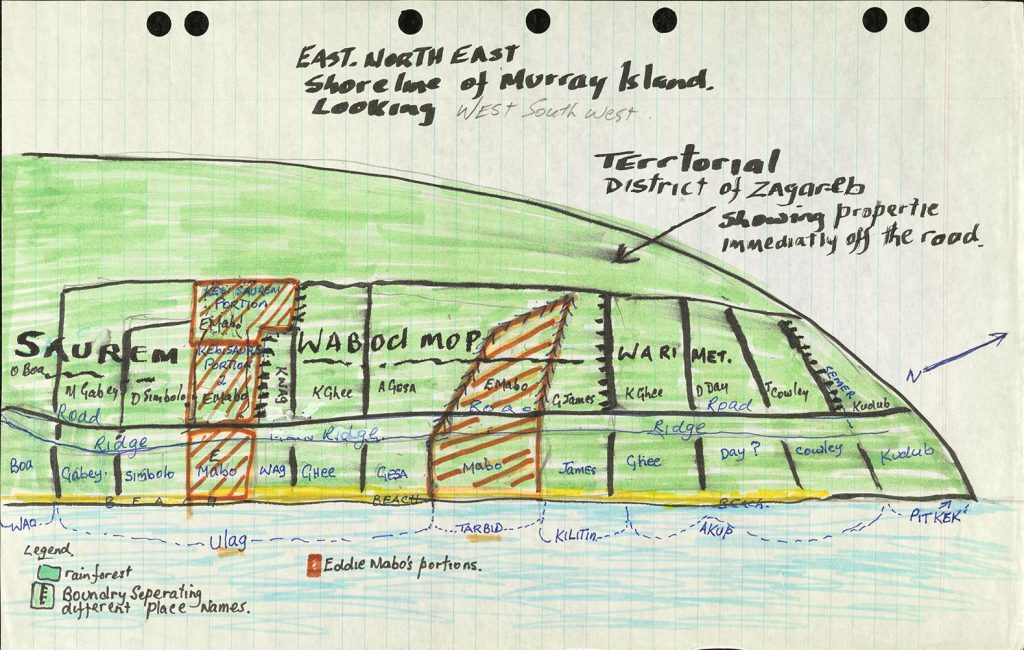

When Koiki discovered his family’s ownership of their traditional lands was not recognised by the government (who considered them “empty” when the colonisers arrived in the lands now known as Australia, and belonging to the Crown), he worked tirelessly to fight against this discriminatory law. Along with fellow plaintiffs Reverend David Passi, Sam Passi, James Rice and Celuia Mapo Salee, he took the State of Queensland to court to argue his case: the lands were not and never had been empty, and belonged to the Traditional Custodians who had been passing the land down through their families for generations. As Koiki was the first named plaintiff, the case became known as the Mabo case.

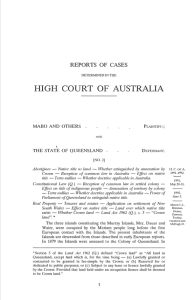

The Mabo case was taken to the High Court, but was briefly adjourned while Mabo and his colleagues fought another legal battle, challenging the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985 (Qld). This Act ensured that no one could lay claim to the islands of Queensland or seek compensation for their annexation. The legal battle to find this Act unconstitutional became known as Mabo v. Queensland (No. 1). The fight to recognise the Traditional Qwners’ rights to the land and overturn the concept of terra nullius (‘void land’) became known as Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2), and it was this latter case that lead to the creation of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

During the time that these cases were progressing through the courts, Koiki was battling cancer and eventually died on 21 January, 1992 at the age of 55. He was convinced of the rightness of their claim and that they would win the court case – and they did – but he did not live to see it. The High Court found in favour of the plaintiffs on 3 June, 1992. The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), which is so strongly connected to the work undertaken by Koiki and his associates, came into force on 1 January, 1994.

Timeline

1981

The decision to initiate the legal case that was to become so well known was made at the Land Rights and the Future of Australian Race Relations Conference, which was held at James Cook University’s Douglas campus in Townsville.

This conference was organised by the Townsville Treaty Committee and the James Cook University Student Union. Loos and Mabo were co-chairs of the Townsville Treaty Committee and joined with the Student Union to plan the conference. The conference brought together Indigenous land custodians, land rights activists, lawyers and historians who participated in and contributed to a packed program. The Aboriginal Treaty Committee, of which the Townsville Treaty Committee was a chapter, had organised a series of conferences and seminars around Australia. The Aboriginal Treaty Committee had been facilitating research that established the paucity of historical research about First Nations occupation and rights to their land. The Townsville Conference further confirmed that it was legal precedent and not history that had underpinned previous court decisions that confirmed the British Sovereignty of Australian land.

The political activism of the James Cook University Student Union can, in a large part, be credited to the Culture and Race Relations course that had been running since 1978. Noel Loos had introduced this course at the Townsville College of Advanced Education, later taken over by the JCU School of Education (Campbell, 1983; McDonald, 1987). The course coordinators invited local activists as guest speakers, including Eddie Mabo. Professor Henry Reynolds has commented that this environment and the student interaction with Koiki that took place helped to foster student activism. The guests they invited to the Townsville Conference brought together the people with the will to change the law and the people who could make it happen.

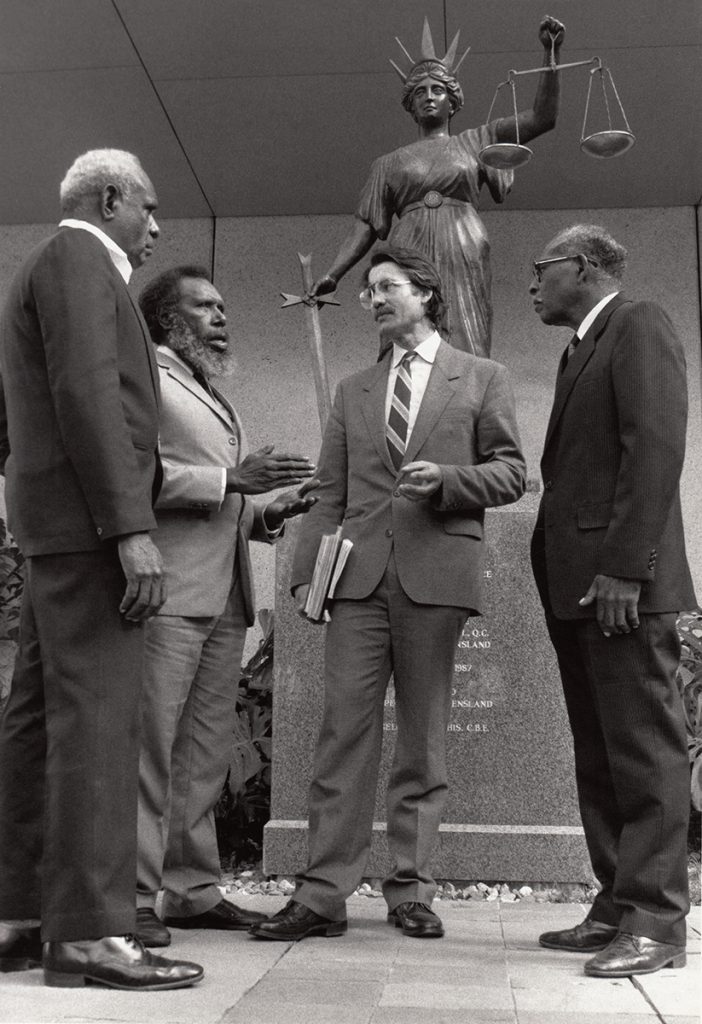

The conference was opened by the mayor of Townsville, Mike Reynolds, and began with a history of white settlement session with presentations by both Henry Reynolds and Noel Loos. The program included many notable speakers, including Mabo himself, who spoke on the Significance of Land Rights for Torres Strait Islanders. Historian, Noni Sharp also spoke on the topic of Islanders and land rights. The man who launched the Aboriginal Treaty Committee in 1979, Dr H.C. “Nugget” Coombs spoke on The Case for a Treaty. Garth Nettheim spoke in several sessions on government policy and possibilities for legal change. Barbara Hocking, a Barrister from Victoria, and Solicitor Greg McIntyre of the Cairns Aboriginal Legal Service, both spoke at the session titled A High Court Test Case. Barbara’s talk, Is Might Right? An Argument for the Recognition of Traditional Aboriginal Title to Land in the Australian Courts, essentially set out a legal framework for the case to come. Greg McIntyre spoke of Aboriginal land rights at Common Law.

The program allowed participants to meet and talk with Koiki and other Mer Island custodians and land rights activists. This resulted in the launch of a case by Eddie Mabo and others with legal backing from Greg McIntyre, Barbara Hocking and Garth Nettheim, and further support from historian Nonie Sharp and Dr Coombs.

May 20, 1982

Having engaged Greg McIntyre from the Cairns Aboriginal Legal Service as their solicitor and Barrister Barbara Hocking soon after the Townsville conference, the legal team was gradually recruited to represent the Meriam plaintiffs. Greg then engaged Ron Castan QC to argue the case for the plaintiffs and Bryan Keon-Cohen was appointed as another junior barrister with Barbara.

Koiki, along with fellow Meriam plaintiffs Celuia Mapo Salee, Reverend David Passi, Sam Passi and James Rice, then launched their land rights case.

October 28, 1982

The video below depicts Eddie Koiki Mabo delivering a guest lecture about the Torres Strait Islander community to education students from the Townsville College of Advanced Education in the Race and Culture course. The video is a digitised version of the lecture released as part of JCU Library’s 50 Treasures: Celebrating 50 Years of JCU project.

1984

Koiki wrote a paper on the music and related history and culture of the Torres Strait for Black Voices, a journal for Australian Aboriginal and Islander peoples, published by the Department of Social and Cultural Studies in Education, James Cook University (Mabo, 1984).

1985

The Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985 (Qld) was introduced. The Act stated that when the Queensland Government became sovereign of the territory in 1879, Torres Strait Islanders lost any claim they had to their land. This legislation, an Act of the Parliament of Queensland, under the political control of Premier Joh Bjelke-Peterson, was aimed to retrospectively abolish the land rights claimed by the Meriam people.

December 8, 1988

The High Court rules in Mabo (No. 1) that the 1985 Act is inconsistent with the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and it is rejected. The case continues, and the plaintiffs are required to prove their traditional land ownership.

January 21, 1992

Koiki dies after a long illness, less than six months before the case is decided. Eddie Koiki Mabo is buried in Townsville on 1 February 1992. His funeral is one of the largest seen in Townsville, with dignitaries and guests attending from all over Australia.

June 3, 1992

History is forever changed in Mabo (No. 2). The High Court rejects the legal doctrine of terra nullius and rules in favour of the Meriam plaintiffs’ ongoing title to their land.

The Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Robert Tickner, said at the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations in Geneva (28th July, 1992) “the process of reconciliation has been formulated to keep faith absolutely with Indigenous peoples’ aspirations and to open up the potential for a substantial evolution in Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations” (Tickner, 1992).

November 22, 1992

Eddie Koiki Mabo, Reverend David Passi, Sam Passi, James Rice, Celuia Mapo Salee and Barbara Hocking are awarded the Australian Human Rights Medal by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

The 1992 Human Rights Medal was awarded to the Murray Islanders who were the plaintiffs before the High Court in the Mabo case. Ms Barbara Hocking was named co-winner of the Human Rights Medal in recognition of her work with the Mabo case and other work she had been involved with to gain legal recognition for Indigenous people’s rights. (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1993, p. 8)

December 10, 1992

Prime Minister Paul Keating attends the Australian launch of the International Year for the World’s Indigenous People at Redfern.

Paul Keating identifies the Mabo decision as recognition of historic injustice against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and says “It begins, I think, with that act of recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing” (Keating, 1992, p. 393).

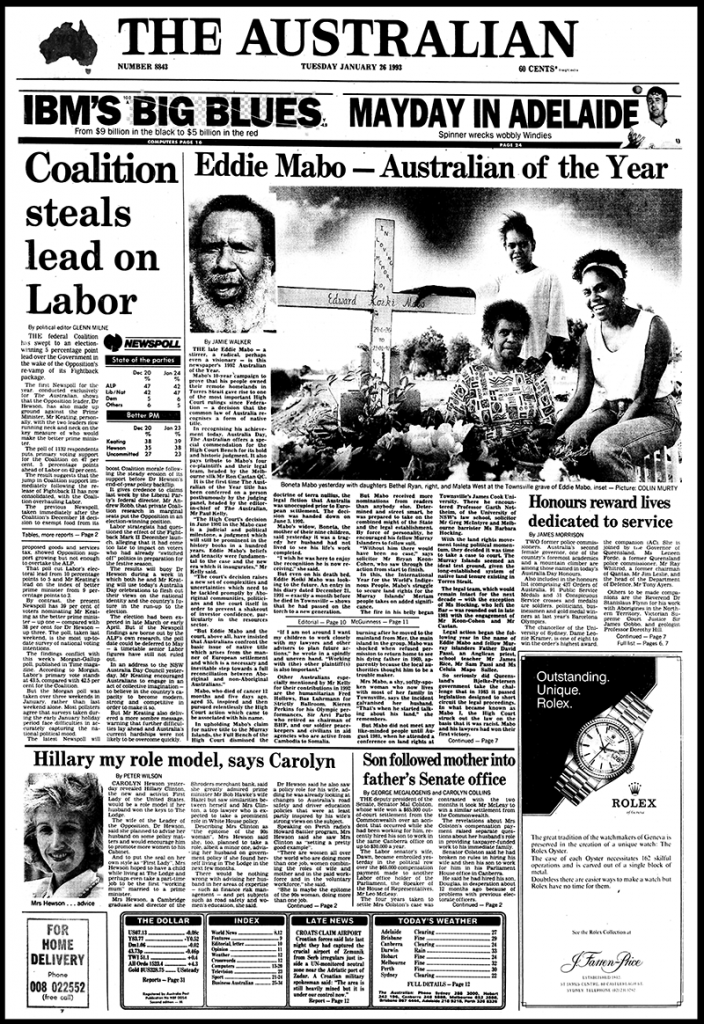

January 26, 1993

The readership of Australia’s national newspaper, The Australian, names Koiki as their “Australian of the Year” in 1992, recognising the significant impact of his life and work.

The reputation and readership of The Australian newspaper was different from current day. The newspaper was widely distributed and read across the country and it was the readership who nominated candidates for the award, with the editor making the final selection. In the same year Mandawuy Yunupingu, educator and lead singer of acclaimed Australian band Yothu Yindi, was the winner of the Australian of the Year award from the National Australia Day Council. Both these men were recognised in a year which was also the United Nations International Year of the World’s Indigenous People.

January 1, 1994

The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) formalises recognition of native title in Australia.

June 3-4, 1995

On the third anniversary of the historic High Court decision, Koiki’s family held a tombstone opening ceremony at his grave site in the Townsville Belgian Gardens cemetery.

Many people travelled from afar to acknowledge the end of the official mourning period, and to honour the man and his achievements. Towards the end of the ceremony, the family revealed a black granite headstone with a representation of a smiling Mabo in bronze. The event is remembered as momentous and culturally significant for many people, including Mabo’s family, friends and members of the community, academics, politicians and 200 Murray Islanders who had travelled down from Mer to participate in the ceremony. Attendees included Anita Keaton, spouse of then Prime Minister Paul Keating. This was the first celebration of Mabo Day.

That night, after the ceremony was over, the tombstone was desecrated by racist vandals. The smiling bronze mask of Mabo’s face was removed and stolen from the headstone and the tombstone was sprayed over with Nazi swastika symbols and racist text in red paint. As at the time of writing, no one has ever been charged for this act of violence and racial vilification.

The headstone was later removed from the grave and taken from the cemetery to avoid further attacks on the grave site. A decision was then made by Koiki’s family to rebury him at Las (his birthplace) on Mer in a traditional burial ceremony.

September 18, 1995

Eddie Koiki Mabo is reburied by his family and community with a traditional ceremony on Mer.

Related Content

Conference held in Townsville, 28-30 August, 1981.

- Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985 (Qld)

- Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

- Mabo v Queensland [1988] HCA 69; (1989) 166 CLR 186 (8 December 1988)

- Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (“Mabo case”) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 (3 June 1992)

- Eddie Mabo’s Tombstone Opening, Trevor Graham

- Report on the vandalism of the Mabo’s grave in the Canberra Times

- Land Rights & the Future of Race Relations Conference Program