Module 1. Definitions and importance of asset management and project governance

Overview: What is asset management?

Asset management (AM), as practised today, is a fundamentally new way of thinking about physical assets and how to use them to create value for the organisation. Because AM is such a vast topic, it should come as no surprise that a number of AM strategies have been formed on the basis of unique organisational practices or distinct personal understanding of individual specialists. However, we can say that AM is a strategic approach to maximising the value of an organisation’s assets. Therefore, it represents one of the organisation’s critical comprehensive and proactive competitive advantage philosophies.

AM is a set of ideas that can help a company improve how it does business, makes decisions, and processes, uses, and communicates data related to its infrastructure management. AM is largely concerned with how an organisation allocates and uses resources, including money, people, skills, and information. It offers a consistent, integrated framework for planning, programme formulation, and programme delivery across the organisation’s various assets. Therefore, it is becoming a critical component of project management.

AM encourages several quality standards within the organisation’s processes, such as evaluating all options at each stage of their decision-making process, conducting project economic analysis from a long-term perspective, assessing trade-offs across initiatives, monitoring program effectiveness and system performance, and leveraging management and information systems throughout the AM cycle. All of these are critical aspects within the project management life cycle. AM is also goal-oriented, with explicit performance and accountability metrics. It is steered by policy objectives and goals and therefore we suggest this be considered, particularly in phase one and two of the project management life cycle (i.e., the design and planning phases).

It can also be stated that AM refers to the management of tangible and intangible project properties, which are typically the processes of managing and rearranging the project deliverables (i.e., outcomes). AM encompasses the classic project management area of version control but in more recent times it has also begun to cover new areas of project property control. Furthermore, with times of disruption and ongoing digital transformation, we would say that the AM process should encompass the whole project life cycle, beginning with design and procurement and continuing through operation and maintenance before finally being retired, resulting in even more project value.

Asset management strategy

Organisational strategy creation and implementation are influenced by actions within the AM system, just as they are by other activities within the organisation. Developing strategy is an ongoing activity that is dependent on the interplay between corporate or company plans and the actions of the organisation in which they are implemented. To achieve sustained competitive advantage, strategy formulation should be viewed as an organisational capacity that can be cultivated at many levels within the organisational structure (Gordon, 1998). AM is thought to be a component of the organisational strategic management system, and to play a role in the creation and execution of organisational strategies. As a result, any architecture for the asset management system should identify the system’s role in the creation and implementation of a strategy.

It is believed that the process of value creation may be discovered by the performance of the asset under consideration. Performance of the output is a function of the production or operation process, and it is dependent on the capability and performance of assets throughout the project utilisation phase. When it comes to the capability and performance of assets during this phase, the capability and performance of the design procedures throughout the design phase are critical factors to consider if we aim to reach a strategic framework. So, the execution of asset-related activities throughout their life cycle stages is critical to the value generating the project’s success.

Applied to any organisation, AM is also a strategic business model that provides real ways to demonstrate the following characteristics: good asset ownership, effective asset management and service management, responsible stewardship, and long-term sustainability progress. But there is a misconception that AM is a strategic approach which aims only to collect and integrate current management systems and data and, therefore, is perceived to be a continuous process. However, it goes far further than that. The strategic value is in its ability to build on existing procedures and tools, as well as complement and expand current practice, all via a process of continual evaluation and development. This is a process that results in the creation of an AM blueprint, which acts as a roadmap for improving business and service delivery, and one that you are in charge of as a project manager.

Organisations employ specialised frameworks and guidelines for their individual assets, which are typically taken from the asset manufacturers, but their overall system management is typically established experimentally via their own practice and emphasis. As a result, there are many various viewpoints on what “Total Asset Management Strategy” implies to each distinct organisation’s structure. Therefore, we can state that the strategy is shaped around the amount of complexity, design, and specific assets engaged in the organisation.

As mentioned earlier, for AM to make a significant contribution to an organisation’s success, important activities, connections, and procedures must be identified, formed, and managed inside the business. In other words, an AM strategy must be investigated, with fundamental AM procedures and enablers established as part of a comprehensive approach to achieving the organisation’s strategic goals (Clash and Delaney, 2000).

Projects are responsible for the creation of the assets that will be managed, as well as for the enhancement and some upkeep of such assets. The management of assets and the management of projects are therefore intertwined in many ways. It is therefore important that you, as the project manager, partake in AM frameworks as early as possible and get familiar with all the required actions within AM.

Organisational departments have traditionally been responsible for actions that are connected to assets or life cycle processes, such as asset design, asset operation, and asset maintenance, among other things. In addition to the above, other asset management activities, such as measurement and analysis, planning, development, modification, and any investment work are always carried out by relevant departments for the unique purposes of each department. Yet, the project manager should be a key stakeholder in these actions. Budgets are always stated, resources are always allocated, and information regarding the health and performance of assets is always collected in some form or another. These operations are carried out by numerous departments within the business; however, they may not be integrated and maximised for the achievement of the firm’s strategic objectives. It is here that project managers undertake an important task: integration.

To achieve the organisational strategy, the objective of this new discipline known as AM is to generate collaborative activities inside the organisation’s system, which are then carried out by the organisation’s employees and subsequently support the organisation’s strategy. However, if this is misguided, the strategic support to the organisation can be jeopardised. Can the project manager also take a leadership role in this case? There is no simple answer to this question. AM is such a emergent discipline and concept that there is still lots of research to be conducted for us to learn more. But what is clear is that it is a critical component for us, as project managers, to manage.

Researchers have produced a bewildering array of management system types relating to physical assets over the course of history. Maintenance management, strategic AM, engineering AM, property AM, infrastructure AM, enterprise AM, and other commonly used words are examples of this diversity. As a result, it is clear that AM is important to all sorts of industries and all of the assets that are engaged in those industries. Accordingly, AM systems should be tailored to the alignment, culture and commercial objectives of the individual company or sector in which they are used.

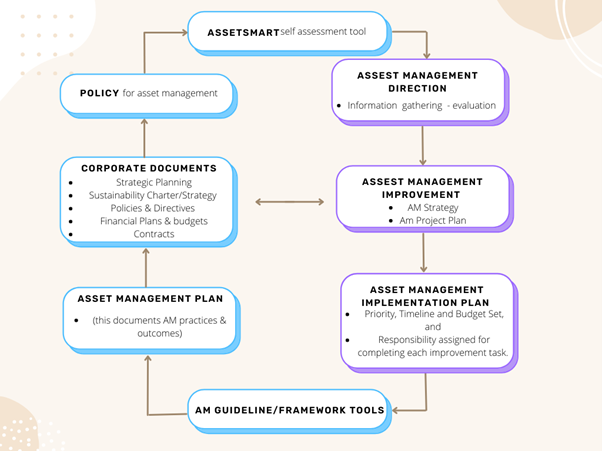

In the early phases of establishing an AM approach, there are typically a great number of unknowns and assumptions that must be made in order to proceed. As a result, it is necessary to begin with a straightforward holistic (i.e., broad) strategy to generate early momentum and establish the foundations of understanding, information, and procedures in the organisation. This initial effort may then be modified by the project manager and the project management team, adapted, and expanded in terms of depth of information and complexity with the use of reference texts, as well as other sources. Figure 1 shows a holistic approach to AM strategy. Each of the processes highlighted in Figure 1 identifies an asset management practice to be implemented. Some of these practices will be discussed in a later module.

Let’s pause and test our knowledge:

An overview of the process of asset management

Taking a third priority within the holistic AM strategy, it is worth noting that an AM plan can be actioned quickly as it is a simple and straightforward process. There are some stages in an asset life cycle that are more prevalent than others, even though the organisation and structure of an asset life cycle may fluctuate amongst various enterprises. It is possible to divide an asset life cycle into four distinct stages. Let’s look at these four stages.

-

Make a plan

On the basis of an examination of current assets, planning can assist in determining the need for a particular item, as well as the critical skill needed for the project. This is accomplished by the implementation of a management system that can analyse trends and data, providing the decision-makers with the ability to determine the necessity for the asset and the value it may offer to the organisation’s operations. For all stakeholders, from finance teams to operators, the early stage of an asset’s life cycle is critical. The choice to acquire an asset is based on the asset’s ability to meet the demands of the organisation and the needs for its projects, in addition, of course, to contributing to the company’s operations and creating income.

-

Obtaining the project property: An organisation’s asset

Identifying, evaluating and purchasing an asset is the next step. In this process, the project manager makes sure that enough research has been conducted to confirm that the asset is a critical resource required to improve operations and support the successful deliverables of the project. This step will also include consideration of the financial aspects of acquiring an item that is within the parameters of a budget that was established during the planning stage. Using an AM system, after the asset has been procured and deployed, it can then be tracked throughout its full life cycle, allowing for greater efficiency and accountability.

-

Operations and maintenance

Following the installation of the asset, the following stage is operation and maintenance, which is the most time-consuming part of an asset’s life cycle. This stage describes how the asset will be used and managed, as well as any maintenance and repairs that may be required in the future. After being placed for its intended use inside the organisation, the asset has begun to improve operations while also contributing to the generation of income. In addition, updates, patch fixes, licences, and audits must be addressed immediately. During operation, an asset will be monitored and examined on a regular basis for any performance concerns that may arise unexpectedly. This is the point at which maintenance and repairs begin to become more frequent occurrences and project managers are required.

As we know, in order to extend the asset’s life and worth as much as possible, regular maintenance is required as an asset ages and wear and tear grows. Additionally, alterations and improvements are necessary in order to maintain assets to be up to date with the constant technology changes and ongoing disruptive environment. Maintenance strategies are unique to each organisation. There are many who favour a reactive maintenance method, while others prefer a predictive or preventive maintenance plan. Even so, each maintenance approach strives to achieve certain goals, such as:

- keeping downtime to a minimum

- keeping emergency repair expenditures to a minimum

- increasing the uptime of equipment

- extending the useful life of an asset to perform better than it did originally by always identifying and addressing possible improvement areas.

-

Disposal of waste

Finally, at the end of an asset’s useful life, it is removed from service and either sold, repurposed, thrown away, or recycled, depending on the circumstances. Even though an asset has no commercial value at this point, it may nevertheless need to be disposed of in an environmentally friendly manner. Depending on the circumstances, this procedure might potentially include disassembling the item piece by piece or wiping it clean of all data. If, on the other hand, this sort of asset is still required for operating purposes, a replacement is planned, and the asset life cycle can be restarted from the beginning.

Some of the AM values

There is no doubt that organisations that make an investment in AM receive a variety of rewards. However, not all these advantages are associated with financial rewards. Asset monitoring in real time provides an ongoing stream of data, encourages accountability and, with the support of an appropriate AM system, helps maintain planning and equipment maintenance on schedule and on budget.

There are other various possible values.

Recognition of business requirements: All AM techniques recognise the variability in “optimal” conditions connected with the business environment and support logical decisions made on the basis of such aspects, whether or not they are explicitly stated.

Promote best practices: The adoption of techniques such as systems engineering is implicit in standards such as ISO 55000, as well as explicitly stated in more general AM literature, for example, the Asset Management Australian.

Support for decision-making: The idea of line of sight expressly demands that decision-makers at all levels are aware of both the business goals that are coming down from above and the asset performance, cost, and risk information that is flowing up from beneath them. Decision-makers are thus in a position to respond to the following questions:

- What kind of performance is being provided?

- Exactly what level of performance and value is desired?

As we know, nothing is flawless, and there will never be a truly ideal trade-off between performance, cost, and risk that can be identified. But the AM approach’s strength is that it recognises this imperfection and builds a continual feedback loop to alter the way assets are bought, managed, maintained, and disposed of to attain a reasonable approximation to optimal performance.

Some of the AM challenges

Unfortunately, not everything is perfect. AM presents a few difficulties. In today’s corporate world, AM is a vital and critical component of any successful operation. AM guarantees that all assets are appropriately bought, operated, and managed in accordance with industry standards and specifications, as well as with company policies and procedures. At every stage of a project’s lifecycle, from conception to completion, it is critical to ensure that asset management is properly structured and managed. However, issues faced by project managers who oversee the management, tracking, or simply monitoring of assets are numerous and varied. Here are some of the most common issues.

Choosing the right assets: Many business leaders are completely unaware of their company’s organisational structure and strategy. In such circumstances, deciding what assets to acquire becomes more difficult. The asset procurement teams can end up spending money on new assets without properly comprehending the necessity for the assets in question. When it comes to acquiring new equipment and software, the project manager can only make informed decisions if they know what assets they have, who else has them, what is currently in use, and how old or expired existing assets are. It becomes a challenge to gather all this information if the organisational structure does not support the right communication and documentation processes required for this decision-making step.

Acquisition of assets that are not under control: A traditional asset strategy that is focused on procurement is frequently responsible for the introduction of additional ungoverned assets into the business. We call ungoverned assets shadow assets. These are assets that are deployed within a firm without the permission of the project management or procurement department. This might result in the introduction of unchecked assets into the organisation, resulting in increased expenditures as well as security and compliance difficulties. This is a common challenge for organisations lacking a procurement department or a formal project management unit.

Assets that are cross-functional: Managing assets across functional departments (i.e., marketing, IT, HR, Finance, etc.) is a significant problem for organisations that want to run efficiently. This is because the various departments desire to use assets in a way that makes sense for their particular internal structure and often neglect the demands of other departments. Assets are frequently borrowed or shared by many departments, raising the likelihood of an operational disruption when an asset is required by more than one department but is already in use by another. It is here that a good work breakdown structure (WBS) identifying the asset usability is needed.

Public sector: A different set of challenges

As discussed before, we can see how the policies and practices of private sector organisations that practise AM are highly aligned: for example, the importance of AM to the organisation’s operations and profitability is clearly communicated throughout the organisation and is aligned to encourage highly effective management practices. However, there is a different layer of challenges for the public sector (i.e., government agencies and/or public organisations). The nature of the organisational structure, administrative and financial environment, as well as the limits imposed by other authorities, all contribute to the difficulty of applying AM concepts to the public sector. The following are some of the attributes of this environment that might make AM more difficult:

- Responsibilities for different areas of the public sector are dispersed among several government entities.

- Funding is frequently confined by prescriptive operations, restricting the freedom in which funds can be allocated and often distributing these to what senior management perceive to be the most critical areas of need.

- In addition, senior management does not often have access to adequate high-quality information to properly assess trade-offs and make funding allocation decisions, which makes it difficult to make successful asset needs judgements.

- Systems and databases are frequently standalone and/or the result of many changing trial versions, compounding challenges of system integration integrity, as well as the concerns of quality and timeliness of the data.

As a result of some of these issues, the implementation of AM inside public sector organisations tend to confront a variety of difficulties. We will touch on some of these challenges later in the book.

The role of the project manager

Project managers are the professionals who are required to handle all the AM information and deliver the projects that are related to it on time and within budget. These expectations can be difficult to meet for project managers due to the arduous task of managing enormous amounts of asset information while also ensuring that the most up-to-date information is made available to the appropriate individuals, at the most appropriate moment. For the project manager to be a valuable contributor to asset life cycle information, it is critical that the data transfer procedure be as easy as possible and they partake in this process from the start.

The project manager is in charge of allocating ownership for the AM plan’s implementation and ongoing administration. This includes coordinating all team procedures and tools training. They’ll also oversee keeping processes up to date as the project progresses. Project managers want a system that is safe, easy to use and deploy, and has the potential to scale to meet the demands of the organisation. The production, evaluation, release, distribution, and finding of information for asset projects are all functions that must be supported by an effective solution. To conclude, the solution must be capable of identifying data discrepancies and ensuring that they are corrected before it is too late.

Throughout an asset’s life cycle, there are a variety of functions that provide support for it. Now, let’s look at some of the main roles in AM as discussed in the following video.

Video: The main roles in asset management

This creative commons video was created by Martin Kerr, Principal and Founder of Structured Change and Certified Fellow in Asset Management.

In every organisation, it is essential to recognise and comprehend the interactions that take place amongst the primary roles that are involved in the process of AM. Martin Kerr describes the subsequent four responsibilities that are considered to have an effect on the capability of achieving effective AM. The ideas of AM and change management are brought together under the umbrella of structured change in order to provide businesses with excellent AM over the long term.

Other specific roles in asset management

According to the PMI, when it comes to AM, there are two key tasks to consider. It’s important to keep in mind that these tasks are assigned to roles and are not characterised as jobs. In small organisations, a single individual may fulfil both tasks, whereas in large organisations, these roles are distributed through the organisational structure and assigned to many of the existing positions. Keep in mind that the nature of the project, its size and context are everything. These tasks are defined by the following roles:

- An asset engineer oversees assets. Their role is guided by the collaboration within the project teams for identifying potentially reusable assets. Once the assets are identified, these are integrated in the WBS with existing assets into their projects. Assets may also be developed, evolved, supported, and retired by this role. If this happens then the role can also be referred to as a “re-use engineer”.

- An asset manager is a term used to describe someone who manages. Asset managers are in charge of leading, managing, and governing the purchase and use of assets inside the company. In certain times the project manager also operates as an asset manager.

Now, let’s summarise: AM’s objectives and good practices underpin service delivery, responsible stewardship, and risk management, all of which are essential for business success and are under the umbrella of project management processes. Organisations that adopt long-term AM as a way of doing business should be able to achieve good governance, sound long-term financial management, sustainable, equitable, and cost-effective service delivery, effective risk management, and effective asset function, capacity, and preservation management because of their investment.

Video: Asset management for directors

Project governance

When it comes to project management, organisations that use many projects to implement strategy, transform their businesses, improve their operations, or develop new products have come to rely on project governance as their primary method of project administration (Winter et al., 2006).

Multi-projects are becoming increasingly popular, and as a result, the need for an approach to provide clear administration and management structure is critical. Management literature has recognised the importance of structured, disciplined project management and the role governance has in creating value for their organisations. When it comes to project governance, we can explain it as the mechanism that ensures that project choices are consistent with the organisation’s governance rules and processes, therefore aligning with the organisation’s strategy. It also provides project managers and their teams with an organised framework for making choices, carrying out project procedures, and clearly defining their responsibilities throughout the project’s life cycle (from conceptualisation to completion). It also establishes the communication channels and approaches within the organisation and with the project team.

The project governance structure for the organisation is developed by internal stakeholders. The governance framework is developed to ensure that projects are completed successfully and in accordance with the aims and goals of the organisation. To establish a blueprint for project strategies, company directors and senior management tend to guide the development of the governance framework. Once finalised and established, project managers and their teams can follow this plan with confidence, knowing that they are tackling their project in the most efficient manner possible and in alignment with the organisation’s goals. However, there are companies that tend to outsource the development of the governance framework to external consultants. This is not as efficient as designing it in house. Outsourcing it is only recommended if business executives are required to devote their attention to other activities throughout the project life cycle.

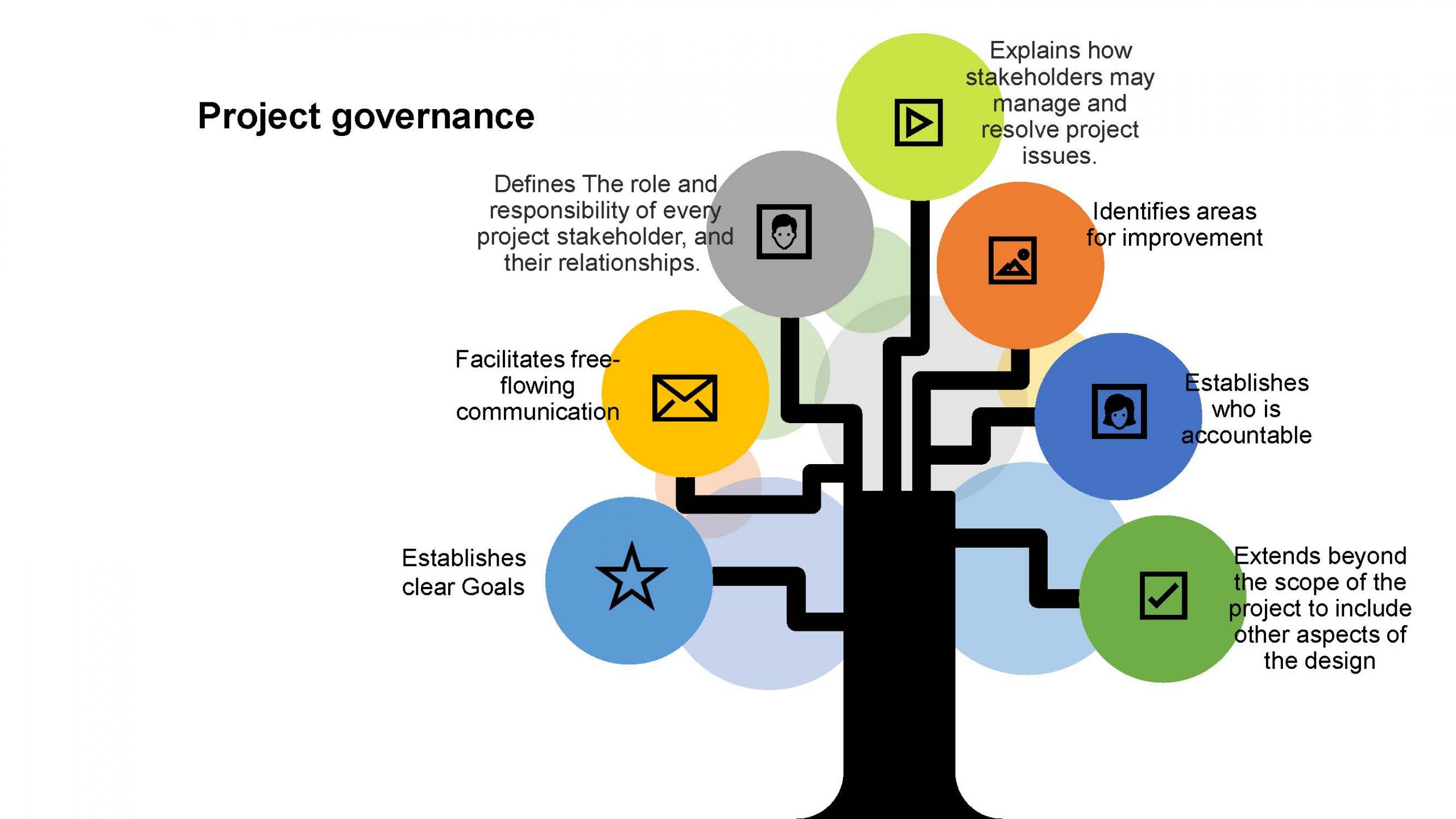

Project governance helps to make the procedures that take place throughout the project life cycle more understandable. Project governance also helps to clarify several critical issues, some of which are shown in Figure 2 below.

Overall, excellent governance is a key facilitator of effective portfolio and project management, as well as a critical component of successful initiatives. Governance is often concerned with who makes choices, how decisions are made, and whether cooperation is enabled, resulting in the definition of the governance framework within which decisions are made. There is no consistent approach to project governance – this will depend on the organisation’s structure and context in which they operate. Although there is a correlation between the governance resources and procedures needed, there is also a link with the complexity of projects. As the complexity of a project grows, the governance structure, resources, and organisational structure often grow in proportion to that complexity. Risk, organisational culture, and project maturity are all elements that influence the governance architecture.

Governance as a conceptual framework

The term governance is often used in conjunction with phrases such as government, governing, and control (Klakegg et al., 2008). When applied to organisations, governance is a framework for ethical decision-making and management action that is based on openness, accountability, and clearly defined responsibilities within the company (Muller, 2009). In the literature, the phrases “practical governance” and “academic governance” are often used interchangeably yet have distinct meanings. In practice and within this manual we will refer to the term “governance”.

When it comes to governance, there are two schools of thought. One school of thought holds that different styles of governance are required in different sub-units of an organisation. This perspective on governance appears to have been established by information technology managers, project managers, officials in government ministries, and academics who operate only in their respective fields of expertise. The organisation’s administration or anybody responsible for making choices and/or managing (controlling) the work of the organisation or its initiatives, in their opinion, is accountable for governance. Unlike other governance practices, each one acts independently of the others, and there is no unified philosophy of governance practice.

In the second school of thought, organisations such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2021), various Institutes of Directors (for example, the Australian Institute of Company Directors, 2019) and the agencies responsible for regulating stock exchanges have all contributed to the development of the concept. The governance process is viewed here as a single process with several components. We will further expand on the concept, characteristics, and models of governance later in Module 5.

Test your knowledge:

Key Takeaways

- AM is largely concerned with how an organisation allocates and uses resources, including money, people, skills, and information.

- Project managers adopt AM as a strategic approach to help them maximise the value of an organisation’s assets.

- Businesses are increasingly recognising the importance of excellent AM in ensuring the efficient delivery of services that fulfil the needs of their customers and other stakeholders, including government agencies.

- The right AM framework can improve the organisation’s processes and procedures and improve the governance of decision-making and capital approvals.

- Remember: AM is an integrative approach.

- Project governance is a framework within which project choices are made – a crucial component of every project.

References

Clash, T., & Delaney, J. (2000). New York State’s approach to asset management: A case study. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1729, 35-41.

Gordon, D. B. (1998). A strategic information system for hospital management [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Toronto.

International Organization for Standardization. (2014). Asset management — management systems, Guidelines for the application of ISO 55001, ISO 55002:2014(E), 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2724-3

Kerr, M (n.d). The Main Roles in Asset Management. Licencing: Creative Commons.

Klakegg, O. J., Williams, T., Magnussen, O. M., & Glasspool, H. (2008). Governance frameworks for public project development and estimation. Journal of Project Management, S1, 39.

PMBOK guide. (2021). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (7th ed.). Project Management Institute.

Marnewick, C., & Labuschagne, L. (2011). An investigation into the governance of information technology projects in South Africa. International Journal of Project Management, 29(6), 661–670.

Müller, R. (2009). Project governance. Gower Publishing, Ltd.

Winter, M., Smith, C., Morris, P., & Cicmil, S. (2006). Directions for future research in project management: The main findings of a UK government funded research network. International Journal of Project Management, 24(8), 638–649.