Module 3. Asset management standards and models

Overview

The objective of this module is to provide a critical review of the existent asset management (AM) frameworks by presenting a current overview of AM standards. For instance, Australia and New Zealand, have formalised the International Infrastructure Management Manual (IIMM) AM standard. Other countries like the United Kingdom have used the PAS 55 AS standard. Taking into consideration that there has been a variety of standards frameworks implemented, the introduction of an international standard for asset management in 2014 (i.e., the ISO 55000 suite) was much needed. The ISO 55000 suite is the first set of global standards representing a consensus for the asset management community.

A brief overview of the Australia and New Zealand standard as well as the ISO 55000 described above is presented in the following section.

The International Infrastructure Management Manual (IIMM)

As a result of the increase in energy prices and interest rates after the global economic crisis, the Australian government implemented a number of broad-based economic reforms in 1986. These reforms triggered the AM concept for the maintenance of public facilities, which since then, has become internationally recognised. The majority of our infrastructure has been developed in accordance with this philosophy. Initially focusing on highways, the national asset management councils were established, and the Asset Management Manual was released in its first version in 1996. The International Infrastructure Management Manual (IIMM) was first published in 2000 solely by Australia, with further updates appearing in 2002, 2006, and 2011, which integrated New Zealand regulations.

The IIMM is a collection of guidelines that explain how to implement the standards for infrastructure asset management. The guidebook was prepared with input from several nations, and from both public and commercial organisations. Asset managers, asset planners, operators, maintainers, and developers have since been able to use this manual, as the IIMM emphasises universal application to ensure that it may be used by everyone involved in AM and across cultural locations. In the IIMM design, the decision to use a Maturity Index was strategically aimed to assign different levels of difficulty to evaluate and quantify different AM activities. The activities ranged from the most basic to the most advanced, and were assigned to organisations that were just getting started with asset management to organisations that had a lot of experience in this field.

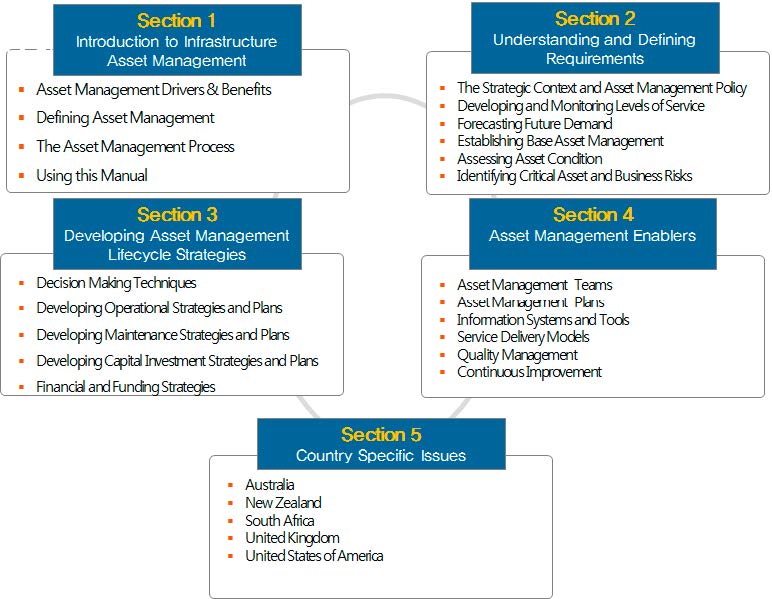

The IIMM is divided into five sections, as seen in Figure 8 below. Section 1 provides an overview of the AM infrastructure. It describes the advantages of AM, the definition of AM, the AM process, and the value of using the manual. Section 2 discusses recognising and defining clear asset requirements, and describes AM policy/strategy, service levels, anticipating future demand, asset condition evaluation, and risk management. Section 3 discusses establishing AM life cycle tactics, expands on decision-making procedures, operational and maintenance as well as capital investment strategies and plans. Section 4 discusses AM facilitators: asset management teams, delivery methodologies, quality management, and continuous improvement. Lastly, Section 5 discusses issues that are peculiar to each country (i.e., Australia and New Zealand, with recent working groups from the United States, South Africa and the UK expanding its adoption) and it provides a summary of the infrastructure and financial regulations in these countries.

Australia and New Zealand have fully adopted the IIMM. However, as infrastructure has been recognised as the foundation of a country’s economy, then it must also fulfil the ISO standards for the country to be globally competitive. Therefore the Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia (IPWEA) updated the IIMM edition to introduce the latest ISO 55000 Asset Management Standards. This can be found in the 5th IIMM edition. It appears that this edition of the IIMM represents a substantial advancement in the following critical areas, as indicated by IPWEA: Making a business case for AM and identifying critical success elements, directly guiding strategic asset management plans (SAMP) and policies. In this assessment plan, IIMM addresses AM objectives, risk management, leadership and communication, operational strategies and planning, asset management systems, information management, asset management maturity, asset management performance measurement and auditing, infrastructure resilience assessment and management, as well as asset management maturity. Today, IIMM still holds a critical role in achieving best practices in the AM industry.

But what are the ISO 55000 Standards? And what is its role in AM?

The ISO 55000 family of standards

All international management systems, including ISO 55000 asset management systems, are recognised as a framework of essential drivers and procedures in the industry, and as such, they are included in the ISO 55000 portfolio of standards. In addition to being based on real-world AM skills and practices from across the world that have been recognised and endorsed by an expanded panel of international experts, these standards have several other significant advantages. It is worth noting that the ISO 55000 suite of standards was developed by the ISO Committee PC251 with the participation of 31 countries, making it the most broadly approved global asset management system available today. According to the standard, the purpose is:

Throughout the process of developing ISO 55000, a common and successful method has been built, and this methodology can be applied to a variety of assets and organisational structures across the world.

Currently, the ISO 5500x standard is in use globally, and it encompasses three fundamental specifications: a) ISO 55000 Asset management: Overview, concepts, and terminology, b) ISO 55001 Asset management: Control systems – Specifications, and c) ISO 55002 Asset management: Management systems – Recommendations for ISO 55001 implementation.

The ISO 55000 package of standards is built on a strong foundation. ISO 55000 is relevant to any firm or type of asset – tangible or intangible – as long as the assets are a crucial component in the achievement of the business objectives. Yet, ISO 55001 in particular, is the most essential standard in the ISO group since it specifies the standards that must be met in order to implement an effective AM system. It describes “what” should be included in the asset management system as well as “how” to obtain this information. QUALITY has also been established as a criterion for AM by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 55001).

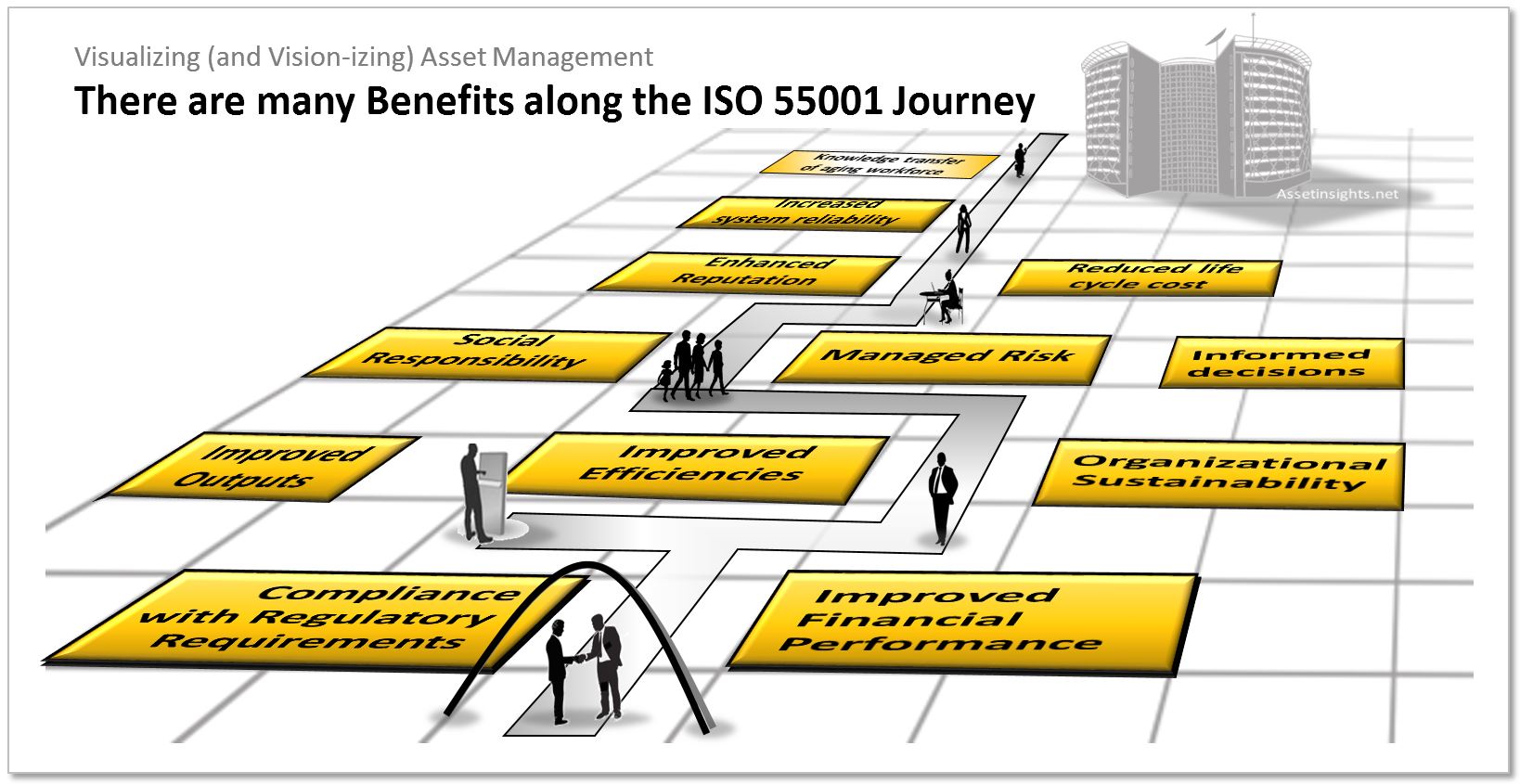

In sum, the ISO 55001 standards focus on the benefits of AM integration for an enterprise, while emphasising the four pillars upon which such integration should be built: generating value for the organisation and its beneficiaries through resource utilisation, promoting the overall sustainability of the organisation in order to achieve organisational goals, and managerial leadership based on employee commitment and political involvement in the organisation. At the same time, it is necessary to emphasise that these foundations cannot be seen as the underlying principles of good resource management, but rather as the outcome of continuous resource management activities and facilitation. These benefits are reflected in Figure 9 below.

Reading: The contemporary landscape of asset management systems

The article titled “The contemporary landscape of asset management systems” by Konstantakos et al. (2019) presents an excellent overview of the AM standards discussed above. Please click the link below.

Asset management components

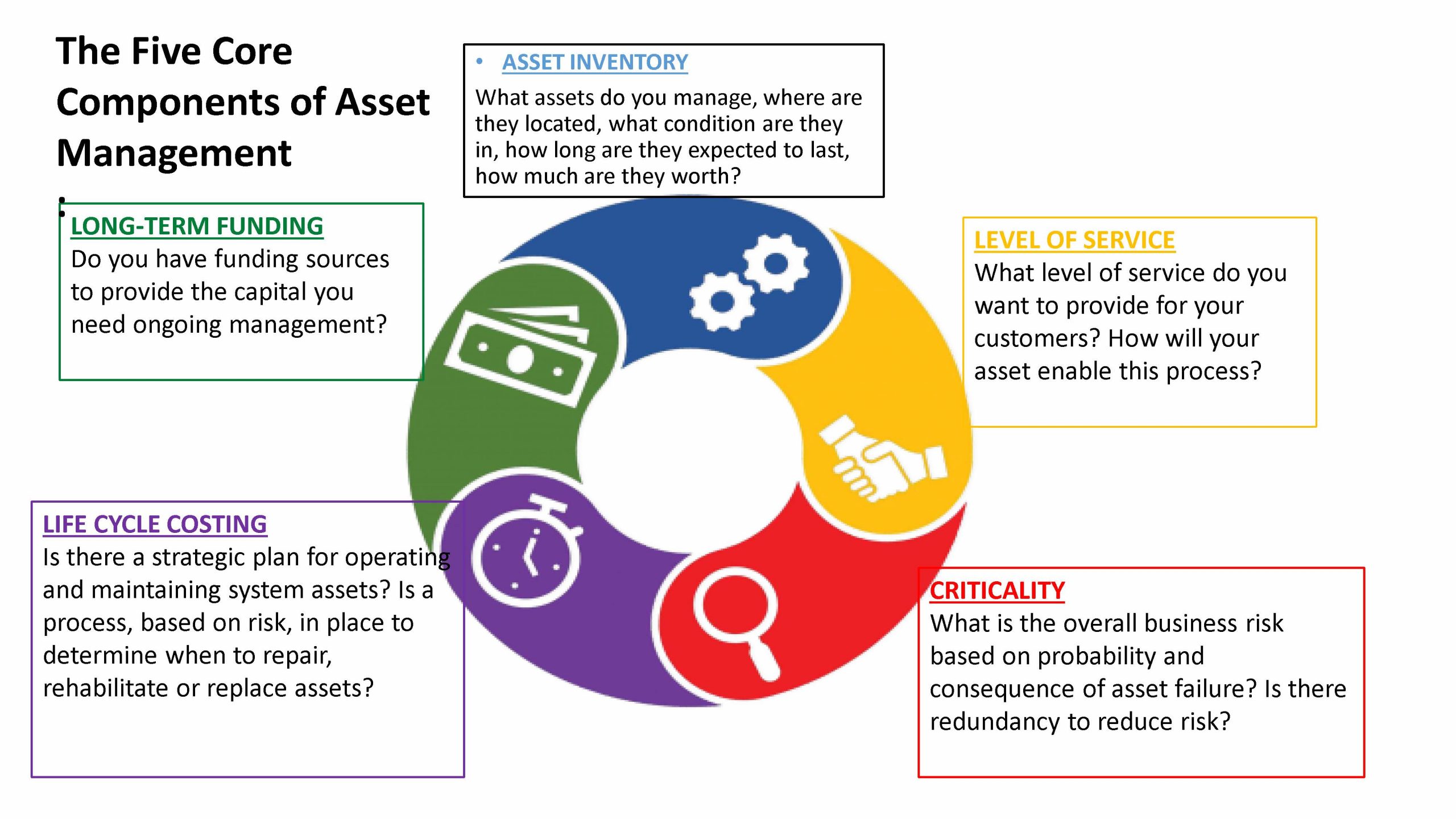

There are multiple variations of asset models and frameworks as well as AM software in the market. In fact, as mentioned earlier, almost every organisation has developed an AM system in-house or adopted automated AM systems packages to align with their strategies and business mission(s). Consequently, we are unable to provide you with a unique model as a benchmark to adopt. However, let’s discuss the five critical components which are common for AM. The Asset Management Center for Water and the Environment of the Georgia Association of Asset Water Professionals in the United States has created a simplified version of these components. Figure 10 highlights these five components, including: asset inventory, level of service, criticality, life cycle costing and long-term funding.

Inventory of assets

Asset inventories should be a clear reflection of what the organisation own as well as the condition of its assets. To begin compiling the inventory, the role of the project manager is to gather as much information as possible about each unique asset. The type of information that is recorded by the organisation about the assets should include the kind, size, location, condition, remaining useful life, and replacement costs. These resources will aid the project manager in selecting the most pertinent data gathering methods, and the most pertinent data utilisation strategies, allowing project managers to have complete control over the organisation’s assets.

The initial inventory cannot be created using a one-size-fits-all method since each organisation’s situation and assets are unique. However, project managers are advised to collect the following information as quickly as possible:

- Collect as much intangible knowledge and information about where assets have been placed and the specific location of those items. If tangible information, such as a system map, is available, they can be referenced to at various points throughout data collation.

- Refer to the system’s as-built record drawings, as well as to additional engineering drawings, if needed. Interview potential people who are knowledgeable about the AM process to get specific information.

Following the creation of a master inventory database of assets, it is important to determine the location of such assets. A visual representation of asset locations is a critical component of AM. The map might be simple (hand drawn) or as complicated as technological capabilities allow it to be (Geographic Information System). In terms of benefits, the most significant is that it may be used to track changes in the asset inventory as well as failures of assets in maintenance records.

After the map has been created, the location of the object should be documented in the asset inventory database and linked to the mapping system. Furthermore, location information allows for the establishment of asset groups, and when a single asset in a given location and or department is replaced, the issue of whether or not additional assets in the same location should be replaced at the same time may be answered.

When assets are recorded, it is also critical to determine their current condition. A preliminary condition assessment can be carried out by assembling individuals who have current or historical knowledge of the system and asking them to score the asset’s condition on a productivity-operational scale.

Level of service

Service organisations, in particular, often have competing priorities and limited funds. Therefore, the project manager must determine what the organisation’s customer needs are and if the organisation is capable of providing and/or matching their asset with the customer service specifications. In project management terms, the scope of the AM is required to align with the stakeholder’s specifications to maximise the service level. When customers have a say in what they wish to obtain, they are more willing to pay for it. Defining the right level of service will allow project managers to clearly communicate what it is that the organisation service or products will do for the customer, which is the value of the project and the benefits of investing in the right assets. AM can help project managers define the level of service of the project deliverables.

Critically evaluating risks

It is important to identify key assets allocated to the project and inside the organisation. Another key component is being able to critically recognise which assets are essential for risk management and develop a plan for how to protect them. Think about this:

Assets are defined as critical, based on their relevance to the proper productivity and functioning of an organisation. Having knowledge of the potential and ramification of risks helps to develop criticality in a given situation. A project manager must first determine what information it has about the possibility of a certain asset failing before proceeding with the project. To aid in this examination, a project manager should consider the following factors: the asset’s age, condition assessment, failure history, designed life expectation, current maintenance practices and methods and knowledge regarding the likelihood of that type of asset failing (if applicable). The likelihood of an asset failing increases when the asset is old, has a lengthy history of failure, or has a bad condition rating. The likelihood of a failure may be reduced significantly if an asset is newer, has a limited or no failure history, and is rated in good to exceptional condition. Therefore, the criticality factor associated with an asset can be assigned in a manner aligned with how the condition rating is allocated.

When analysing the consequences of a failure, a project manager should consider all of the conceivable outcomes as well as the related costs. In addition to the cost of repair, the costs of asset loss may include the social cost of asset loss (e.g., a reduction in customer service level, if applicable), and any other associated costs or asset losses. In the event that any of these expenses is severe or if a large number of changes develop as a result of the failure, it can be extremely expensive. The asset’s consequence factor can be, therefore, allocated and managed in the life cycle costing.

Life cycle costing

Understanding the life cycle costs of an asset gives the organisation the ability to optimise their investment in the asset. In order to understand the life cycle costing, project managers need to understand purchase costs, maintenance history and repair history. With this information project managers are in a better position to begin to look at how much maintenance an asset should receive to extend its life and when an asset should ideally be replaced. These resources will help inform cost benefit analyses and possible asset maintenance regimes among other things.

The total useful life of an asset is the time from when the asset is fully operating until the asset is no longer able to perform its required function for the project and/or organisation. The useful life remaining for the asset is the time from today’s date until the asset is no longer expected to meet its desired purpose. It is also required that project managers learn to establish the replacement cost of an asset as well as the asset’s useful life in order to plan for its replacement when needed. When calculating the replacement cost, it is necessary to take into consideration both the expenses of replacing an existing asset with a new one and the costs connected with disposing of the prior asset. When calculating the replacement cost, it is important to include the estimated cost of replacing it in today’s currency.

Long-term funding

Identifying the financial requirements for managing the organisation’s assets in line with stakeholder service level expectations is critical to achieving success (note that the stakeholder group may include regulators, customers, project team, sponsors, legislative groups, etc.). Also important is the understanding of existing and future costs associated with asset renewal, maintenance, and replacement, both current and predicted. These expenses serve as the foundation for developing budgets for operations, maintenance, and capital projects, which are then evaluated by decision-makers. In order to satisfy long-term financial responsibilities, it is necessary that the project manager starts financial planning as early as possible.

Overall, we also recommend that the project manager keep some key performance indicators (KPIs). These metrics are agreed with senior management and the project team executing the project. This is important as these measures may be used to track an organisation’s progress towards its AM objectives over time. KPIs should thus be aligned with strategic objectives to track and report progress towards those objectives. Data from supporting data management systems may be gathered and used to produce metrics, also known as key performance indicators, that give insight into the success of AM projects, among other things (IAM, 2015).

By now, you must agree that having a well-managed AM framework has several important advantages, one of which is that it results in long-term cost savings but also, in the short term it promotes the organisation’s competitive advantage by addressing the service needs and expectations of their customers.

Test your knowledge

Blueprint steps for AM strategic framework plan

Please note that this is only a guide. Various versions/approaches exist in the field of AM. We encourage you to conduct some research and design or adopt an appropriate plan in accordance with your organisation’s structure, strategy and objectives. However, the following steps will provide you with a solid foundation. Please note that each activity listed under these steps requires assignment of a key milestone. Project managers are the most qualified to identify adequate milestones.

Step 1. An authorisation/approval activity is required prior to commencement. Dates and responsible position: line of approval needs to be documented.

| Name– Position – Responsibility | Signature | Date |

Step 2. Communication: Control Officer – A plan for internal and external communication is required during the AM life cycle.

| Name– Position – Responsibility | Communication Strategy | Status- Action – Change | Date |

Step 3. AM scope and Statement of Work

| Activities | Tasks |

| Organisation Objectives | Summarise the organisation’s core mission and core objectives. |

| Strategic Direction | Statement of the organisation’s objectives and how these are aligned with the overall strategy, operation plans, and KPIs. |

| Forecasting | Requires a clear identification of both internal and external assets, as well as the presentation of a quick assets inventory aligned with the organisation’s objectives and service/product deliverables. Think how these assets are impacting the project deliverables. |

| Scope Planning | Plan and rank the degree of impacts that the external environment and stakeholders may have on the organisation’s assets and outcomes (i.e., services and products). |

| AM Objectives | Cluster/classify the asset requirement for the organisation, and prioritise these in accordance to the organisation’s objectives. |

Step 4. In line with the five AM components, an asset portfolio needs to be established.

| Activities | Tasks |

| Asset Inventory | A summary of the organisation’s existing assets and evaluation and/or status of their life cycle. |

| Asset Life Cycle Cost Evaluation | An assessment of how well the assets are performing in supporting the organisation’s strategy. Once the life cycle of the asset is clearly evaluated, an indicative picture of their stage, performance and cost value is required |

| Risk Evaluation | Identify potential risks for each asset and assign a scale to their degree of impact these may have in the organisation’s overall objective. |

Step 5. A formal and evidence-based asset portfolio plan is design. This is underlined by all the data and information collected in set 1, 2, 3 and 4.

| Activities | Tasks |

| Maintenance | Operational activities as well as maintenance management plans need to be listed in order to manage any previous risks identified. |

| Buy or Fix? | Established KPIs for asset renewals and acquisitions of new assets in the short, medium and long term.

|

| Financial Plan | Provide summary of financial approvals, variations and/or control methods reacting to risks. |

| Disposal | Identify key assets that are no longer cost effective to maintain and operate, or do not show a long life cycle, and therefore are considered to be underperforming or unproductive.

|

Step 6. Continuous improvement. Project managers are required to provide an ongoing evaluation plan to improve the organisation’s asset management frameworks and practices. More important is the project manager’s responsibility to make sure that the project host organisation has a current AM strategy in place. As we know, AM is dynamic and evolves in line with technological changes, global economic changes, monetary inflation, logistics disruptions, and other factors imposing changes on the organisation’s operational environment. Continuous reviews, evaluations and opportunity assessments are a must.

Test your knowledge

Key Takeaways

- The (IIMM was first published in 2000 solely by Australia. It is still current today, but jointly with New Zealand, South Africa, UK and the United States.

- ISO 55000 is now considered a required standard for AM.

- IPWEA’s five components, including asset inventory, level of service, criticality, life cycle costing and long-term funding, are a current foundation for designing strategic AM models and/or frameworks.

- The role of project managers continues to be expanded in the design of strategic AM frameworks. A key role they play is in the data and information collection to start the design and plan of the asset inventory.

- Key milestones are needed as a review process under each of the seven steps suggested for the design of AM systems and processes.

References

International Organization for Standardization. (2014). Asset management — management systems, Guidelines for the application of ISO 55001, ISO 55002:2014(E), 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2724-3

IAM. (2015). Asset management: An anatomy. Version 3, Tech. Rep., The Institute of Asset Management.

IPWEA (2015). IIMM Supplement 2015: Meeting ISO 55001 Requirements for Asset Management. The Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia.

Lee, S., Park, S., & Kim, J. (2015). Suggestion for a framework for a sustainable infrastructure asset management manual in Korea. Sustainability, 7, 15003-15028. doi:10.3390/su71115003. Open access.

Transportation Asset Management in Australia, Canada, England, and New Zealand. (2005). Federal Highway Administration.

Whyte, J., Stasis, A., & Lindkvist, C. (2016). Managing change in the delivery of complex projects: Configuration management, asset information and “big data.” International Journal of Project Management, 34(2), 339–351.