14 Barbut’s The Genera Vermium

Suzie Davies

About the Author

James (sometimes Jacques) Barbut, (1711?-1791?) was a British naturalist and painter, specialising in still life paintings/images.[1] He exhibited many paintings at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from 1777-1786, with shells and marine themes reoccurring in his works. Despite his fine work and obvious recognition in his field, there seems to be very little substantial biographical material available about Barbut. His death is reported in The Literary and Biographical Magazine, and British Review, for January 1791. His birth date, however, is unverified.[2]

Barbut published The Genera Vermium… Intestina et Mollusca in London in 1783. He then went on to publish a second part in 1788, describing more examples from the Genera Vermium: Testacea, Lithophyta, and Zoophyta Animalia. Copies of both works are held in the Sir Maurice Yonge Collection (RB0040 (1783), RB0127 (1788)). Barbut’s other published works are: The genera Insectorum of Linnæus exemplified in various specimens of English insects drawn from nature. Les genres des Insectes de Linné; constatés par divers échantillons d’insectes d’Angleterre, copiés d’après nature. London: Dixwell, 1781, and The genera Vermium of Linnæus part 2d. Exemplified by several of the rarest and most elegant subjects in the orders of the Testacea, Lithophyta, and Zoophyta Animalia, accurately drawn from nature. With explanations in English and French. London: White, 1788.

About the Book

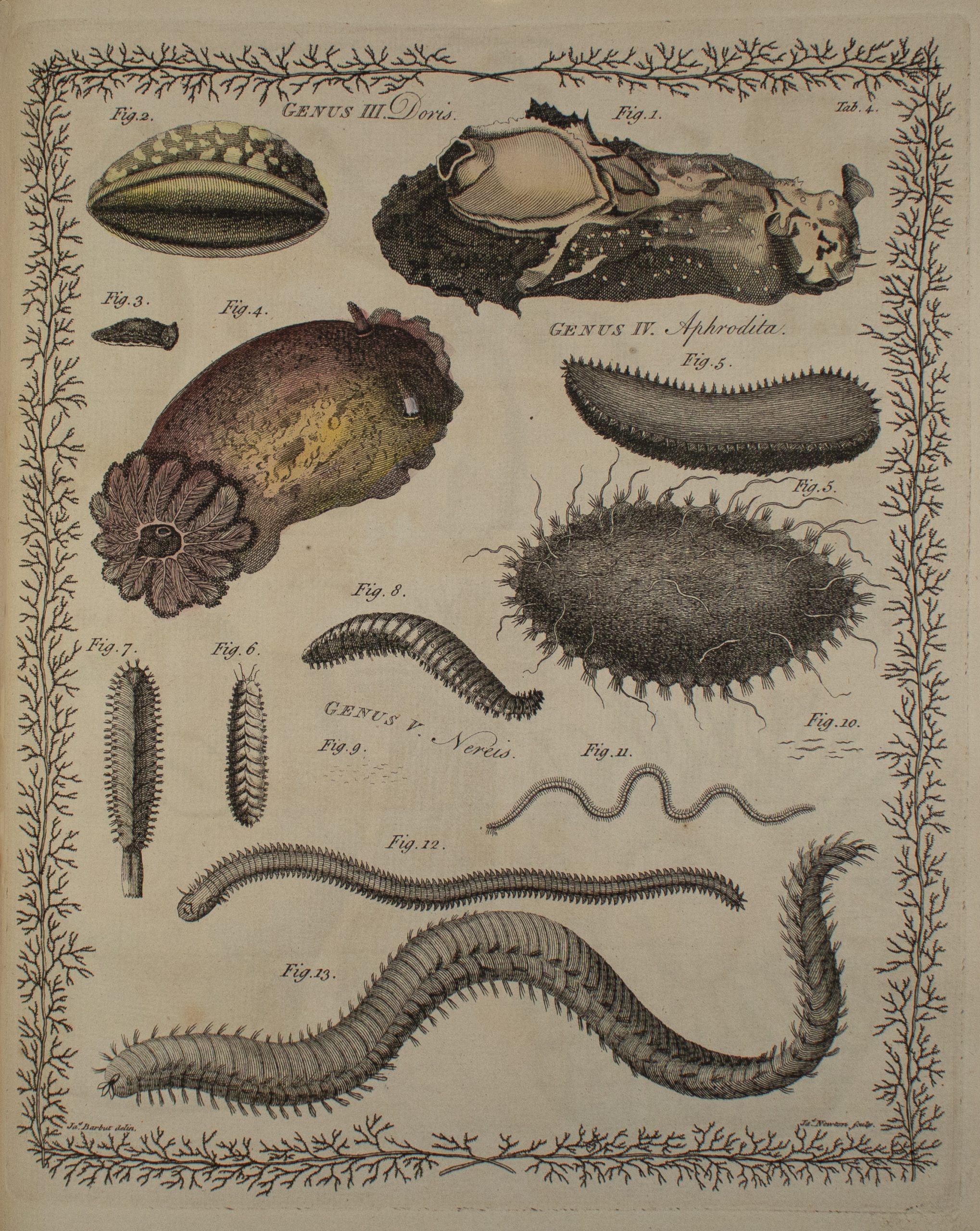

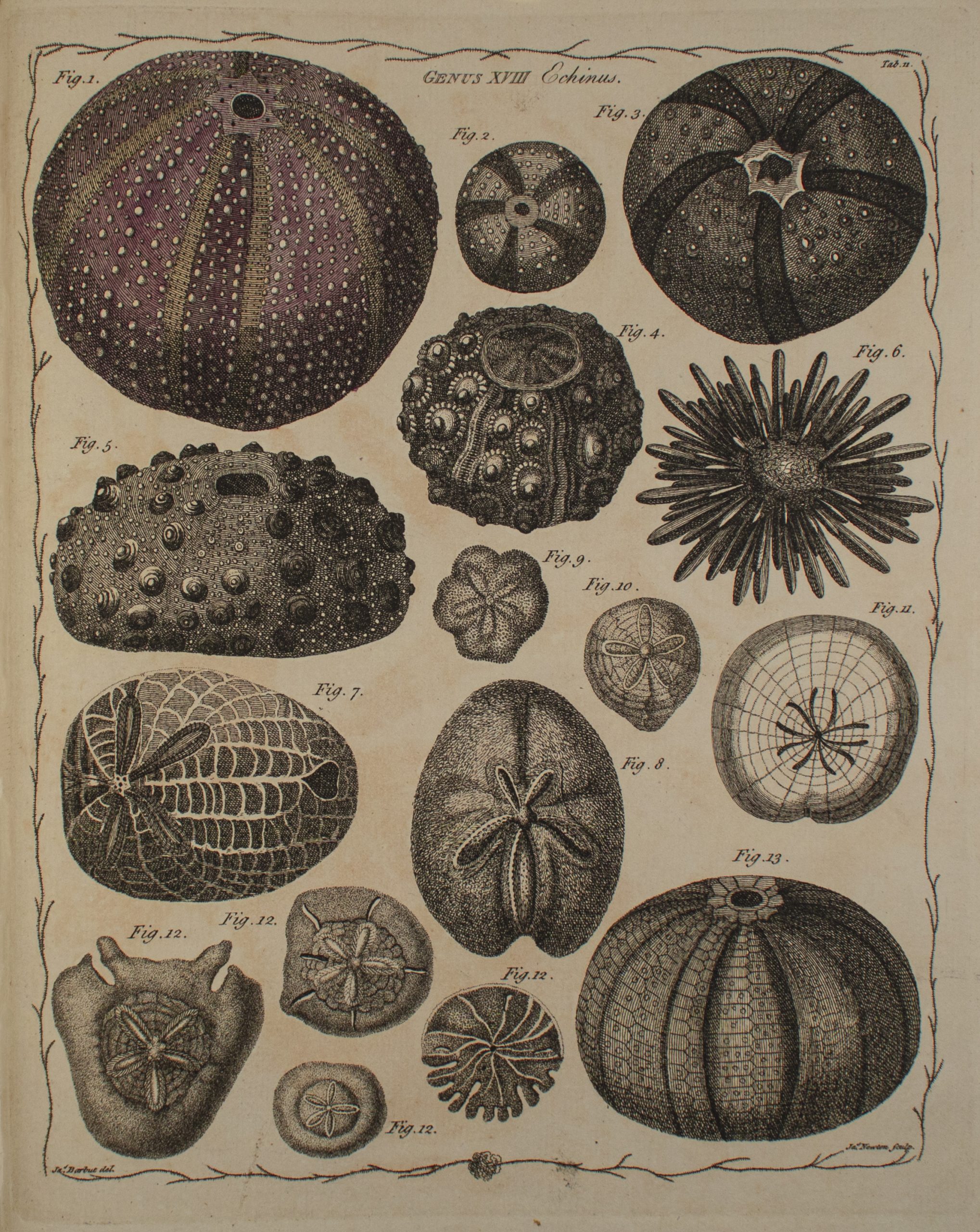

James Barbut published this work in London in 1783 (RB0040), with a second part (sometimes described as a second edition) released in 1788 (RB0127). This smallish attractive 1783 book holds 11 coloured plates of great detail showing representatives of animals from Linnaeus’s Intestina and Mollusca. The title page is shown in English and French, and the full book text follows in English and French throughout.

Barbut was not a wealthy man. He financed his book through a long list of subscribers, including Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society.[3] Barbut showed a pioneering spirit and optimism for his studies, with powerful quotes throughout his works, such as:

In the museum of that excellent naturalist the late learned Doctor Solander, was an animal of most beautiful pale violet blue color, taken in the South Sea… (Last page of “Animal Descriptions”, page 94)

So prolific is nature in all her works, sporting with her amazing powers, over all the creation, and proving the vast source of wisdom, from whence her operations flow. (At end of “Preface”, page xv)

Pliny the Elder is quoted on the Title page:

While I contemplated nature, She wrought in me a persuasion, that I should look upon Nothing as incredible that related to her. Plin. II 3.

Running through this work is Barbut’s enthusiasm for Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the Swedish botanist who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms, which is still used today.[4] At times, Barbut’s enthusiasm for his subject matter went from merely embracing the Linnaean system to fanaticism:

When we consider the station of animals which inhabit the deep, we need not wonder that this part of nature has not been thoroughly illustrated…. The immortal Linnaeus with infinite judgement, has exhibited an arrangement of the testaceous animals… which is certainly the most scientific method… and though certain persons have taken the liberty to criticize the works of this wonderful man, they are much inferior to him in brilliancy of wit and fidelity of judgement, as a glow worm is to the evening star. (page iii)

This work contains illustrations by Barbut, who was a well-regarded artist. It also includes work by several other notable illustrators and engravers, as does the second edition. Two of those represented in this work, Henry Mutlow and Thomas Woodman, worked in partnership, being major engravers of banknotes and maps.[5] Mutlow was also Engraver to the King. Engraver, James Newton, was well known for his portraits, genre scenes and landscapes. Newton produced several portraits of important members of the Royal Society in the late 1770s. His most famous was a portrait of Sydney Parkinson, the brilliant young Scottish botanical illustrator and natural history artist who accompanied Sir Joseph Banks and James Cook on the voyage of the HMS Endeavour.[6] Newton’s portrait is only one of two known portraits of Parkinson to exist.[7]

All of the book’s 11 plates (apart from the added title plate) are hand-coloured, with the engravers’ names being shown at the bottom of each illustration. Plate 10 is signed as drawn and engraved by Jas. Barbut. All others are signed as drawn by Jas. Barbut and engraved (or sculpted) by James Newton, apart from the added engraved title plate, signed as engraved by T. Woodman and H. Mutlow, and Plate 6, signed as engraved by J. Taylor.

This particular volume has leather binding, with the front and back covers embossed with a gold coat of arms called ‘The Society of Writers to the Signet (WS)’. The WS Society is a private society of Scottish solicitors, dating back to 1594, when it was formally established by the King’s Secretary.[8] Historically the Society had considerable power and major privileges and freedoms not afforded to other professional groups. Today, the Society maintains the Signet Library, part of the Parliament House complex in Edinburgh. The library building is a classical masterpiece with a Category A Heritage Listing. It still functions as a working centre for legal research.

A second part of Barbut’s work appeared in 1788 entitled The genera Vermium of Linnaeus part 2d: Exemplified by several of the rarest and most elegant subjects in the orders of the Testacea, Lithophyta, and Zoophyta Animalia. The second edition includes an Apology, in which Barbut states that, unable to procure some animals, he has turned to literary sources, and acknowledges the assistance of T. Pennant, Dr Bohadsch, Seba and Mr J. Clancy, Master in the Royal Navy. The second edition holds 14 plates, all different to the previous work, with all plates being hand coloured quite beautifully.

A concluding quote from Barbut’s shows his dedication to his work and his belief in a higher purpose behind scientific description of the natural world:

Let us take a nearer view of them, and our admiration will increase as our ignorance wears away; and the mind shall become illumined, and in the holy exultation of our hearts, we shall cry aloud, O God, how wondrous are thy works! (page v-vi)

- David M. Damkaer, The Copepodologist’s Cabinet: A Biographical and Bibliographical History (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002), 96-98. ↵

- Jerry Stannard, “Pliny the Elder: Roman Scholar,” In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., accessed June 19, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pliny-the-Elder. ↵

- Stannard, “Pliny the Elder.” ↵

- Damkaer, The Copepodologist’s Cabinet, 96-98. ↵

- “Henry Mutlow,” The British Museum, accessed October 17, 2022, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG159615. ↵

- William P. Howey, “Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771),” Scone Vet Dynasty, October 17, 2022, https://sconevetdynasty.com.au/sydney-parkinson-1745-1771/.; “Portrait of Sydney Parkinson,” The Royal Society Picture Library, accessed October 19, 2022, https://pictures.royalsociety.org/image-rs-9203. ↵

- Rex Rienits, “Parkinson, Sydney (1745–1771),” In Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, published 1967, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/parkinson-sydney-2537/text3445.; “A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas,” Wikipedia, accessed October 19, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=A_Journal_of_a_Voyage_to_the_South_Seas&oldid=1108907747. ↵

- “Society of Writers to Her Majesty's Signet,” Wikipedia, accessed June 13, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Society_of_Writers_to_Her_Majesty's_Signet&oldid=894410377.; “Home Page,” WS Society, accessed May 8, 2019, http://www.wssociety.co.uk. ↵