Module 8. Public governance in practice: A developing economy case study

Public governance in practice

Overview

In this module, we hope to make you aware of the fact that corporate governance and project governance are not the end-all and be-all of the discipline of governance. Public governance is equally important and a relatively emergent field. The key differentiating factor in public governance is that the wellbeing of all relevant stakeholders (users, interest groups, and society as a whole) must be equally considered while designing public investment projects. Therefore the center point to start planning this framework is our stakeholders.

By now, you are familiar with what constitutes good and effective governance. As we have seen, the governance of projects has emerged as a significant approach in the current project management literature. The PMI has recognised this as a formal approach and more and more organisations are on the road to adopting governance as a formal method to achieve their goals and objectives.

Private as well as public organisations embark on projects with the greatest of intentions to see them through to completion. However, in the public sector and for emerging countries, many projects tend to fail due to governance and management challenges within their system. For the economic development of emerging countries, effective governance is required for public-private development initiatives to succeed. Traditionally, project results have been assessed in terms of finishing them within the tradition of the iron triangle: scope, time and money. However, this no longer seems to be the case. In the seventh edition of PMBOK (2021), project evaluations are increasingly being extended to governance, to also include their capacity to fulfill strategic goals over long periods of time.

Reading: Success and failure rates of eGovernment in developing/transitional countries

Have a look at some of the project failure statistics presented in the following article, “Success and failure rates of eGovernment in developing/transitional countries” by Richard Heeks. The article suggests that there is enough evidence to suggest that more than one-third of e-government programmes in developing and transitional nations are unsuccessful completely, that another half are unsuccessful partially, and that around one-seventh are successful. Please click the link below.

With regard to public projects executed in long-term development environments, unfortunately there is a long-term record of project failure. Complexity, corruption, strong closed networks and the various political uncertainties are quite prevalent in emergent countries and often projects are derived, designed and planned from their own specific social and environmental conditions, ultimately turning into unmanageable projects. One of the characteristics of having good governance in place is the ability to guide these types of projects through a variety of uncertainties and unanticipated outcomes. Fortunately, public governance is at the top of the agenda for implementation and practice in many emergent countries (PMBOK, 2021).

Reading: Governance frameworks for public project development and estimation

The paper published by PMI on “Governance frameworks for public project development and estimation” by Klakegg et al. (2008) highlights some unique characteristics of governance in the public/government sector. Please click the link below and review these characteristics.

Adapting project management approaches for public sector initiatives is important. It is critical for project managers to understand the project environment, particularly as this is often unique to the public sector and their key stakeholders (i.e., decision-makers). It is therefore crucial that project managers aim for a governance framework suitable to this environment, one that enables transparency and accountability since the public sector has a significant and widespread impact on the lives of locals in emerging countries, as well as on the operations of the private sector aiding the development of these nations. Because of this, we feel it is critical that you get familiar with the nature of these types of projects as well as the governance structures that will be necessary for success.

References

OECD. (2021). Government at a glance 2021. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en

PMBOK guide. (2021). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (7th ed.). Project Management Institute.

The following case study sheds light on some of the key aspects faced in developing economies. This case is a contribution from John Connell who is currently working in collaboration with other researchers on the project titled “Smallholder farmer decision-making and technology adoption in southern Laos: opportunities and constraints” at the College of Business, Law & Governance, JCU.

Case Study

GOVERNANCE CASE: USING GOVERNANCE TO ACHIEVE IMPROVED SERVICE-DELIVERY IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES (Lao Peoples Democratic Republic).

By John Connell

Case outline

‘Governance’ can often appear to focus on the application of systems that constrain undesirable behaviours. While this is certainly one of its functions, ultimately good governance should result in a range of outcomes that benefit the population. In low income and developing economies, the establishment of ‘good governance’ includes the improvement of delivery of various services (e.g., health, education etc.) aimed at enhancing livelihoods and establishing more robust local economies. Conversely then, setting pragmatic outcome targets (e.g., increased agricultural production), can provide an entry-point for establishing good governance mechanisms which can then be applied more generally and have broader implications.

This case study provides a brief overview of Lao PDR, its political and economic structures and processes. It then introduces three external initiatives provided by foreign aid projects designed to enable good governance. They each supported practical activities, (e.g., construction of local infrastructure, increased agriculture output, etc.) which invoked application of good governance to achieve the desired pragmatic outcomes, thereby simultaneously demonstrating the benefits of good governance and strengthening the institutional mechanisms, enhancing sustainability and replication.

These initiatives were implemented in three contexts: a United Nations Development (UNDP) Program; bi-lateral agriculture development project; and an NGO-led development project, which took place at three levels of government – national, ministerial and provincial, respectively. The author was involved in the first of these in a limited way, and was directly involved in the design and implementation of the second two. These both remain works in progress, but have had tangible results both in terms of pragmatic outcome and acceptance of improved governance norms.

In this discussion, good governance will be based on the elements as defined by the UNDP (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia, n.d.) and the Pacific; 1) Participation, 2) Rule of Law, 3) Transparency, 4) Responsiveness, 5) Consensus Oriented, 6) Equity and Inclusiveness, 7) Effectiveness and Efficiency, 8) Accountability (refer to figure 20 ).

Lao PDR context for governance

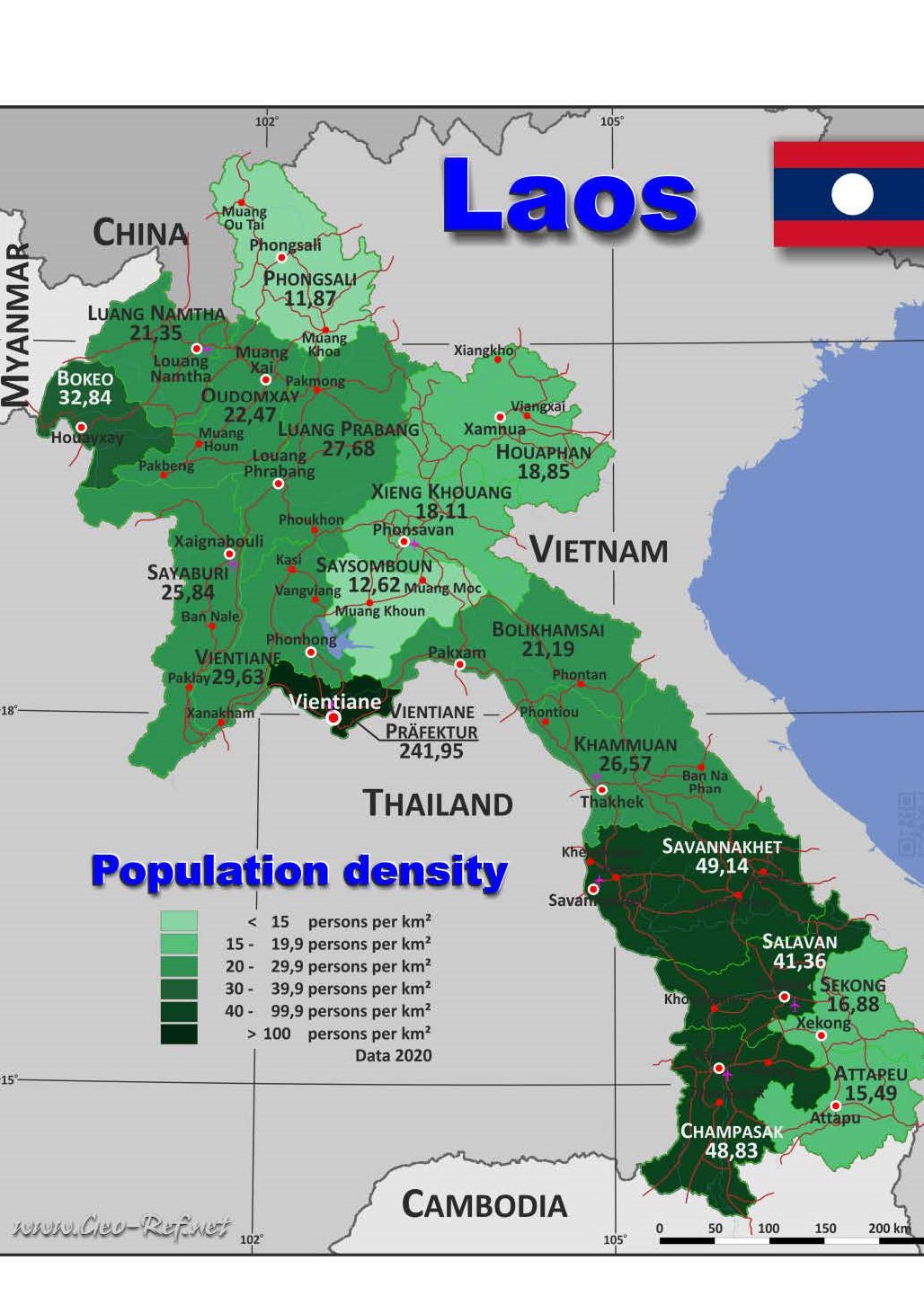

Lao PDR is the only landlocked country of South-East Asia, bordered in the north by Myanmar and China, in the east and west by Vietnam and Thailand, and in the south by Cambodia (see figure 21). It has a low population density (pop 7.5 million). With almost three-quarters of the country blanketed in mountains and wooded hills the topography has limited the development of extensive agriculture to the few river valleys where cultivation of paddy rice developed. The Mekong River forms most of the border with Thailand and rivers have historically provided transport routes and food sources (fish), and in recent times increasingly a source of hydro power. Between the mountain chain along the eastern side of the country and the Mekong River, there are three high plateaus: Xiangkhouang, Khammouan, and the Bolovens. The Bolovens Plateau in the south near Cambodia has highly fertile volcanic soils where the production of horticulture crops including coffee and rubber have developed. While hydroelectricity and mining are playing an increasing role in the national economy, about 70% of the population remain directly engaged in, or dependent on agriculture (Asian Development Bank, 2018).

The development of good governance in Lao PDR has taken place within a dynamic context. Laos as it was then known, had side role in the Vietnam war hosting parts of the Hochiminh trail, which resulted in it being subjected to extensive bombing. After years of fighting, in 1973 the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP) succeeded in forming joint provisional government with the Royal Lao Government. Following several rebellions, in 1975 the LPRP took control of the country. The country at this point had a population of just over 3 M and was still essentially a rural economy of subsistence farmers with a few urban centres and a limited bureaucracy. The dominant factors that guided life were a Buddhist culture, and family or social connections, in which loyalty, respect and reciprocity dictated behaviour. In effect, any introduction of governance norms would be replacing these close-knit kinship and social ties; an historical state of affairs within which formal governance structures would have been perceived to have limited utility.

On taking power the LPRP, generally known as the Party, introduced several common socialist mechanisms that included collective farming and central planning. Collectives were introduced (1978) and then abandoned (1983) judged as being unsuitable in the still very rural context of Lao PDR. A far bigger experiment was undertaken in 1989 with the institution of the New Economic Mechanism (NEM) that opened the economy to private sector activity. Internally there have been major shifts in power, beginning with a process of de-centralization to the provinces in the ‘80s, re-centralization in 1991, and finally the sharing of power beginning in 2000, with what is called de-concentration.

External influences, which to a large degree were determined by sources of economic support to Lao PDR, have shifted from its socialist partners (Russia and Vietnam), to foreign donor development aid or largely Western official development and aid (ODA) to growing investment by Chinese entities in more recent years. The country itself was essentially isolated from Western engagement until construction of the first cross-Mekong Bridge (1994). Through all these periods of development, the Party retained control of government as a single party state. The Central Committee with its Politburo are the highest policy decision making authorities and these set all policy directions. Membership of the Party can be gained only by invitation. The National Assembly, the Party’s executive and law-making body, is formed by a generally election but only from candidates selected by the Party. Altogether this provides limited opportunity for any open review of government policy. At the same time, the major shifts in policy and power as described above, show that significant change and development is highly constrained.

Positive changes in governance have taken place across the board with respect to the rule of law, equitable service delivery, and general participation with civil societies that have led to tangible improvements economic and social life. This has occurred as new and younger persons with higher educational backgrounds are brought into the Party, and with the recognition by the Party itself that good governance is necessary to foster economic development and for Laos to engage more broadly internationally (Slater & Keoka, 2012).

Good governance, as defined by the Government of Laos (GoL), has four pillars: 1) people’s representation and participation; 2) public service improvement; 3) rule of law, and, 4) public financial management (Slater & Keoka, 2012). These overlap with those defined by UNDP but noticeably exclude transparency and accountability. Despite these improvements, Lao PDR is still regarded as having poor international rankings for transparency, ease of doing business and corruption (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022).

#1 SPECIFIC INTERVENTION – DECENTRALISED PLANNING FOR PUBLIC WORKS

As a requirement of the Lao government, all ODA projects in Lao PDR work through and with the appropriate government agency: agriculture, health, education etc. These projects have all attempted in various ways to improve effectiveness and efficiency of the agencies they partnered with. Beginning in 2012 the UNDP through its Governance and Public Administration Reform (GPAR) (United National Development Programme, n.d.). National governance and public administration reform programme secretariat support project program brought a focus on governance specifically. This was composed of serval components of which the District Development Fund (DDF) (O’Driscoll, Oudomsine & Bounyakheth, 2021) will be examined in more detail here.

The DDF provided funds for ‘block grants’ of, on average, about $27,000 to fund projects identified and then managed by District agencies. In working towards project objectives, Districts conducted participatory planning exercises with village communities and then generated a shortlist of projects which were then submitted these for approval. These typically funded construction of small infrastructure projects such as classrooms, water supplies, paths and small bridges, etc. These were overwhelmingly successful in delivering the stated infrastructure within budget.

The DDF initiative in its identification of projects from the bottom-up essentially put into action governance elements of ‘participation’ and ‘responsiveness’. As a result, the DDF has demonstrated that local administrations could be effective in the management and delivery of small investments (as distinct from large externally or centrally managed projects). The practical nature of the public works activities required Districts to comply with a degree of ‘transparency’ in use of funds, and to accept ‘accountability’ for their performance in the delivery of the projects.

The extensive rollout of DDF across 66 of the 148 District of Lao PDR was ambitious with a few glitches along the way, but demonstrated the above attributes governance in a substantial manner, not as a special case or as a pilot. In a broader sense the DDF provided to counter balance to the negative lessons of de-centralization in the ‘80s. These lessons were taken to heart and in the later years of the program. The Lao government co-funded DDF to expand its application, and more generally adjusted its planning approaches to provide a greater role for Districts to determine development objectives (O’Driscoll, Oudomsine & Bounyakheth, 2021).[8] The DDF has thus led to profound and sustainable changes.

#2 SPECIFIC INTERVENTION: ENHANCING SERVICE DELIVERY – AGRICULTURE EXTENSION

The key agency responsible for agriculture is the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). The implementing arm of MAF at the District level are the District Agriculture and Forestry Offices (DAFO) with the Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Offices (PAFO) providing a coordinating role across its Districts. The effectiveness of the DAFO was regarded as poor both technically and in terms of its working approaches.

As ODA began to play a significant role in the still rural Lao PDR, many of the projects included components for agriculture development. These focussed on the introduction of improved production practices for smallholder farmers (improved production practices commonly include use of inputs such as new rice varieties and fertilizer; vaccination of livestock against disease; new cash crops such as maize, coffee, etc.) and the training DAFO technical staff in the use of more effective extension approaches. These projects have been successful in terms of demonstrating improved models of production and in real production increases by smallholder farmers. Despite their success once project funding ended these activities were not continued or expanded to new areas.

Primarily, like more government services the DAFO received minimal budgets that did not cover even basic operating costs to mobilise field staff. Apart from the general scarcity of public funds, there was an unwillingness to fund the DAFO due to the beliefs that: (a) staff were not effective; and (b) there was no guarantee the DAFO would use the funds to carry out intended work.

In addition, all the ODA projects operated in parallel to the existing government structures through their own Project Management Units (PMUs). These retained control of all project planning and funds, and reported back to the donors. As a result, while field staff gained experience, no management skills were conveyed to the administration sections of the DAFO and there was little lasting capacity building.

The Department of Agriculture Extension and Cooperatives (DAEC) is the agency within MAF that has oversight for the operation of agriculture extension. To address negative perception of the DAFO and justify fund allocation, a team from College of Business Law and Governance (CBLG) with DAEC designed the project Enhancing District Delivery and Management of Agriculture Extension in Lao PDR (2013-2016) (Connell, Case, & Jones, 2017). This aimed to demonstrate that it was possible to improve DAFO performance, build management skills capacities in a sustainable way and, thereby, justify creation of a mechanism for funding activities internally within the GoL system (as opposed to reliance on external ODA).

The key elements of the design were: (a) the DAFO to select an existing agricultural activity with potential for commercial levels of production, and to frame their plans for its development across the whole District. By focusing on gross output, rather than on improved yields and techniques, the project hoped to align with District economic goals and thereby engage the District Governor; (b) provide DAFO limited operating funds ($5000/yr) for a guaranteed period of 3yrs; (c) devolve all management decisions to the DAFO.

The Project developed an Extension Management System (EMS) to provide pragmatic management tools for the DAFO which included: planning, fund management, delivery approaches, and reporting. The project was managed by staff at DAEC supported by the international research team, with reporting meetings held at the provincial level each six months. In these meetings, DAFO from each district within the province reported their progress, and the project team could ‘advise’ on next steps. Critically these meetings provided the context to engage the key District authorities outside of the agriculture sector, i.e., the District Governor’s Office and the District Planning and District Finance Offices. It was these entities who, in the long run, would decide on fund allocation for the DAFO. Thus, by involving them at an early stage, it would ensure they were informed and understood the work and be invested in it to some degree.

The project operated in 5 districts of two provinces that covered a range of economic and agro-economically environments, and worked with products that ranged from rice (a regions staple) to livestock (poultry) and horticulture (vegetables and coffee). Capacities of DAFO staff in these districts varied greatly. Staff from two of the DAFO had experience working in earlier related projects, whereas staff in the three other DAFO had quite limited capacity. Within the four seasons (2013-2016) during which the project operated, each of DAFO achieved significant increases in production and the smallholder farmers involved were able to shift from small-scale toward commercial production of commodities in their respective Districts. These results were exceptional compared to many contemporary agricultural projects. The production outcomes were all the more unusual insofar as the project team was not constantly on the ground in the districts and did not provide any special training to the DAFO staff. The project opportunity to influence performance had been limited to the framework provided by the EMS and the six-monthly reporting meetings.

The operation of the DAFO using EMS led to dramatically improved ‘effectiveness’. The EMS itself provided pragmatic tools for management, empowered staff and enabled them to operate with autonomy. Within this new regime, the DAFO staff had to report not only on their activities as was common in the past, but also their progress towards targets identified and specified in 3-year plans. In this way, over the course of the project they began to adopt a results-orientated rather than activity-orientated approach to delivery. This was reinforced by the fact that they were reporting to authorities (Governor, Planning and Finance) who were less interested in the details of agriculture production than the gross outputs being achieved.

Other aspects of governance had played a role as well. The role of product selection by the DAFO (participation) gave them a sense of ownership of the work. The reporting of results gained against the targets in their plans (transparency) to district authorities brought them recognition, but also a degree of ‘accountability’.

Interviews with District administrative staff toward the end of the project confirmed that the DAFO were beginning to be seen as being able to perform effectively, to generate results and thus, worthy of being funded. However, these ideas had not been fully consolidated by the time the project ended and did not align with the 5-Year GoL planning cycle. Thus, the following dynamic remains somewhat speculative:

Allocation of regular and significant funding to DAFO, would engender internal demand for improved governance, that don’t apply in the same way as when ODA funds are being applied. The domestic funding of DAFO would bring with them expectations of results, (effectiveness, and accountability) and scrutiny of the use of those funds. Systems for monitoring of both production results and fund use come to be required (transparency).

While the EMS has been through several reviews within MAF, it has not been taken up for general application amongst the many other projects in the sector. Application of EMS would require a more broadly based application, as was the case for the DDF. It is still being applied within several NGO projects, and under consideration to be used by several broader bi-lateral aid projects as a means to confer sustainability to extension in a systemic way.

#3 SPECIFIC INTERVENTION: RATIONALISING LOCAL TRADE OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS

Agriculture products remain to a large extent grown by smallholder farmers with farm sizes around 1 – 2 hectares. This brings with it inherent variability in terms of quality of the products produced, whether this be rice, chili or coffee. It is also involving the product moving through the hands of various middlemen before it reaches major traders who then ship it inter-province or cross-border (Vietnam, Thailand, China).

Traders face various speed bumps as they ship any of the products to the end markets. The first of these occurs in assembling necessary paper work with the various offices at the Provincial level, each having their own requirements and fees. These typically will include the Departments of Agriculture; Commerce and Trade, and Transport. Time to navigate these procedures can run to days, which then affects product quality, weight-loss and other forms of degradation. En route to its destination, vehicles pass checkpoints for paperwork inspection. Inspection fees (informal) must be paid irrespective of the paperwork was in order or not.

The effects of these procedures are felt in different ways. The additional costs for traders directly result in depressing prices that farmers receive. When traders resort to circumventing the procedures to save themselves costs, the shipments become ‘informal’. This results in Lao products missing recognition and branding once they arrive across the border in Vietnam, Thailand, China. Loss of legitimate fees collected, of course means a loss of scarce revenue for the state. In extreme cases traders have suffered complete loss of shipments and, in others, traders have given up on a particular trade as too costly or risky, thereby denying farmers a market outlet. Thus, impacts can be felt both by the farmers and in legitimate trade being undermined.

These issues are well recognised. Various Prime Ministerial (PM) orders and decrees have been issued to facilitate trade. The order No 02/PM (01/02/2018), subsequently reinforced by No 12/PM (16/10/2019) and No. 03/PM (21/01/2020) (Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2018), require that: trade documents should be processed using a one-stop-shop approach; that fees for export license be reduced by 50%; border checks be streamlined; and finally internal checkpoints be abolished. Across the country these have been implemented quite variably particularly in the areas that have remained outside the main corridors of development; as a legacy of earlier decentralisation; a desire to continue old fee collections; or because of inefficiencies in implementation. All these failings resonate with aspects of poor governance.

These failings and inefficiencies were very much to the fore when it came to designing a project (2019) in the northern province of Bokeo, where Plan International an International NGO was supporting a small Lao NGO, MHP (Maeying Huamjai Phattana” or, women mobilising for development) to develop the Rural Enterprise for Agriculture Livelihoods (REAL) project.

The core of the design for the REAL project included two activities to directly support farmers’ income: (a) improved production practices; and (b) engagement in the value-chain. However even with success in these, incomes could easily be undermined by poor trading practices. Thus, a third element was added, to achieve better “trading practices”. This is an ambitious activity for a small NGO to attempt as it has very limited influence to change the roles of the various Departments noted above. It could also be seen by certain powerful stakeholders to be ‘meddlesome’ insofar as it might confront vested interests.

To be effective in bringing about some degree of change in trade practices and to avoid confrontation, the strategy for this component involved: (a) engaging a senior entity from the central level of government who would bring clear oversight of all relevant laws and regulations – such a person would also command some respect from the Provincial authorities; (b) conducting ‘annual reviews’ of the trade procedures and noting any departures from national regulations and costs that this incurred for provincial trade. Holding the reviews annually meant that the various local agencies would know that if nothing was achieved it would turn up again the following year. And here, the involvement central entities would add additional ‘transparency’ to the issues that might otherwise be avoided or contested if discussed within Provincial confines only.

As the entity based at the central government level, REAL formed a partnership with a team at the National Agriculture Research Institute (NAFRI) which also had support from the Prime Minister’s Office to assess and facilitate trade streamlining nationally. They saw that the REAL project would provide an additional site and support to enable change.

The province had already formed a Provincial Trade Facilitation Committee aimed at rationalising trade procedures to follow new national directives. This was composed of the various Departments and chaired by a Deputy Provincial Governor who would thus exercise authority over the Department and make binding decisions. This has already acted to apply the PM directives already, mainly in terms of introducing one-stop-shops for trade documents and reducing the cost and time taken for processing these. These changes are directly under its control at the Provincial level.

The first of the annual trade reviews was conducted in February 2022 with the workshop following in March The March workshop took place as an activity of the Provincial Trade Facilitation Committee, chaired by the Deputy Provincial Governor. The finding of the review were that procedures and costs at the Provincial level were indeed streamlined and costs reduced. These costs can amount to 1-1.5% of the value of a shipment. However, within the districts the PM directives for streamlining trade was not consistently applied, with some district official stating they were not aware of the new procedures. As a result, up to four internal check points still operated, collecting fees or charges irrespective of whether documentation was in order or not. These informal fees can add up to another percentage point or more on the cost of trade, as well as causing delays. As a result is was directed in the workshop that (a) all districts conduct a review of their procedures and (b) identify how new trade regulation can be put into practice. In this way the initiative for change will be driven by the relevant Provincial Departments themselves.

The benefits of achieving good governance for the trade of agriculture products have profound implications. In effect in would see the ‘rule of law’ being applied. The way that REAL has worked to progress towards this is by achieving a degree of ‘transparency’ through enlisting external partners (NAFRI), conducting public review of findings and building consensus through workshop reporting and discussion.

Reflections

Good governance has evolved in the developed economies over many years and, arguably, has been forced upon those economies in response to gross failures in the past. As suggested early in this paper, when the social and economic networks are regionally confined and limited, matters of process and regulation are not so important. Once the society/economy reaches a point where the volume of interactions increases, and where these interactions begin to take place outside of familiar networks, then the need for governance becomes more necessary. It would seem that Lao PDR is now well on the way to understanding the need for and embracing the ideals of good governance.

The importance of good governance is now recognised by the government of Lao PDR, so that it can achieve a more efficient and productive economy and society. While the generic ‘good’ of governance is recognised, these can be resisted due to entrenched practices or disruption of personal benefits. Recognising the ‘good’ is not enough.

In this way it has been useful for external agencies to play a role with relevant Lao entities who contribute both strategies, and funds. The DDF is perhaps the most successful of the initiatives discussed in this case study. The support of external funds for concrete and needed local infrastructure provided a common goal. The DDF procedures brought ‘transparency’, and the outcomes demonstrated ‘efficiency’ enabled a more de-centralised decision making and implementation process to be demonstrated. Because the activity was conducted on such an extensive basis, this brought a degree of normalcy with it and has resulted in the government continuing to provide its own funding and enabling planning and implementation from lower levels of government. This has brought with it elements of good governance necessary to made this function.

While the other two initiatives cannot claim the same degree of impact primarily, they still provided demonstration of the efficacy of good governance. The EMS procedures enabled the DAFO to operate at far higher level of effectiveness (effectiveness). Their report on results and fund expenditures put them on the pathway towards justifying continued funding. This would have created a further internal demand that the DAFO produce results (accountability) and use funds for the stated purpose (transparency). This may yet be recognised if the EMS continues to be applied more extensively in the manner that DDF was.

Finally, the initiative to achieve streamlined trade employed a strategy of ‘transparency’ so that well known challenges could be recognised and addressed more openly. By engaging entities from outside of the province this helped to build a consensus that would overcome inertia and compel change.

All three of these initiatives have independently used a similar strategy of posting concrete or pragmatic and agreed outcomes which then require various elements of good governance to be applied to ensure their success. This can demonstrate the value of the good governance elements but, in addition, the initiatives need to be applied widely enough to be accepted. The EMS and Trade initiatives outlined above were still at a proof-of-concept stage at the time of writing and broader application will be needed to establish practices and gain recognition.

Case Study References

Asian Development Bank. (2018). Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Agriculture, natural resources and rural development sector assessment, strategy and road map. https://www.adb.org/documents/lao-pdr-agriculture-assessment-strategy-road-map

Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2022). Country report: Laos. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/LAO

Connell, J., Case, P., & Jones, M. (2017). Enhancing district delivery and management of agriculture extension in Lao PDR. Australian Center for International Agriculture Research (ACIAR). https://www.aciar.gov.au/project/asem-2011-075

Lao People’s Democratic Republic. (2018). Prime Minister’s Office: order on improvement and coordination mechanism for running business in Lao PDR. http://db.investlaos.gov.la/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/pm02_order-db_v-eng.pdf

Slater, R., & Keoka, K. (2012). Trends in the governance sector of the Lao PDR. Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. https://www.eda.admin.ch/deza/en/home/publikationen_undservice/publikationen/alle-deza-publikationen.html/content/publikationen/en/deza/diverse-publikationen/study-lao-pdr

United National Development Programme. (n.d.). National governance and public administration reform programme secretariat support project https://www.la.undp.org/content/lao_pdr/en/home/projects/national-governance-and-public-administration-reform-programme-s.html

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. (n.d.) What is good governance? https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/good-governance.pdfO’Driscoll, G., Oudomsine, T., & Bounyakheth, B. (2021). The district development fund of Laos. United Nations Capital Development fund. https://www.uncdf.org/article/7171/the-district-development-fund-of-laos