Module 5. What project governance comprises

Overview

Project governance plays a role in the successful outcomes of a project (Joslin & Muller, 2016). However, project governance is complex and there is no one-size-fits-all approach that can be applied. Project managers and project teams need to tailor their project governance to their specific needs, including organisational requirements, project needs and legal reporting obligations.

Project governance provides structure and supports the development of objectives of the project, a means to attain these objectives, and how to monitor and control performance (Turner, 2006). Therefore, good project governance ensures that the project objectives are aligned with organisational strategic and operational objectives. To meet these objectives, Turner (2006) states that there are three primary goals of project governance: (1) choosing the right project, (2) delivery of the selected project efficiently and effectively, and (3) ensuring projects undertaken are sustainable and achievable.

A significant factor influencing project governance and what is deemed important is based on the governance style of the organisation that owns and leads the project. Research by Muller et al. (2013) identified the influence the governance style of a parent organisation has on the decisions made within the governance requirements of a project. There are two key themes which are important in project governance – transparency and accountability. First, the work that is completed with internal and external stakeholders must be transparent. Transparency is defined as providing a clear and tangible link between work being completed, the manner in which it is being completed and the project outcomes (Walker et al., 2008). Second, the organisation and project team must be accountable, which links back to transparency of decisions made with stakeholders. The two themes are linked because to have a clear accountability process, transparency is needed. Therefore, project governance mechanisms have the capacity to impact both project transparency and accountability within the project and more broadly (Crawford & Helm, 2009; Osei-Tutu et al., 2010). Finally, project governance helps define the relationships between the stakeholders (both internal and external), specifically documenting who are directly and indirectly involved within the project and the outcomes.

Let’s look at what good project governance entails.

Good project governance

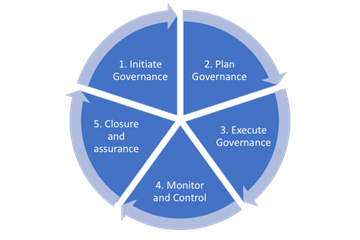

Good project governance requires the establishment of projects and organisational processes that meet the needs and minimum standards of the parent organisation. In most cases, project governance follows five steps (outlined in Figure 14). These steps can be completed in a linear process for simple projects, or by a cyclical approach for complex projects. This approach is based on PMBOK’s definition of project governance, which states that project governance is an “oversight function that is aligned with the organisation’s governance model and encompasses the project life cycle.”

These fundamental components fit within the governance life cycle, which requires similar steps to that of the overarching project lifecycle. This is outlined in Figure 14.

Stage 1: Initiate governance process

This outlines the project governance requirements that support and guide the decision-making process, and what will happen at each stage of the project lifecycle. This includes the establishment of project governance requirements, and identifying individuals or groups to fill specific roles within the governance process (e.g., project sponsor, project owner, governance board/committee, project team members). Within this stage, stakeholder engagement should begin, outlining the plan for governance and obtaining feedback, support and consultation. Stage 1 can be defined as the establishment of the governance process.

Stage 2: Plan governance process

This outlines the project governance plan through a process of determining metrics and baseline requirements. Governance plans should include the process for risk and issue management, including mitigation strategies, how and when to update the plan and steps to take when risks occur outside of the plan. Additionally, governance processes should consider quality management, change management, and performance management of the project and development of baselines to support reporting and communication. Stakeholder engagement and communication should be continued throughout this stage, ensuring that updates are made to the process as needed. Stage 2 is the definition of the inclusions, exclusions, assumptions and constraints of the governance process.

Stage 3: Execute governance process

This outlines the execution and application of the governance process, through the implementation of the plan in conjunction with the project management plan. The implementation and execution process requires reporting on the progress of the project in relation to the metrics and baselines outlined in stage 2. Stakeholder engagement and communication must be maintained and managed carefully to ensure reporting occurs as needed. This can include the use of meetings, co-design or communication through digital mechanisms (e.g., emails, report sharing). Stage 3 is the execution of the governance process outlined in the planning and initiation stages.

Stage 4: Monitoring and controlling

This outlines the monitoring and controlling process, which occurs during the execution stage. It is an extension of the execution, by following the baselines and determining where issues are, why they have occurred and the mitigation processes required to get back on track. Stage 4 is the monitoring and controlling of the defined governance processes as outlined within the previous phases.

Stage 5: Closure

This is the closure of the governance process, and is the provision of assurance and validation that the governance process applied was effective and efficient. This requires the project manager, project team and other relevant parties to identify any gaps or improvements that could be made to the process, and in addition provide lessons learned which also outline what worked within the process. Stage 5 is the closure of the governance processes.

Project governance processes have been researched and tested extensively over the last two decades; however, eight fundamental pillars of project governance remain seminal (Alie, 2015; APM 2012). Let’s highlight these.

- Project structure: This includes the organisational structure, the project management structure and the business environment in which the project operates. Organisational structure can be formal, including boards and committees used for oversight, project teams, functional management and experts/contractors brought in as required.

- Roles/people: This pillar is used to ensure that the right people, skills and experience are in the right place at the right time. It is an offset of project structure, where the people leading the boards, committees and governance bodies are critical. Key roles include: project sponsor, project manager, project team members and identification and management of project stakeholders.

- Documentation and communication: Communication and sharing information on the progress and outcomes of the project. This involves working with the stakeholders to provide progress reports, check-ins on work performance and risk discussions.

- Governance frameworks and models: Identification of the appropriate governance model that works with organisational needs. Project managers should consider the appropriate level of governance required for the specific project requirements. This should be based on stakeholder needs and expectations.

- Stakeholder engagement: As part of the governance process and planning, the identification of stakeholders is necessary to ensure the environment is adequately understood. Identification is a complex process, this links to the development of communication and engagement plans to ensure the right information is given to the right people, at the right time.

- Risk and issue management: Risks and issues occur in all projects. Forecasting these risks and issues can support how best to respond. The project team needs to have a consensus on how they will identify, classify and prioritise risks and issues.

- Assurance: Ensures appropriate risk and issue management occurs, based on metrics that show how the project delivery is going. Visibility of project performance is vital. Identified metrics used for assurance, monitoring and reporting should link back to the business case, change management, risk analysis, monitoring deviations in project scope, time, cost and schedule, and quality management.

- Project management control process: A challenging process to execute, as project managers are required to review all tasks and metrics within the project and measurement of performance scope, time, budget and resource baselines. This is an ongoing process, requiring constant performance measurement and responding to issues and making changes as required.

Good project governance will therefore ensure that all of the relationships between stakeholders (both internal and external) are outlined, understood and documented. It will ensure that the engagement and communication plan for stakeholders includes specifics on what information will be provided, when and how. It’s the project manager’s role to ensure that an appropriate review process is documented, to respond to issues or risks as they arise, ensuring that approvals for changes to the project are obtained and recorded as required.

Table 2 below outlines the fundamental requirements of good governance processes.

Table 2. Fundamental requirements of good governance processes

| Documentation | Definition |

| Business case | States objectives of the project, defining in and out of scope elements and assumptions and constraints. |

| Compliance mechanism | Baselines for scope, schedule, budget and quality. |

| Stakeholder engagement | Stakeholder identification, engagement and communication plan and process. |

| Project deliverable specification | Business level requirements list to measure objectives. |

| Roles and responsibilities | Appointment of project management, clear assignment of project team member roles and responsibilities. |

| Project management plan | Current and comprehensive plan of the project, from start to finish. |

| Schedule | Project schedule and work breakdown structure outlining the tasks, activities and deliverables. |

| Document repository | Centralised repository for storing all documentation pertaining to the project. |

| Glossary | Central document outlining the key project terms and definitions. |

| Conflict resolution process | Process for managing any conflicts that arise during the project. |

| Risk management process | A process for identifying, analysing and responding to risks or issues that may arise, including a platform for recording those which have arisen. |

| Quality assurance process | A review of the quality of the deliverables provided. |

Murray (2011) proposed a model for good project governance. According to this model, project governance focuses on five key principles, and an essential component is the alignment to organisational requirements (see Figure 15).

Within this process there are five fundamental components that are required:

- Alignment to organisational governance requirements and overall objectives: Project governance needs to fit within the models and structures of governance that are used for the broader organisation. In addition, the project should contribute in some way to the organisation’s overall objectives. By following organisational objectives, the project governance can be more focused on an outcome, rather than the individual activities or tasks.

- The golden thread of delegated authority: A chain of accountability and oversight. This can include a group or board with specific accountability, or a hierarchical organisational chart, where each person knows their authority level.

- Reporting: Accountable parties report on project progress and performance. This includes periodical reporting, diversion from baselines, or if risks arise.

- Independent assurance: Independent check of the project’s structures, processes and outcomes to ensure objectives have been met. This can also be referred to as quality assurance.

- Decision gates or stage gates: These occur at specific stages within the project life cycle. They are the provision of formal control and decision points in order to obtain approval to continue the project.

Understanding the Project Management Office (PMO)

This module has so far discussed how good governance requires specific and distinct roles and responsibilities, and there are many ways to achieve this. One used commonly in larger organisations is that of a Project Management Office (PMO) or Project Support Office (PSO), which is a permanent structure. It is utilised to support the temporary nature of project teams and the work undertaken in that space. According to the Project Management Institute (PMI) a PMO is a management structure that standardises the project-related governance processes and facilitates the sharing of resources, methodologies, tools, and techniques. The responsibilities of a PMO can range from providing project management support functions to actually being responsible for the direct management of one or more projects (PMI, 2013, p. 10). Let’s discuss this in more detail.

A) Types of PMOs

There are a number of ways to classify PMOs, depending on the level of responsibility the PMO has and its function within the parent organisation. Overall, there are three generic classifications: basic, intermediate and advanced.

(1) Basic PMO (also referred to as PSO). They are used to provide administrative support to a project manager, and hold no responsibility over the development of the project management function and skills growth across the organisation. Fundamentally, they are responsible for supporting rather than managing projects. Basic PMOs are used more commonly in organisations that do not utilise projects consistently and are created for specific projects. They are likely to undertake more administrative duties, including record keeping, change management, communication within the project team and meeting management. Many organisations start with basic (albeit temporary) PMOs, in order to determine their usefulness and viability within the organisation.

(2) Intermediate PMO. These have some responsibility for the growth and development of the function of project management within the parent organisation. Their role is fundamentally focused on maintaining and updating the processes, procedures and mechanisms required to support common operational standards for all projects undertaken within the parent organisation. Intermediate PMOs are responsible for the development and use of standard tools for project management, and the facilitation of monitoring, controlling and project status reporting (e.g., schedules, budgetary, risk, change management and overarching governance).

(3) Advanced PMO. These have a broad range of responsibilities in organisational project management, including setting up and developing the overarching project management function. An advanced PMO leads the design, development, implementation, operation, maintenance and communication processes, procedures and mechanisms enabling the operation of common project management standards. These standards include the definition, selection, introduction, implementation and use of standards, tools, processes, procedures, and facilitate the monitoring, controlling, management and status reporting of the projects (e.g., scheduling, budgetary, risk, integration, status reporting, change management and governance). In order to establish an advanced PMO, the employees need to be specialists in project management (having relevant skills, experience and knowledge). This is especially important as they are required to make decisions on the selection of projects, the creation and distribution of standardised documentation and the continuous development of the project teams to ensure they are following the same processes.

B) Level of PMO control

Another way organisations determine the type of PMO that they require or hold is by understanding the level of interest, influence and control that it should have over their projects. According to PMI, there are three levels of control that PMOs commonly hold: supportive, controlling and directive.

(1) Supportive: Supportive PMOs (or PSOs) are consultative in nature, supplying templates, best practices, training, information access and lessons learned from previous projects. Supportive PMOs serve as a project repository. The degree of control provided by the PMO is low.

(2) Controlling: Controlling PMOs are supportive while also setting compliance requirements for each project. Compliance commonly involves the use of project management frameworks and methods provided by the PMO, which include templates, forms, tools and governance procedures. Within these PMOs the level of control is moderate.

(3) Directive: Directive PMOs control projects through direct management of projects. The degree of control of these PMOs is high (PMI, 2013, p. 11).

C) Services

Services provided by PMOs are dependent on the parent organisation and are largely influenced by organisational size, maturity and project management capabilities, skills and experience. Within smaller organisations (which are often less mature), that undertake fewer projects, their PMO may provide a smaller range of services. Whereas larger organisations that undertake more projects and have a greater need for ongoing project support may have a larger service offerings, in turn providing better support (APM, 2012; PMI, 2013). Some of the primary services provided by PMOs include:

- Plan and schedule: Every PMO, regardless of size, type or level of control, will support planning and scheduling. For a basic PMO this can include inputting and updating information provided by the project manager. For an advanced PMO this can mean leading this process, obtaining relevant information, liaising with stakeholders and the project team, drafting schedules and developing the resource requirements. To achieve this, the PMO will draw from their skills and the experiences obtained from working on previous projects.

- Administration: As for planning and scheduling, every PMO supports administration to some degree. Basic PMOs provide the project manager with administrative support; however, the project manager is accountable for completing the work. Advanced PMOs have more influence and accountability for the administrative components of the project and supporting the project manager. This includes collation of information, document preparation, business case and financial viability reports, and stage reviews of project process.

- Reporting: A primary service of all PMOs, types and levels of reporting are dependent on the PMO type. Basic PMOs report to the project manager, who is responsible for reporting to project sponsors and organisational management, whereas intermediate or advanced PMOs interact directly with the project manager and corresponding team members to create reports. The role of the PMO in the creation of reports will depend on the roles and responsibilities of the project manager and the PMO team members, governance structure and the capabilities within each space.

- Professional development: PMOs are commonly responsible for the development of organisational skills, capabilities and knowledge of project management. This can include training sessions, development of a network of project management support or bringing in externals. Within organisations with a basic PMO, they may be supported by the learning and development or human resource departments.

- Financial control: PMOs may play a role in the financial management and control of a project. This can include budget creation, monitoring and controlling, and closure, which may be done with the support of the project team or the accounting department.

D) PMO relationships

Due to the varying nature of the types of PMOs, their roles, responsibilities and capabilities, the relationships they develop and maintain within an organisation and across projects will differ depending on many factors. Fundamentally, PMOs either support or control a project and the project manager. All roles and responsibilities need to be documented, defined and clearly communicated.

The roles need to clearly outline the differences between the PMO’s and project manager’s responsibilities, especially when it comes to stakeholder management. For example:

- The project manager’s role should be focused on specific project objectives and outcomes, whereas the PMO manages the administrative components of a project (e.g., the creation and ongoing development of templates, tasks and documentation).

- The project manager controls project resources in order to meet project objectives, while the PMO manages the use of shared resources more broadly.

- The project manager manages constraints (scope, schedule, cost, quality, etc.) of their project, whereas the PMO manages methods, standards, risks/opportunities, metrics, and interdependencies among projects at the organisational level (PMI 2013, p. 12).

PMOs and project managers may not always have a smooth relationship, especially with the decision to progress specific projects being outside of the role of the project manager. However, communication between the PMO and the project manager needs to be enduring to ensure all governance requirements are completed and up-to-date, and differences are resolved.

Test your Knowledge

Project governance and the role of stakeholders

Stakeholders play a significant role in all aspects of projects, from start to finish (Muller, 2009). The role of internal and external stakeholders within project governance emphasises the need for establishing clear and structured relationships across the different stakeholder groups (as per their needs, expectations and preferences) (Freeman, 2001). Therefore, within project governance, a framework is recommended that outlines the roles and relationships of stakeholders. This includes the roles, relationships and positions of the stakeholders, inside and outside of the organisation. Unfortunately, stakeholder management is not always an easy process. Derakhshan et al.’s (2019) research shows that a number of common mistakes in managing stakeholders and their role within project governance can be avoided by:

- understanding both internal and external stakeholders, being aware that external stakeholders can play a significant and fundamental role in project outcomes

- clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders

- ensuring that governance draws attention to the context of stakeholders, including their required engagement needs and communication requirements

- establishing direct contact with external stakeholders to obtain project support.

In sum, if both the project manager and the PMO exist within the structure of the project host organisation, both should be involved in designing, implementing and managing the governance aspects of the project. Project governance needs to be functional to a project in the same way corporate governance is to an organisation. Consequently, both the project manager and the PMO should be directly involved with the project governance procedures of the organisation to be able to effectively integrate these to the project environment and efficiently manage internal and external stakeholders.

Key Takeaways

- The governance style of the organisation that owns and leads the project is a crucial element determining project governance and what is regarded important in the project.

- PMOs, according to the PMI, are management structures that standardise project-related governance procedures and promote the sharing of resources, methods, tools, and techniques across project teams and stakeholders.

- It is advised that a framework be used to explain the responsibilities and relationships of project stakeholders as part of the project governance process. Inside and outside the organisation, stakeholders’ responsibilities, connections, and positions are all considered in this context as well. The unfortunate reality is that stakeholder management is not always a straightforward procedure.

References

Abu Hassim, A., Kajewski, S., & Trigunarsyah, B. (2011). The importance of project governance framework in project procurement planning. Procedia Engineering, 14, 1929-1937.

Alie, S. S. (2015). Project governance: #1 critical success factor. Project Management Institute.

Association for Project Management (APM). (2009). A guide to the governance aspects of project sponsorship. APM Publishing.

APM. (2012). APM Body of Knowledge (6th ed.). APM Publishing.

Bekker, M. C. (2015). Project governance: The definition and leadership dilemma. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 194, 33-43.

Bekker. M. C. (2014). Project governance “Schools of Thought”. South African Journal of Economic and Management Science, 17, 22-32.

Bekker, M. C., & Steyn, H. (2009). Defining project governance for large capital projects. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 20(2), 81-92.

Crawford, L. H., & Helm, J. (2009). Government and governance: The value of project management in the public sector. Project Management Journal, 40(1), 73-87.

Crawford, L., Cooke-Davies, T., Hobbs, B., Labuschagne, L., Remington, K., &Chen, P. (2008). Governance and support in the sponsoring of projects and programs. Project Management Journal, 39, S43–S55.

Derakhshan, R., Turner, R., & Mancini, M. (2019). Project governance and stakeholders: A literature review. International Journal of Project Management, 37(1), 98-116.

Freeman, R. E. (2001). A stakeholder theory of the modern corporation. Perspective Business Ethics, 3.

Garland, R. (2009). Project governance: A practical guide to effective project decision making. Kogan Page.

ISO. (2012). ISO 21500 Guidance on project management. International Organization for Standardization [Online]. Available at http://www.iso.org/ iso/ home/ standards.htm (Accessed 28 March 2022).

Joslin, R., & Muller, R. (2016). The relationship between project governance and project success. International Journal of Project Management, 34(3), 613-626.

Morris, P. W. G., & Geraldi, J. (2011). Managing the institutional context for projects. Project Management Journal, 42(6), 20-32.

Muller, R. (2009). Project governance. Gower Publishing Limited.

Muller, R., Andersen, E. S., Kvalnes, O., Shao, J., Sankaran, S., Turner, J. R., Biesenthal, C., Walker, D. W. T., & Gudergan, S. (2013). The interrelationship of governance, trust and ethics in temporary organisations. Project Management Journal, 44(4), 26-34.

Murray, A. (2011). White Paper: PRINCE2 and Governance. The Stationary Office.

Osei-Tutu, E., Badu, E., & Owusu-Manu, D. (2010). Exploring corruption practices in public procurement of infrastructural projects in Ghana. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 3(2), 236-256.

Project Management Institute. (2013). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK Guide). Project Management Institute Inc.

Townsend, C. (2014). Project governance. 17 Success Secrets—17 most asked questions on project governance: What you need to know. Emereo Publishing.

Turner. J. R. (2006). Towards a theory of project management: The nature of the project governance and project management. International Journal of Project Management, 24(2), 93-95.

Walker, D., & Rowlinson, S. (2008). Procurement systems: A cross-industry project management perspective. Taylor & Francis Group.