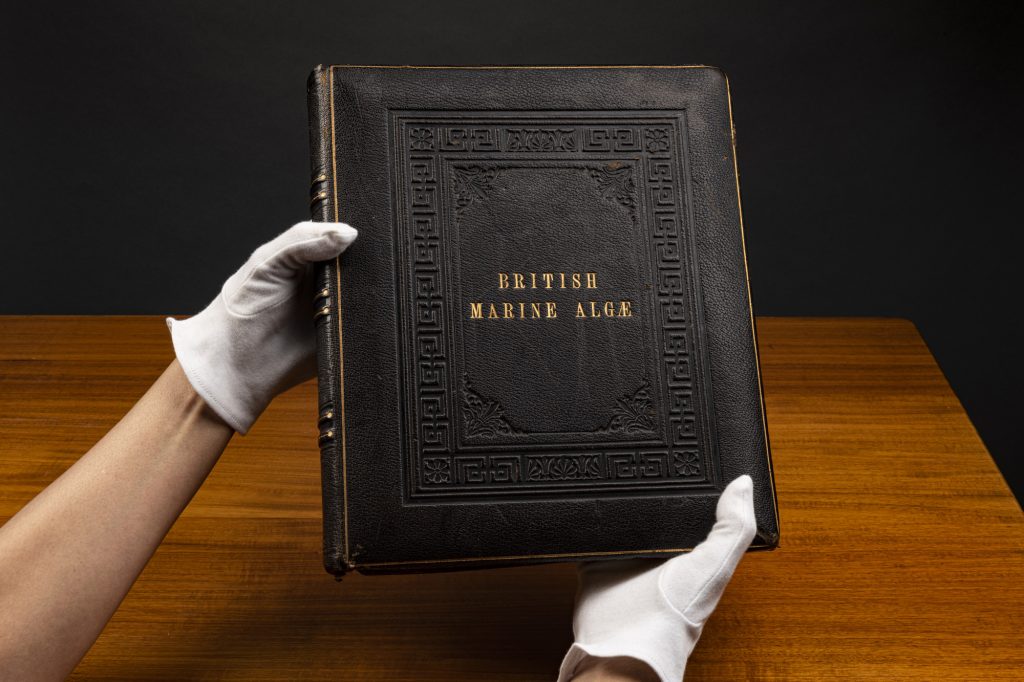

16 Slade’s British Marine Algae

Liz Downes

About the Compiler

About the Album

It is interesting to speculate where and when Sir Maurice Yonge acquired British Marine Algae, an album of pressed seaweeds collected from England’s Devonshire coast towards the end of the nineteenth century. A clue might be found in the fact that, as a young man, Yonge spent several years at the Marine Biological Association’s laboratory in Plymouth.[3]He was known to be a passionate bibliophile, who frequented antiquarian bookshops[4] and, since Plymouth is less than 60km from both the home of the album’s compiler, Annie Slade, and the sites where the seaweeds were collected, it is quite likely that Yonge discovered the album while he was in Devon early in his career.

Viewing this album today brings an element of surprise—the collection and preservation of marine algae seems an unlikely pastime for Victorian ladies. Middle- and upper-class women were generally expected to develop their skills in music, or the domestic and decorative arts. But the spread of industrialisation brought a growing appreciation of outdoor activities in the healthy air of countryside or seaside. In turn, this gave women opportunities for less conventional pursuits; ‘sea-weeding’ became quite a fashionable pastime, with the added spice of adventure as the women contended with waves, tides or slippery rocks.[5]

But for some women there was a more serious purpose. In Britain the nineteenth century saw a flourishing of interest in the natural sciences, yet women were largely excluded from the scientific societies that sprang up around the country. Seaweed collection and examination provided an avenue for women to participate actively in scientific discovery and, in some cases, brought recognition from men working in the same field.[6] Slade’s album speaks to a relationship between women and science which had been quietly, if tentatively, developing throughout the century. To set the album in context it is instructive to consider the work of some of these collectors.

Several decades before Slade was roaming the shores of Torbay, Amelia Griffiths (1768-1858), a parson’s widow with several children, had also collected algae in the same location. She often assisted male colleagues with species identification, becoming a valued friend and collaborator of leading British botanist William Henry Harvey.[7] In her lifetime Griffiths collected and preserved 250 different seaweed species and was among the first women to have her work recognised by the scientific community. Her seaweed albums are held in several museums, including at London’s Kew Gardens. The Griffithsia genus of red algae was named in recognition of her work.[8]

One of Griffiths’ former servants, Mary Wyatt (1789-1871), often accompanied her mistress on collecting trips, eventually setting up a shop selling marine specimens including seashells, fossilised corals and pressed algae. The two women collaborated in producing books on seaweed identification, which were sold in Wyatt’s shop, helping to spread the popularity of ‘seaweeding’ at coastal holiday resorts.[9]

On the Sussex coast, children’s author Margaret Gatty (1809-1873) took up seaweed collecting during a period of convalescence. It was to become a lifetime passion. Her two- volume British Sea Weeds took 14 years to complete, described 200 species and contained 86 coloured plates.[10] The Australian alga Gattya pinnella is one of several species bearing her name.[11] In mid-century, Anna Atkins (1799-1871) used the new medium of photography to create striking cyanotype photogenic images of seaweeds. Between 1843-53 she published the three-volume Photographs of British Algae which pioneered photography as a means of botanical illustration.[12]

Annie Slade was thus quite a latecomer on the scene. On completing her album she inserted a bookplate with the date February 21, 1884 – she would have been 23 years old – along with her name and the names of Mr & Mrs Edmund Slatter, who were to be the lucky recipients of this unusual gift.

Given that Paignton also lies on the shores of Torbay, it is possible that Slade knew of the pioneering work of Amelia Griffiths and Mary Wyatt many decades earlier. Might she have used their books for identification or modelled her album on those of Griffiths? Certainly the Slade album resembles the description of one of the leather-bound Griffiths volumes held in Exeter’s Royal Albert Memorial Museum, in which each sample is “mounted on stiff white paper and annotated with the name and location in … neat handwriting”.[13]

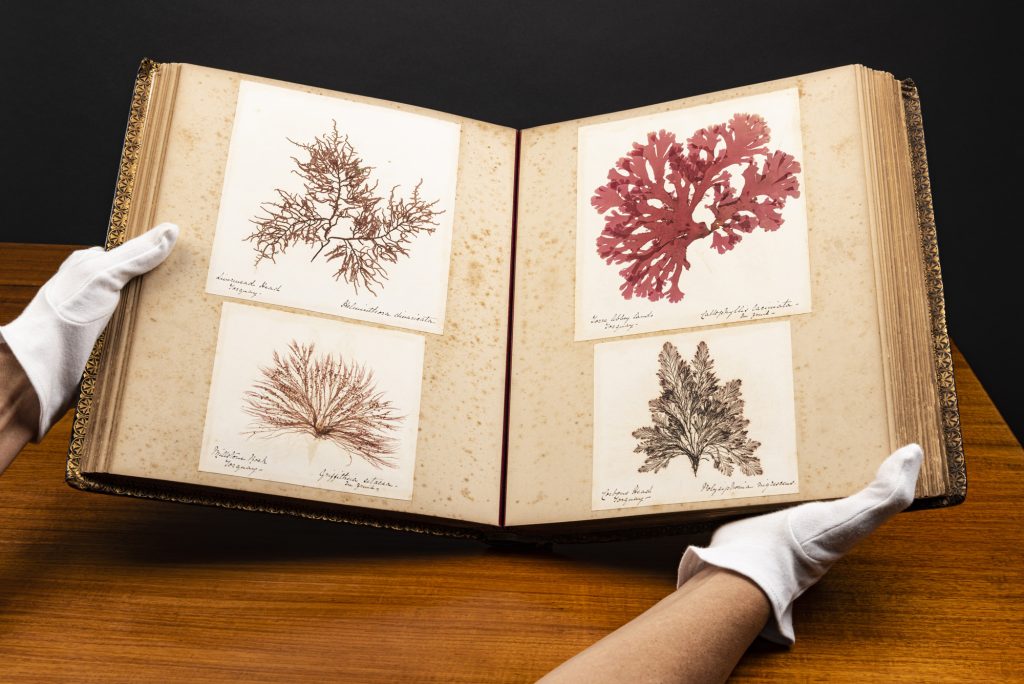

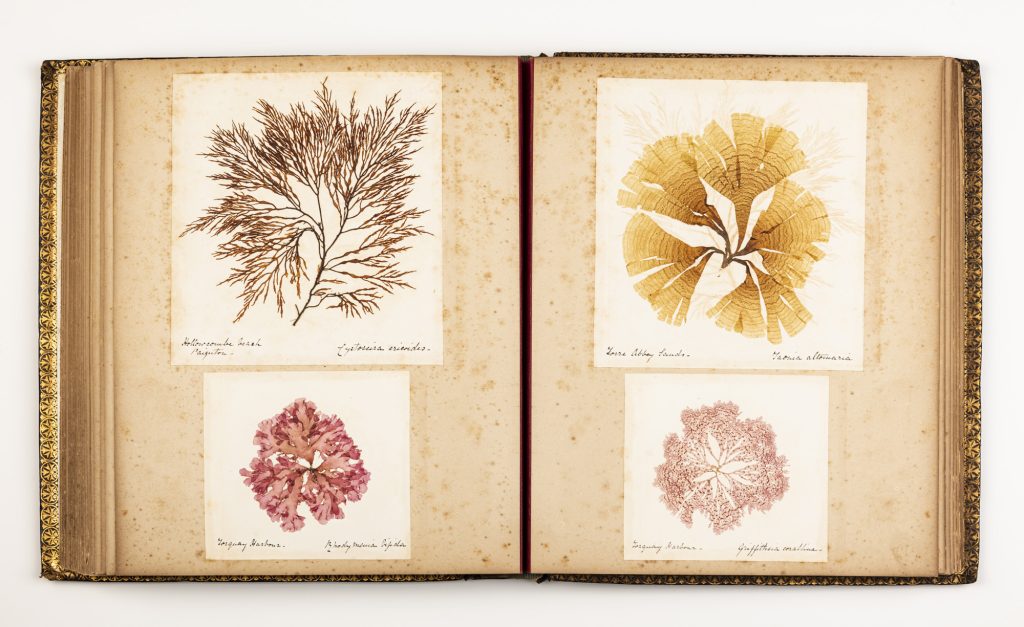

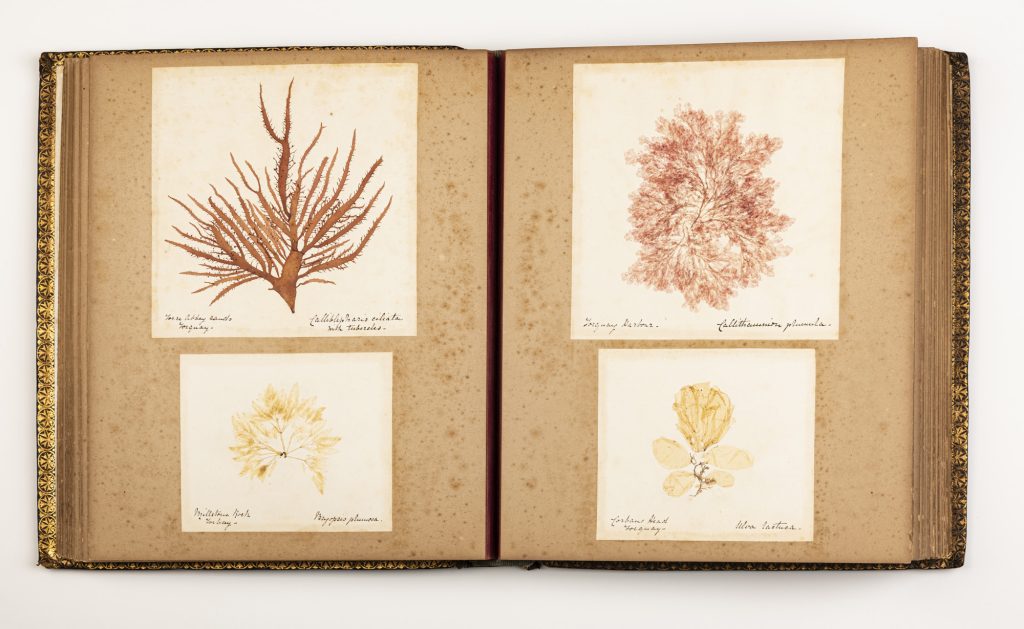

The Slade album contains 35 seaweed specimens each identified by its contemporary botanical name and place of collection. All three groups of macroalgae (red, green and brown alga) are represented and all but two specimens were from locations in Torbay. Slade’s consistency in providing exact details of each collection site, and the absence of this information for the two specimens simply labelled ‘Scotland’, suggest the latter were either purchased or received as a gift.

What is so remarkable about this, and similar albums from the Victorian era, is how well the specimens have retained their colour, shape and clarity of detail after so many decades. The process of preservation was painstaking but not difficult. It was outlined in detail by the American A.B. Hervey in his 1881 book, Sea Mosses: A Collector’s Guide.[14]The equipment required was simple: pliers, scissors, wash bowls, blotting paper, cotton cloth and mounting cards. A stick with a needle inserted in one end was used to gently separate the various parts of the plant to display its finer details. Seaweed-pressing had one key advantage over flower-pressing: no fixative was needed to secure the specimen to its mounting board as Hervey explained: “there is sufficient gelatinous matter in the body of the plant to make it perfectly adhere to the paper without other aid”.[15] The Slade album, where each specimen seems to have become one with the mounting paper, is proof of the enduring properties of this seaweed glue.

Within a few years of the album’s date, Slade had married and moved to the land-locked county of Surrey in south-east England where the couple raised four sons. It is unlikely that her new life and location would have allowed much, or any, opportunity for seaweed-collecting ventures to the coast and there is no evidence that she pursued her earlier interest. Nonetheless, no matter how or where Sir Maurice Yonge came across her album, it is easy to see why he was drawn to it. While some compilers liked to arrange their collections in decorative patterns, or even accompanied by snatches of poetry, Slade has presented her specimens with care, precision and an appealing simplicity; each species displays its intrinsic beauty and structure in the finest detail but without any further embellishment. No doubt Yonge also appreciated how, by correctly identifying each species and adding only its scientific name and the exact site of its collection, this young woman was following basic scientific practice.

British Marine Algae represents one woman’s venture into the field of marine botany when, notwithstanding the pioneering work of some remarkable women earlier in the century, female participation in scientific study was much more the exception than the rule. The Slade album celebrates both the beauty of nature to be found between the tides, and the human desire to investigate, record and understand natural phenomena, which is at the root of scientific endeavour.

- Richard Farrow, “Simla: The Coach House on the Hill,” Paignton History (blog), August 1, 2019, https://paigntonhistory.home.blog/2019/08/01/simla-the-coach-house-on-the-hill/. ↵

- Clive Orton, “Band of Brothers: The Ainger Brothers of Epsom,” The Past on Glass & other Stories (blog), March 2, 2017, https://pastonglass.wordpress.com/2017/03/02/band-of-brothers-the-ainger-brothers-of-epsom/. ↵

- Brian Morton, “Charles Maurice Yonge: 9 December 1899 - 17 March 1986,” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 38, no. 38 (November 1992): 383-386, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbm.1992.0020. ↵

- Morton, “Charles Maurice Yonge,” 409. ↵

- Cara Giaimo, “The Forgotten Victorian Craze for Seaweed Collecting,” Atlas Obscura, November 14, 2016, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-forgotten-victorian-craze-for-collecting-seaweed. ↵

- Giaimo, “The Forgotten Victorian Craze.” ↵

- William Henry Harvey, A Manual of the Marine British Algae: Containing Generic and Specific Descriptions of all the Known British Species of Sea-weeds (London: John Van Voorst, 1841), https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.137927. ↵

- Philip Strange, “The Queen of Seaweeds: The Story of Amelia Griffiths, an Early 19th Century Pioneer of Marine Botany,” Philip Strange Science and Nature Writing (blog), August 19, 2014, https://philipstrange.wordpress.com/2014/08/19/the-queen-of-seaweeds-the-story-of-amelia-griffiths-an-early-19th-century-pioneer-of-marine-botany/. ↵

- Strange, “The Queen of Seaweeds.” ↵

- Mrs Alfred Gatty and William H. Harvey, British Sea Weeds: Drawn from Professor Harvey’s “Phycologia Britannica” (London: Bell and Daldy, 1863), https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/british-sea-weeds-drawn-professor-harveys-phycologia-britannica-gatty-alfred. ↵

- Giaimo, “The Forgotten Victorian Craze.” ↵

- Hunter Oatman-Stanford, “When Housewives Were Seduced by Seaweed,” Collectors Weekly, November 7, 2013, https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/when-housewives-were-seduced-by-seaweed/. ↵

- Strange, “The Queen of Seaweeds.” ↵

- Alpheus Baker Hervey, Sea Mosses: A Collector’s Guide and an Introduction to the Study of Marine Algae (Boston: S.E. Cassino, 1881), 19 – 28, https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.64258. ↵

- Hervey, Sea Mosses, 26. ↵