7 Lady with a Spear

Trisha Fielding

One of the notable elements of the expedition, was both the presence and visibility of the female expeditioners. Initially, the British press attempted to trivialise the role of the women who were embarking for Australia, particularly Yonge’s “charming young wife”, Mattie, who was reported to be mostly concerned with what clothing she would take to Low Isles.[1] However, as well as being the expedition’s medical officer, Dr Mattie Yonge assisted with field observations, including monitoring temperature and wind speeds and direction at the research station using a sunshine recorder and an anemometer.

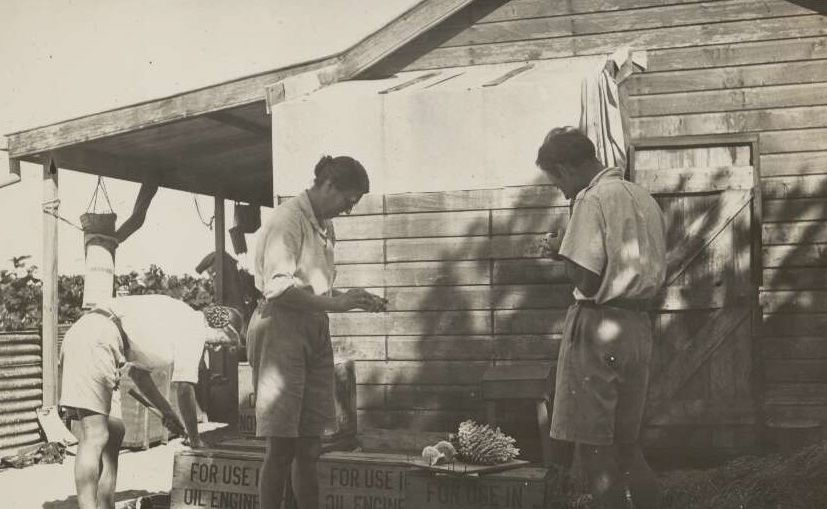

The Australian press, for its part, viewed the involvement of so many women in such an undertaking as something of a novelty, although one journalist, Charles Barrett, wrote more honestly about the women of the expedition. Far from playing a purely decorative, or even domestic role, the women in the team were highly accomplished in their respective fields, and did not shy away from any of the hard work, either scientific or practical. Zoologist Sheina Marshall was apparently an excellent woodworker and took to building wooden stools with a plane and hammer to supplement the meagre furniture at the research station. Barrett wrote that even out on the reef, the women “played their part” and were “keen on doing thoroughly the tasks allotted to them.”[2] Perhaps in an effort to circumvent any frivolous comments about them, one of the women told Barrett: “We are not ornamental… We have come here to work.”[3]

Zoologist Sidnie Manton joined the expedition at the end of March 1929, after having spent six weeks in Tasmania researching the freshwater crustacean Anaspides. Manton’s expedition diaries and letters home to her family provide a vivid picture of daily life at Low Isles. In her first letter penned on Low Island, she wrote:

The colours of things are marvellous, brilliant corals, clams of huge size – up to two feet, they are big bi-valves sitting with wide open mouths the inside all frills of the richest and most brilliant tints imaginable and every one differently coloured and patterned. One has to be careful not to put a foot inside a clam: small coral fish equally brilliant abound and likewise crabs. Sea urchins are lovely – spines of multi colours up to 10″ long and so on.[4]

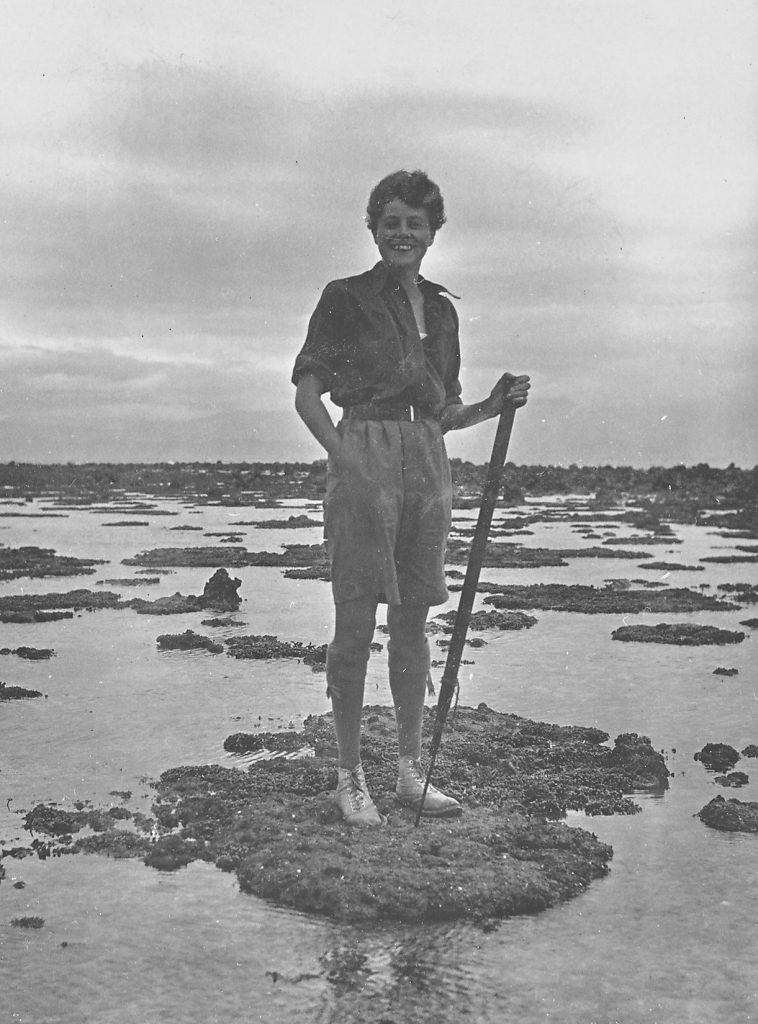

Manton’s genuine enthusiasm for her work is evident when she tells her family that she will be assisting the “reef party” with their work, explaining:

At spring tides I shall be out on the reef identifying and counting and mapping the distribution of reef animals in various places of different kinds – also collecting and pickling crustacea for them. During neaps I shall play about with feeding mechanisms and food of reef crustacea, and on starting some work in watching budding in corals.[5]

A few weeks later, after having done “a prodigious amount of pumping” for the more experienced divers, Manton was learning to use the team’s primitive diving equipment herself. On her first dive, she spent 10 minutes in about 15 feet of water, and wrote that:

It was simply marvellous, the water… was clear, and the sun shone down, and swarms of large and small fish, striped and wonderful colours swam about one and in the coral. I find it very difficult to walk about, I can keep upright easily, but it is difficult to get a push off with a foot as you try to walk… Doubtless I shall learn in time.[6]

Those women of the expedition without formal scientific qualifications and roles genuinely collaborated with their husbands in scientific work. This was particularly true of Anne Stephenson, who is credited as co-author with her husband T.A. Stephenson on two articles resulting from the research at Low Isles (and on another 12 articles with him on subsequent research in South Africa and North America).[7] Charles Barrett noted that:

Mrs Stephenson is out on the reef assisting her husband for hours every day, and in the lab, is seen poring over coral reef charts or consulting learned tomes of some branch of marine zoology.[8]

It was not without precedent for women to accompany their husbands on scientific field expeditions. Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz accompanied her scientist husband, Louis Agassiz, on trips to Brazil in 1865-1866 and to South America in 1871-1872. Using material from her own journal entries, along with her husband’s scientific field notes, Elizabeth published a number of books and journal articles in the latter part of the nineteenth century, including the works: A First Lesson in Natural History (1859), Seaside Studies in Natural History (1865), and A Journey in Brazil (1867). In 1897, Caroline (Cara) David accompanied her geologist husband, T.W. Edgeworth David, on a reef boring expedition to Funafuti, Tuvalu, though Mrs David’s role was a purely domestic one.

Therefore, it follows that the 1928-1929 Great Barrier Reef Expedition was ahead of its time for its inclusion of so many women in the research party. And buoyed by the involvement of their British counterparts, some Australian women scientists seized the opportunity to visit Low Isles during the course of the expedition. Freda Bage, biologist and Principal of the Women’s College at the University of Queensland (and the only female member of the Great Barrier Reef Committee), and Miss H.F. Todd, assistant secretary of the Committee, spent a week on Low Island before accompanying some of the expeditioners on a short holiday to the Atherton Tableland in early 1929.[9]

In addition, Welsh botanist Mary Glynne visited Low Isles in April 1929. Miss Glynne, whose field of specialisation was fungi, was in Australia for a year on a research fellowship, investigating the diseases of wheat. While at Low Isles, Miss Glynne studied marine algae on the reef and collected specimens of fungi and lichens.[10]

The title for this chapter was inspired by one of the books from the Sir Charles Maurice Yonge Collection: Lady with a Spear by Eugenie Clark, 1951.

- London Correspondent, “Barrier Reef: British Expedition,” Observer, June 30, 1928, 17. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164884269. ↵

- Charles Barrett, “Great Barrier Reef: Seeking Coral Secrets: Diving Amongst Sharks,” Western Mail, August 16, 1928, 14. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article38377221. ↵

- Barrett, “Great Barrier Reef,” 14. ↵

- Manton, Sidnie, Letters and Diaries, p. 59. ↵

- Ibid. pp. 59-60. ↵

- Ibid., p. 67. ↵

- See for example: Thomas A. Stephenson, Anne Stephenson, Geoffrey Tandy and Michael Spender, “The Structure and Ecology of Low Isles and Other Reefs,” Scientific Reports: Great Barrier Reef Expedition 1928-29 3, (1931): 17-112, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/183511; Thomas A. Stephenson and Anne Stephenson, “Growth and Asexual Reproduction in Corals,” Scientific Reports: Great Barrier Reef Expedition 1928-29 3, (1931):167-217, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/183516. ↵

- Barrett, “Great Barrier Reef,” 14. ↵

- “Visiting Scientists: The Low Island Party: Run to the Highland,” Cairns Post, January 2, 1929, 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article40653032. ↵

- “Current Events: Women and Research,” The Age, June 18, 1929, 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article205021772. ↵

A device that records the amount of sunshine at a given location or region at any time. The results provide information about the weather and climate as well as the temperature of a geographical area.

A device that measures wind speed and direction. It is a common weather station instrument.