5 Dwellers of the Sea and Shore

Trisha Fielding

Although the Great Barrier Reef Expedition was led by British scientists, it was a genuinely collaborative project, and Australia contributed its own expertise to the expedition. As well as the Queensland Government’s Frank Moorhouse, who was on Low Isles for the full year, the Australian Museum sent five scientific staff for short periods during the year. These were Tom Iredale, a conchologist, Gilbert Whitley, an ichthyologist, scientific cadets William Boardman and Arthur Livingstone, and Frank McNeill, a zoologist’s clerk. Aubrey Nicholls, a zoology honours student from the University of Western Australia, worked in a volunteer capacity for twelve months as C.M. Yonge’s assistant. A highly-regarded naturalist, H.S. Mort, of Sydney, spent six weeks on Low Island, encamped with the Museum personnel.

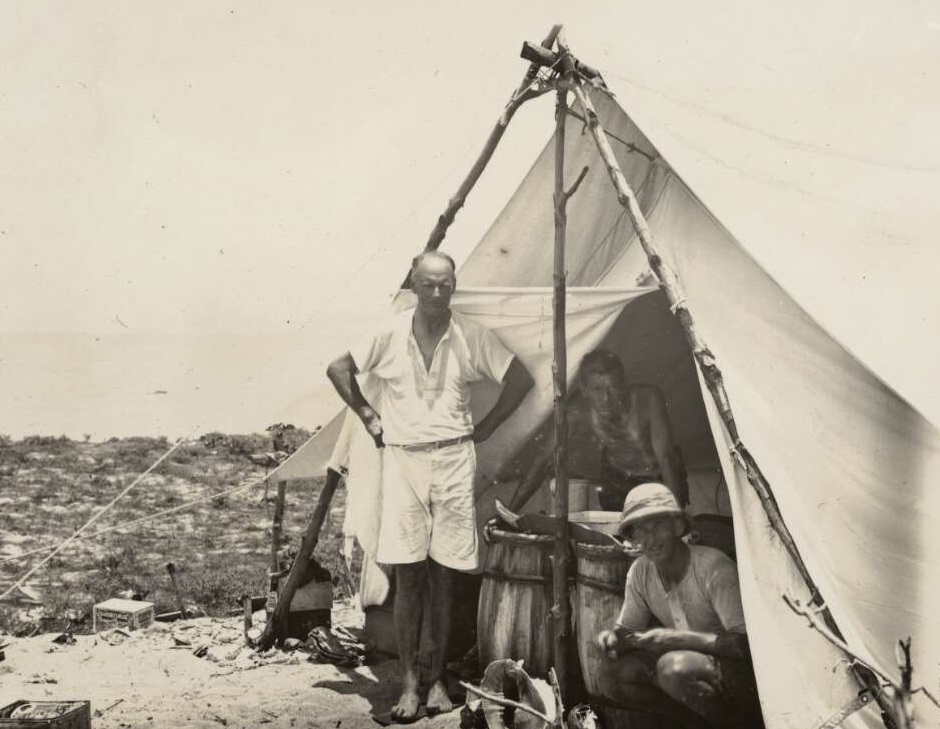

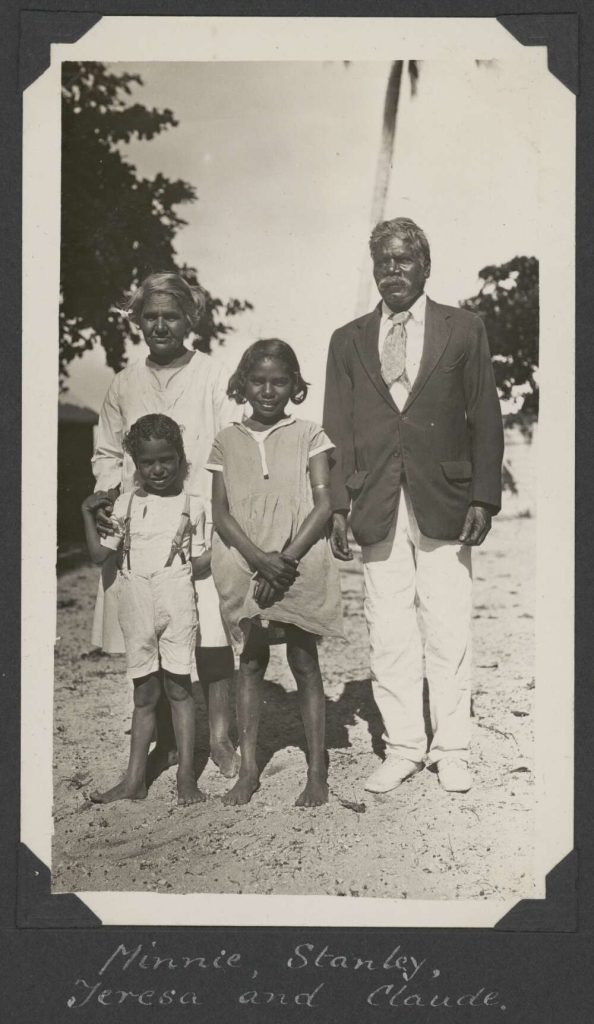

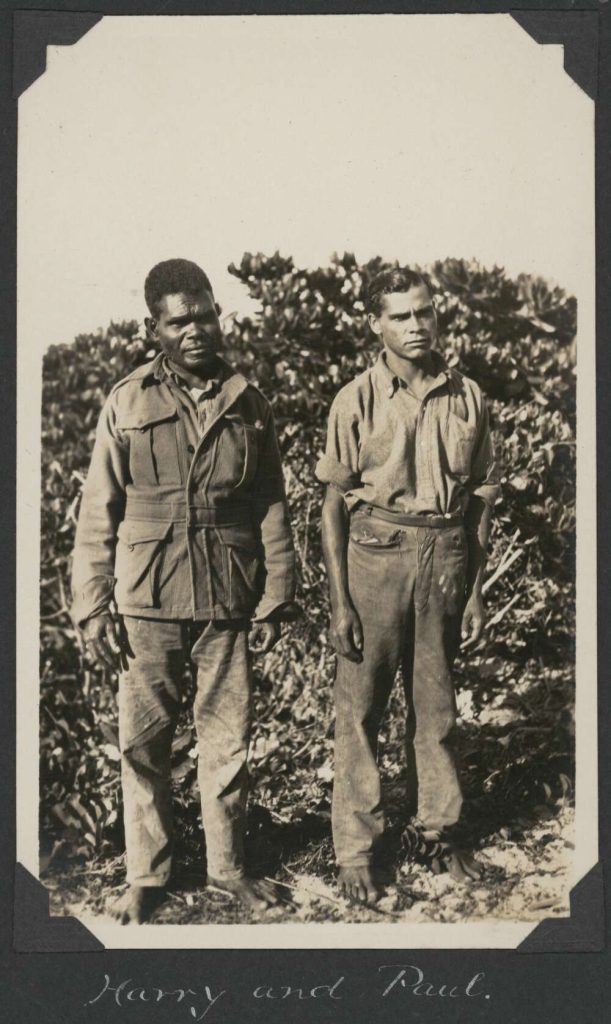

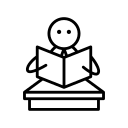

There were other support personnel too, without whom the entire expedition might have failed. As already noted, naturalist J.E. Young’s work on setting up and equipping the research station was invaluable. The lighthouse-keepers, Mr Carter, Mr Wilce, Mr Watkins, and Mr O’Meara, assisted with work of a practical nature, and allowed expedition members to use the lighthouse boats. Aboriginal workers were hired from the Anglican mission at Yarrabah to work at Low Isles. Andy and Grace Dabah were employed as handyman and cook respectively. Later, Claude and Minnie Connolly performed these roles. The Connollys’ two children, Teresa and Stanley, accompanied them on Low Isles for the duration of their stay. Yonge wrote that “Minnie was a good cook… [and] was a good worker, and took on practically the entire expedition’s washing – a formidable undertaking.”[1] Harry Mossman and Paul Sexton, also from Yarrabah, were hired for the full year to crew the research vessel Luana. Both men were married but their wives remained on the mainland while they worked at Low Isles (though they were able to make several short visits to see them during the year).

The Luana was a 39-foot ketch-rigged yacht with a 26hp auxiliary engine owned and skippered by A.C. Wishart who, together with another volunteer, H.C. Vidgen, sailed the vessel from Brisbane to Low Isles. As well as providing a vital communication and supply link to the mainland, the Luana enabled the “boat party” to carry out their scientific investigations both on and in the water. At times, larger boats with more powerful engines were hired to conduct short scientific excursions. These included the motor launches Merinda, Magneta, and Tivoli, all of Townsville; the Daintree, of the Daintree River Settlement; and the Athlone of Gladstone.[2] Although the Luana had not been built for marine biological work, Yonge felt that it had played a great part in the scientific success of the expedition and therefore its name should go down in history, having helped to advance the science of oceanography. In particular, Dr Yonge was genuinely appreciative of Wishart’s efforts, writing:

The greatest of good fortune came our way in the person of Mr A.C. Wishart of Brisbane, who offered the use of his boat, the Luana, and his services as skipper for the period of the expedition. We had very limited financial means to serve all our purposes, and the generosity of Mr Wishart and the great work which the Luana carried out are one of the principal reasons why this money proved a little more than sufficient for the fulfillment of the work of the expedition.[3]

Visitors to Low Isles

During the course of the expedition, Low Isles was visited by a steady parade of short-term visitors. Among the more notable guests were Professor Henry Caselli Richards, Chair of the Great Barrier Reef Committee; Miss Freda Bage, Principal of the Women’s College at the University of Queensland and a foundation member of the Committee; and Mr Heber Longman, Director of the Queensland Museum. Members of the general public too, were eager to see what was going on at Low Isles. The series of newspaper articles written by journalist Charles Barrett (who was the expedition’s first visitor), sparked such fevered interest in the expedition that people began making regular picnic excursions to Low Isles.[4] This “invasion” of curious onlookers proved to be a bit of a nuisance for the scientists, who had to erect makeshift fences around their experiments on the reef flat so that they would not be interfered with.

The title for this chapter was inspired by one of the books from the Sir Charles Maurice Yonge Collection: Dwellers of the Sea and Shore by William Crowder.

- Charles Maurice Yonge, A Year on the Great Barrier Reef, (London: Putnam, 1930), 29. ↵

- Charles Maurice Yonge, “The Great Barrier Reef Expedition, 1928 – 1929,” Reports of the Great Barrier Reef Committee 3, (1931): 14-15. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/156399. ↵

- Yonge, A Year, 114. ↵

- Charles Barrett, “Reef and Lagoon: Lovely Fish – and Snakes. Whale Joins the Party.” The Register, August 24, 1928, 13, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57058034. ↵

A person who collects and studies mollusc shells

A person who studies fish