1 Once Upon a Tide

Trisha Fielding

In July 1928, a group of British and Australian scientists embarked on an expedition to investigate a section of the largest coral reef in the world – the Great Barrier Reef – off the coast of Queensland. Jointly funded by Australian and British interests, the expedition spent a year at Low Isles, near Port Douglas, investigating the biological and geological complexities of a section of the reef. The expedition was primarily about discovering the conditions under which coral reefs existed and flourished; however it also had an economic objective: to investigate the commercial potential of the Great Barrier Reef’s resources.

At this time, there was still much to learn about the Great Barrier Reef. Theories as to the formation of coral reefs, such as those put forward by Charles Darwin and Alexander Aggasiz, remained contested.[1] The work of other scientists, including Joseph Beete Jukes, John MacGillivray, William Saville-Kent and Charles Hedley had shed some light on the mysteries of the Great Barrier Reef, but a comprehensive scientific investigation had not yet been attempted. The formation of the Great Barrier Reef Committee in Australia in 1922 marked the start of several years of agitation by Australian scientists and government officials who were eager to see Australia at the forefront of any future reef studies.

A professor of Geology at the University of Queensland – Henry Caselli Richards – believed that Australia should be doing more in the area of scientific research in the Pacific. He had attended the inaugural Pan-Pacific Scientific Conference in Hawaii in 1920, along with four other Australian representatives. It was here that Richards became keenly aware of just how far behind Australia was in the area of coral reef research.[2] Charles Hedley, of the Australian Museum, presented the only Australian paper at the conference in the section on Biological Research Stations. Hedley’s opening remarks were apologetic – Australia “did not have a single marine zoological station in Australia”.[3]

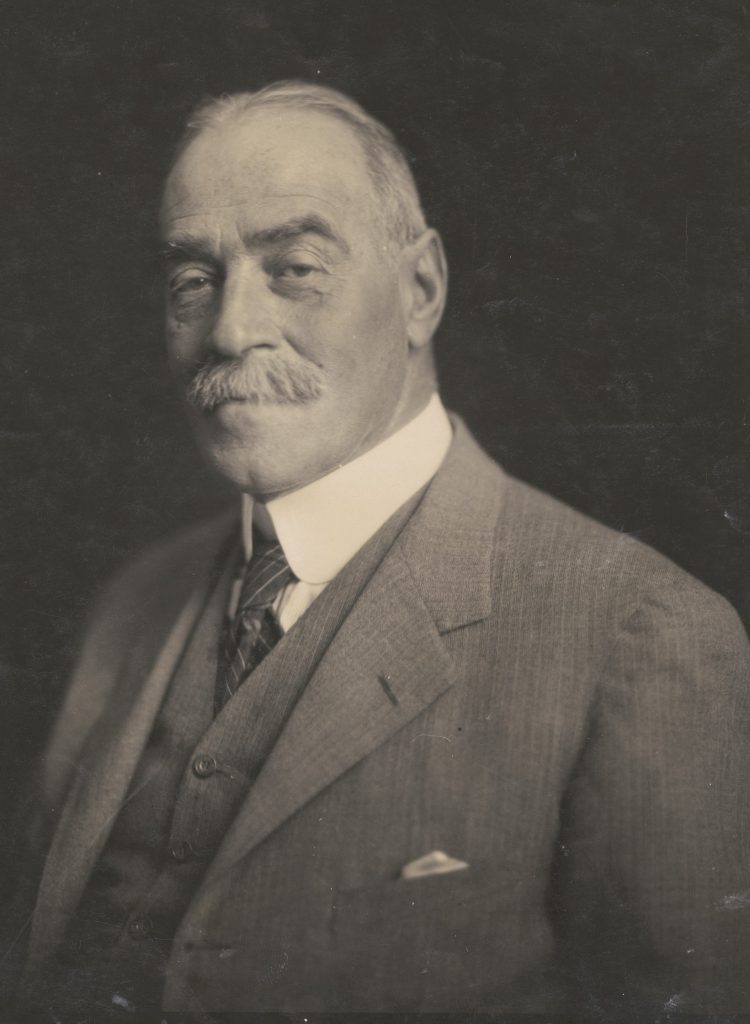

The following year, Richards sought the patronage of Queensland Governor, Sir Matthew Nathan, who was also President of the Queensland branch of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia. Nathan’s support would prove instrumental in the establishment of the Great Barrier Reef Committee. The two men worked well together, and in a complementary manner. Nathan could appeal to decision makers at the government level, while Richards had good connections in the scientific community in his capacity as Queensland Chair of what would later become the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

In 1922, after Richards had made the initial approaches, Governor Nathan invited Australian and New Zealand museums, universities and research societies, as well as several Australian government departments, to nominate representatives to form a committee.[4] Overseas, the Royal Geographical Society of London and the British Museum (Natural History) were also asked to become member organisations, and to appoint representatives that were either engaged in reef research or interested in promoting reef research.

The first meeting of the Great Barrier Reef Committee was held in Brisbane on 12 September 1922.[5] Sir Matthew Nathan was elected Chair, and Professor Richards Honorary Secretary. The Committee’s primary aim was to investigate the origin, growth and natural resources of the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. From its inception, the Committee was very active, holding 60 meetings in its first 11 years of operation, but for the first few years its resources were meagre. The ability to plan any serious research projects proved heavily dependent on the voluntary work of the Committee’s scientist members; and on the cooperation of government bodies, such as the Commonwealth Department of Navigation, the Queensland Marine Department, and the Royal Australian Navy (for survey data, and transport aboard survey vessels).

After Nathan’s term as Governor expired in September 1925, he retired to England, where he continued to promote both Queensland, and the Great Barrier Reef Committee (he was now Patron of the Committee, and Richards was Chair). Criticism of Richards’ bias towards geological reef research, to the detriment of biological studies of the reef, prompted a search for suitable young Australian graduates to participate in longer term projects, though it soon became clear that “very few, if any, young [Australian] marine zoologists [were] available to carry out the desired work on the reef”.[6]

In 1926, the Committee asked Sir Matthew Nathan to approach Cambridge University’s Professor John Stanley Gardiner to garner support for a “biological expedition” to the Great Barrier Reef. Acting as a representative of the University of Queensland, Nathan met with Gardiner at a conference in Cambridge in July. Gardiner was quick to offer his support and thought that the University of Cambridge might be willing to assist with funding for zoological graduates to participate in such an expedition.[7] The following year, an English Great Barrier Reef Committee was formed, with Nathan as its Chair, and Gardiner as joint Secretary.[8] According to scientist Barbara E. Brown, from this point onwards, Gardiner was “closely involved in every detail of the expedition’s organization”.[9] Though there was still much planning and negotiating to be done before the expedition would become a reality, Gardiner invested considerable energy into the project. According to Brown, Gardiner contributed to the development of the research program, and ensured funding for an expedition leader and for equipment and a library, from within his own department.[10]

The title for this chapter was inspired by one of the books from the Sir Charles Maurice Yonge Collection: Once Upon a Tide by Hervey Benham, 1955.

- For further general reading on these theories, see James Bowen, and Margarita Jean Bowen, The Great Barrier Reef: History, Science, Heritage (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2002); also Charles Maurice Yonge, A Year on the Great Barrier Reef, (London: Putnam, 1930). ↵

- Dorothy Hill, “The Great Barrier Reef Committee, 1922-1982: The First Thirty Years,” Historical Records of Australian Science 6, no. 1 (1984): 7, https://doi.org/10.1071/HR9840610001. ↵

- Bowen and Bowen, The Great Barrier Reef, 232. ↵

- Bowen and Bowen, 235-236. ↵

- Minutes No.1, September 15, 1922, Great Barrier Reef Committee Archive, University of Queensland Archives, cited in Hill, “The Great Barrier Reef Committee.” ↵

- Bowen and Bowen, 250-252. ↵

- Hill, “The Great Barrier Reef Committee,” 5. ↵

- Charles Maurice Yonge, “The Great Barrier Reef Expedition, 1928 – 1929,” Reports of the Great Barrier Reef Committee 3, (1931): 2, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/156399. ↵

- Barbara E. Brown, “The Legacy of Professor John Stanley Gardiner FRS to Reef Science,” Notes and Records 61, no. 2: 213, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2006.0176. ↵

- Brown, “The Legacy,” 213. ↵