Overview

Successful companies normally develop strategic direction, including goals and objectives. To achieve their strategic direction, organisations need to formulate and implement specific actions or programs, e.g. to increase sales it may be proposed to open a new sales office and warehouse in a new market area, or to improve the quality of product it may be proposed to procure and install new production equipment.

According to Gardiner (2015), “The number of companies turning to project management as a way of adding value to their bottom line continues to grow, with projects increasingly viewed as ‘building blocks’ in the design and execution of … strategies”. Gardiner goes on to argue that there is a strong link between strategic intent, project conception, and project selection. For example, in the automotive industry, it is a common practice to update models annually to remain competitive. This may involve projects to upgrade production facilities to enable new processes, reduce costs, adopt new technology, or manufacture new products for new markets. It is common, during annual Christmas/New Year shutdown periods, for vehicle manufacturing plants to implement intensive projects in a short time frame to remove existing facilities and install a new system or equipment to be operating in time for the resumption of work.

Other organisations seek to implement their strategies by winning new business to build products for clients. For example, a defence electronics and systems company may develop a project to design, test, manufacture, and supply armoured vehicles required by the Australian Defence Force. Some projects may be a means of developing new capabilities for the company. For example, a communications equipment manufacturer may use a strategic project bid to build a satellite communications device as a vehicle to develop this new technology capability.

Projects commit an organisation to expend significant levels of resources of all types. To ensure that the projects selected are in accordance with the strategic direction, the approval process normally goes up through higher levels of management authorisation. Apart from approval to proceed with the project, such authorisation should also specify the basis for an authority to cease a project.

The structure of the organisation also plays an important role in shaping the success of projects. The structure can impact how well a project is managed – or how well an ineffective project is also managed. Mostly three organisational structures can be identified in project-oriented businesses: 1. Functional, 2. Matrix, and 3. Project focused. The following table provides a summary of some key advantages and disadvantages of these structures.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Functional | Commitment to function

Good for function-specific projects (i.e., a marketing campaign) Works well in predictable environments |

Creates silos

Allegiance to own department Slows down cross-functional work Limited communication Customers are not the primary focus |

| Project | Exclusive focus on projects

Dedicated resources The project manager retains control Fast decision making |

Can be expensive

Project focused rather than strategically focused Shorter contracts/staff uneasy about project end |

| Matrix | Suited to dynamic environments

Mix of functional and project structures Co-ordinated work Allocates scarce resources |

Conflicted reporting

Conflicted workloads Sharing resources |

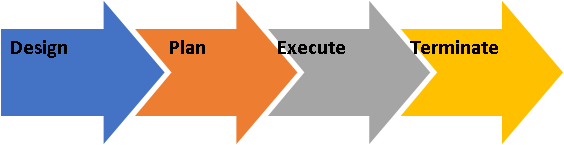

Now, let’s look at the Project Life Cycle.

Project Life Cycle:

5 Basic Phases of Project Management

Project Management Institute, Inc. (PMI) defines project management as “the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to a broad range of activities to meet the requirements of a particular project.” The process of directing and controlling a project from start to finish may be further divided into 5 basic phases:

1. Project conception and initiation – Design

An idea for a project will be carefully examined to determine whether or not it benefits the organisation. During this phase, a decision-making team will identify if the project can realistically be completed.

2. Project definition and planning – Plan

A project plan, project charter and/or project scope may be put in writing, outlining the work to be performed. During this phase, a team should prioritise the project, calculate a budget, as well as schedule and determine what resources are needed.

3. Project launch or execution – Execute

Resources’ tasks are distributed, and teams are informed of responsibilities. This is a good time to bring up important project-related information.

4. Project performance and control – Execute Control

Project managers will compare project status and progress to the actual plan, as resources perform the scheduled work. During this phase, project managers may need to adjust schedules or do what is necessary to keep the project on track. In some cases, this phase is integrated with the execution phase.

5. Project close – Terminate

After the project tasks are completed and the client has approved the outcome, an evaluation is necessary to highlight project success and/or learn from project history.

It is important to note that the project manager and project team have one shared goal: to carry out the work of the project for the purpose of meeting the project’s objectives. Therefore, it is critical to identify what happens in each of these phases. Let’s look at these in more detail.

Initiation Phase

During the first of these phases, the initiation phase, the project objective or need is identified; this can be a business problem or opportunity. An appropriate response to the need is documented in a business case with recommended solution options. A feasibility study is conducted to investigate whether each option addresses the project objective and a final recommended solution is determined. Issues of feasibility (“can we do the project?”) and justification (“should we do the project?”) are addressed.

Once the recommended solution is approved, a project is initiated to deliver the approved solution and a project manager is appointed. The major deliverables and the participating work groups are identified, and the project team begins to take shape. Approval is then sought by the project manager to move onto the detailed planning phase.

Planning Phase

The next phase, the planning phase, is where the project solution is further developed in as much detail as possible and the steps necessary to meet the project’s objective are planned. In this step, the team identifies all of the work to be done. The project’s tasks and resource requirements are identified, along with the strategy for producing them. This is also referred to as “scope management.” A project plan is created outlining the activities, tasks, dependencies, and timeframes. The project manager coordinates the preparation of a project budget by providing cost estimates for the labour, equipment, and materials costs. The budget is used to monitor and control cost expenditures during project implementation.

Once the project team has identified the work, prepared the schedule, and estimated the costs, the three fundamental components of the planning process are complete. This is an excellent time to identify and try to deal with anything that might pose a threat to the successful completion of the project. This is called risk management. In risk management, “high-threat” potential problems are identified along with the action that is to be taken on each high-threat potential problem, either to reduce the probability that the problem will occur or to reduce the impact on the project if it does occur. This is also a good time to identify all project stakeholders and establish a communication plan describing the information needed and the delivery method to be used to keep the stakeholders informed.

Finally, you will want to document a quality plan, providing quality targets, assurance, and control measures, along with an acceptance plan, listing the criteria to be met to gain customer acceptance. At this point, the project would have been planned in detail and is ready to be executed.

Implementation (Execution) Phase

During the third phase, the implementation phase, the project plan is put into motion, and the work of the project is performed. It is important to maintain control and communicate as needed during implementation. Progress is continuously monitored and appropriate adjustments are made and recorded as variances from the original plan. In any project, a project manager spends most of the time in this step. During project implementation, people are carrying out the tasks, and progress information is being reported through regular team meetings. The project manager uses this information to maintain control over the direction of the project by comparing the progress reports with the project plan to measure the performance of the project activities and take corrective action as needed. The first course of action should always be to bring the project back on course (i.e., to return it to the original plan). If that cannot happen, the team should record variations from the original plan and record and publish modifications to the plan. Throughout this step, project sponsors and other key stakeholders should be kept informed of the project’s status according to the agreed-upon frequency and format of communication. The plan should be updated and published on a regular basis.

Status reports should always emphasise the anticipated end point in terms of cost, schedule, and quality of deliverables. Each project deliverable produced should be reviewed for quality and measured against the acceptance criteria. Once all of the deliverables have been produced and the customer has accepted the final solution, the project is ready for closure.

Closing Phase

During the final closure, or completion phase, the emphasis is on releasing the final deliverables to the customer, handing over project documentation to the business, terminating supplier contracts, releasing project resources, and communicating the closure of the project to all stakeholders. The last remaining step is to conduct lessons-learned studies to examine what went well and what didn’t. Through this type of analysis, the wisdom of experience is transferred back to the project organisation, which will help future project teams.

Text Attributions

This section contains material derived and remixed from the following sources:

- Project Management – 2nd Edition by Adrienne Watt is licensed under CC BY (Attribution) 4.0 International License

- Project Management by Merrie Barron and Andrew Barron is licensed under CC BY (Attribution) 3.0

- Project Management From Simple to Complex by Russel Darnall, John Preston, Eastern Michigan University is licensed under CC BY (Attribution) 3.0