3 A Naturalist’s Holiday by the Sea

Trisha Fielding

The members of the Great Barrier Reef Expedition received an enthusiastic welcome upon arrival in Australia, when the Ormonde docked at Fremantle. They were also greeted warmly as they called at Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney, before finally arriving in Brisbane on 9 July 1928. Mattie Yonge, the expedition’s medical officer, described the group’s reception in Australia as “such that might have been given to royalty”.[1] A veritable who’s who of Brisbane’s scientific community were invited to welcome the group at a gala dinner the following evening, indicating how important the expedition was for Queensland. Guests included members of the executive of the Great Barrier Reef Committee, the Commissioner for Public Health, the Government Botanist and the Director of the Queensland Museum, along with a number of senior university academics. Also present was Mr F.W. Moorhouse, of the Queensland Education Department. Moorhouse had been seconded to the Department of Harbours and Marine by the Premier, and was to join the initial expedition party to Low Isles.

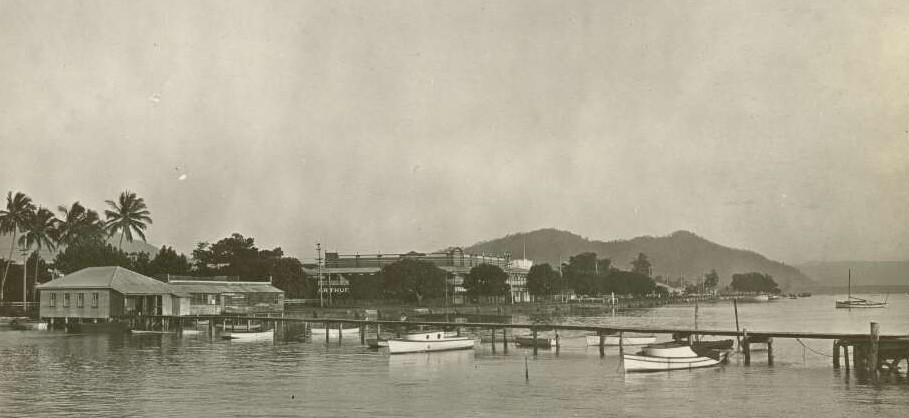

The following day, Yonge’s group departed Brisbane and travelled by rail to Cairns, a journey that took two and a half days. The expedition members were accommodated at A.J. Moran’s Strand Hotel for a couple of days while the last items of necessary equipment and provisions were purchased. One of the many publications that resulted from the expedition was A Year on the Great Barrier Reef, which was written by Yonge and intended for a general audience. In it, Yonge wrote that thanks to A.J. Moran, “we gained our first introduction to the glories of the tropical rainforest in the foothills behind the city.”[2]

It was while they were staying at Moran’s hotel that Yonge’s team experienced their first adventure in north Queensland. Moran took the Yonges and several others from the expedition party out to Freshwater by car to show them the rainforest.[3] Although Freshwater is now a suburb of Cairns, at the time of the Yonges’ visit much of the area was still relatively untouched by development. At one stage Moran was negotiating a steep incline when the car slid off the dirt track into a creek. Fortunately, no one was injured, and after failing to push the car out, the group walked two miles to the nearest cane farm. Their next challenge was to try and explain to the Italian farmer there (who spoke no English) that they were stranded. Horses were loaned to pull the car out of the creek and the group eventually arrived back in Cairns that night, none the worse for their rainforest adventure.

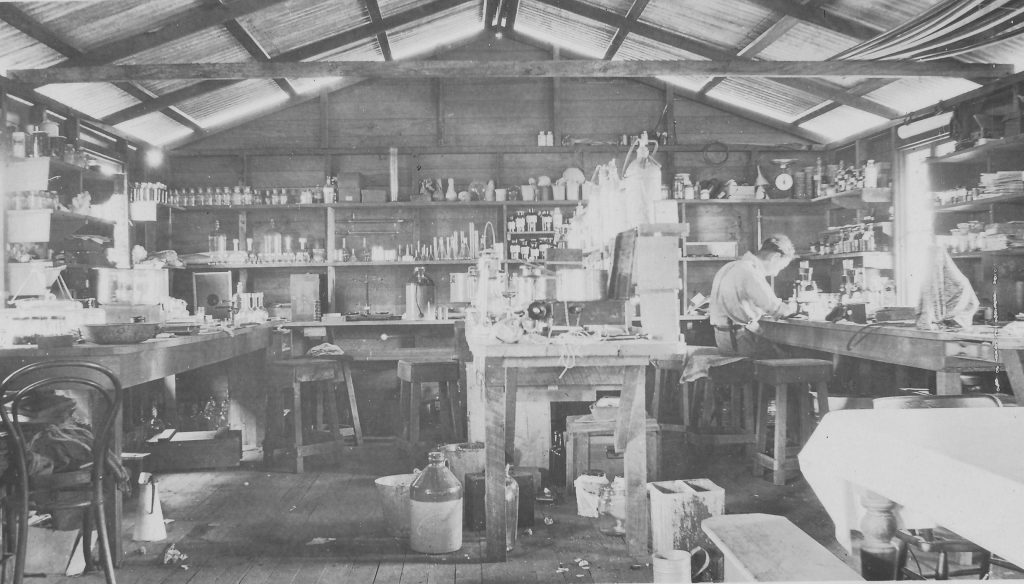

Most of the team’s scientific equipment had already been shipped from England and transferred to Low Isles before their arrival. A volunteer naturalist named James Edgar Young had supervised the design and construction of six huts on site at Low Island. These were intended to variously function as a laboratory, married and single living quarters, kitchen, toilets and bathroom. Mr Young also saw to it that the huts were fully equipped with furniture and stores. Dr Maurice Yonge, in his report to the Great Barrier Reef Committee (published in 1931), explained just how important J.E. Young’s contribution was, noting:

The expedition owes a great debt to Mr Young. Scientific work was begun almost immediately after arrival, instead of being delayed for many weeks pending the completion of constructional work.

Young later added a small darkroom on the east end of the married quarters. For reasons of practicality, only a “bare modicum of furniture”[4] had been built, but extra pieces of furniture and shelving were soon ingeniously adapted from packing crates and empty kerosene tins. In addition to the newly constructed buildings, there was already a lighthouse on the island, and huts for the lighthouse keepers and their families. The buildings constructed for the expedition were not of a particularly permanent nature (being only timber and corrugated iron) because it was expected that in the event of a cyclone, the lighthouse would serve as a refuge for the island’s inhabitants as it had survived many cyclones since its construction in the late 1870s.

Once final preparations were in place, all that remained was for the party to travel the final 72 km of their epic journey to the island that would become their home for the next thirteen months. Yonge wrote of his first impressions of the Great Barrier Reef:

About noon on July 16th we sailed from Cairns on the M.L. Daintree on the forty-five mile journey to our final destination. Nothing could have been more perfect than our introduction to these lagoon seas on which so much of our time for the coming year would be spent. The alluvial flat upon which Cairns stands soon disappeared from view. We passed over the calmest of blue waters beneath a clear sky and a vivid sun.[5]

The title for this chapter was inspired by one of the books from the Sir Charles Maurice Yonge Collection: A Naturalist’s Holiday by the Sea, by Arthur de Carle Sowerby, 1923.

- Mattie J. Yonge, "Log of outward journey to Great Barrier Reef, 28 May 1928-4 July 1928", unpublished journal (Sir Maurice Yonge papers, National Library of Australia, 1928), p. 13 https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1127491484/findingaid#nla-obj-1555316702 ↵

- Charles Maurice Yonge, A Year on the Great Barrier Reef, (London: Putnam, 1930), 24. ↵

- Charles Barrett, “Romance of the Great Barrier Reef ‘1,000 Miles of Mystery and Wonder.’ British Expedition’s Researches.” The Advocate, July 18, 1928, 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article67600900. ↵

- Yonge, A Year, 27. ↵

- Yonge, 25. ↵

A member of the Australian Great Barrier Reef Committee, James Edgar Young was a naturalist and experienced bushman, who had been a member of explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins' expedition to northern Australia in 1923 to collect flora and fauna for the British Museum.