12 Rumphius’ Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet

Suzie Davies

About the Author

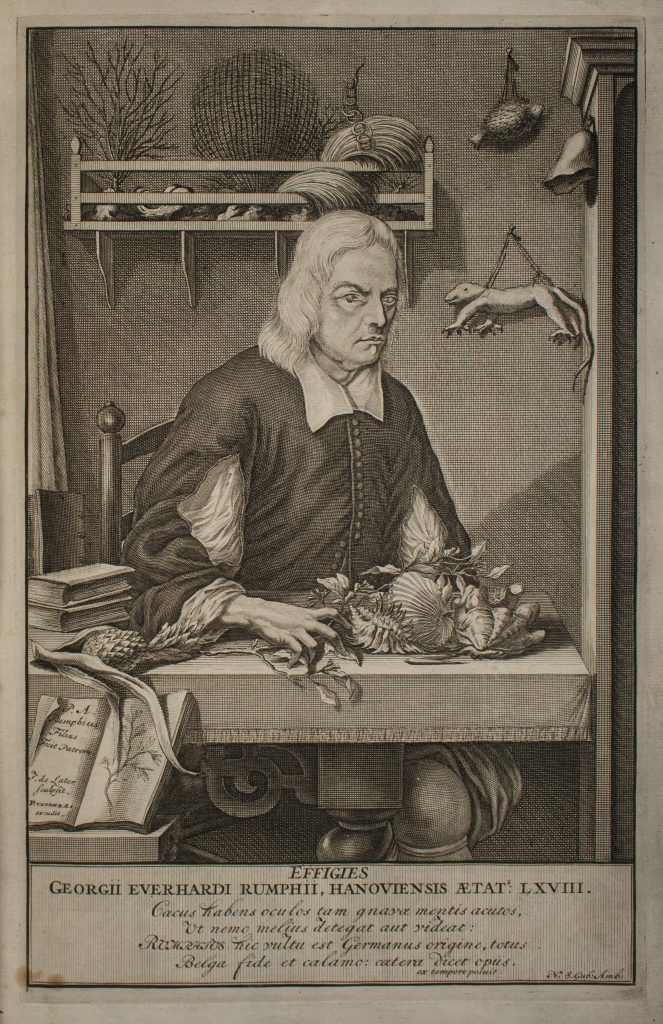

Georgius Everhardus Rumphius (originally Rumpf, 1627-1702), also known as the “Indian Pliny”, was one of the great tropical naturalists of the seventeenth century. Born in Germany, he spent most of his life in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, stationed on the island of Ambon in eastern Indonesia. Despite extensive personal tragedies, including the loss of his sight, Rumphius persevered to produce the definitive work of natural history on the region. Circumstances began to conspire against Rumphius in his efforts to understand the rich fauna and flora of his tropical paradise. Working in the glare of intense sun during the day and writing and drawing at night by candlelight, his eyesight began to fail. By 1670, Rumphius was blind, probably from glaucoma. His wife and children may have assisted Rumphius in taking his scientific notes and collecting specimens. On 17 February 1674 a powerful earthquake struck Ambon. A falling wall killed his wife and daughter.[1] Despite these personal losses Rumphius continued to compile his notes about the fauna and flora of this fascinating portion of Indonesia. By 1680, his manuscript was ready for publication. His record of the medicinal value of the local flora was unique. Fortunately the value of Rumphius’ work was recognised by a VOC official who obtained a copy of the manuscript before it was shipped to Europe for publication. When the ship transporting the original manuscript was sunk by a French vessel (France and the Netherlands were at war at the time), the existence of a copy meant that Rumpius’s work was not lost.[2]

Rumphius was elected as a member of what is now the oldest science society in the world, the Academia Naturae Curiosorum of the German Roman Empire (founded in 1657, today known as the Leopoldina). Members were given nicknames, his was “Plinius”, a most honorific title which referred to the Roman administrator Gaius Plinius Secundus (23-79 AD), one of the founders of European natural sciences.[3]

Rumphius undertook foundational work in Melanesian botany, zoology, geology (including the study of fossils), history, pharmaceutical, ethnological, linguistic, historical and religious matters, including astrology and magic. In addition to his major contributions to plant systematics, he is also remembered for his skills as an ethnographer and his frequent defence of Ambonese peoples against colonialism. To botanists, he is best known for his work Herbarium Amboinense, which was a seven volume folio work with extensive descriptions and discussions in Latin and Dutch of about 1200 species with over 800 full page illustrations. Decades after his death, the work was finally published in Amsterdam.[4][5]

About the Book

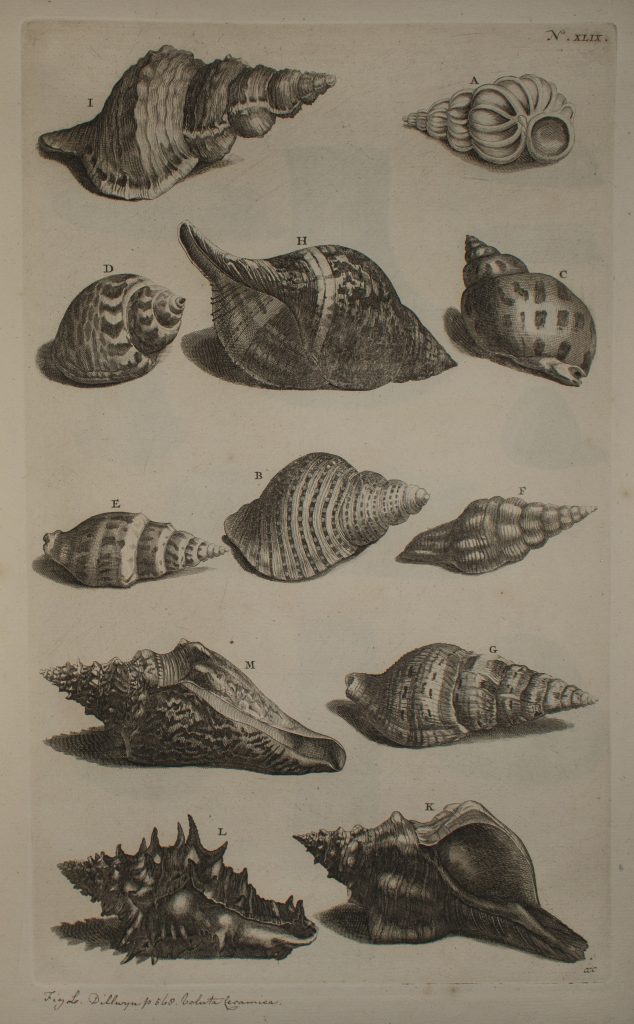

Thesaurus imaginum piscium testaceorum is the first edition in Latin of Rumphius’ Ambonese curiosity cabinet, a groundbreaking work on the natural history of the Molucca Islands and the Indonesian Archipelago with engraved plates after Maria Sibylla Merian. Rumphius’ Ambonese curiosity cabinet was first published in Dutch in 1705 (titled Amboinsche Rariteitkamer), the Latin edition followed in 1711. His greatest work, the seven volume Herbarium Amboinense was published between 1741 and 1755. Rumphius’ texts remain a significant record of the flora of Ambon.[6]

Rumphius may have lived and worked in a faraway isolated region of the world, but his impact on science continued to be enormous for centuries after his death. Centuries later, this pioneering influence was picked up by twentieth century malacologists such as Sir Maurice Yonge and S. Peter Dance. In his book Shell collecting: An illustrated history (which includes a fine foreword by C.M. Yonge), Dance describes Rumphius as a “remarkable man”:

The Amboinese Curiosity Cabinet, despite its unpromising title, is full of accurate and detailed observations on the invertebrate animals encountered by him and mollusks are given special attention… First and foremost he was a brilliant field naturalist… In the consistent and accurate recording of locality data, Rumphius was far ahead of his time and no less noteworthy is his attention to molluscan ecology, in which field he must be considered a pioneer.[7]

Rumphius’ original drawings were destroyed in a fire on Amboina in 1687, and by that point his blindness prohibited him from drawing new specimens himself. The plates in the posthumously published work were engraved after drawings by Maria Sybilla Merian, commissioned expressly for the work. Merian’s original drawings are in the Archives of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburgh.[8]

The copy of Thesaurus held at JCU Special Collections includes interesting notations on the verso pages of the front and back covers. The names of members of the Irish Cleland family (Richard Rose Cleland, and Ja. Clealand) are inscribed on the front pages, showing dates 1736, and 1806. Bookplates from James Cleland or Ja. Clealand, of Rathgill or Rath Gael House, near Bangor Island, are also present. James Cleland was a well-regarded naturalist in the 1790s, with a strong interest in conchology. While having no publications to his name, he was an avid shell collector, providing many species to James Sowerby for inclusion in the British Museum of Natural History.[9]

The Thesaurus holds some 60 magnificent copper engravings which can be separated into the following categories: crabs (12), sea-urchins & starfish (4), snails & muscles (33), and petrifications and minerals (11). The engravings are all large (20 x 32 cm) and exquisitely detailed. The very front page of the Thesaurus includes a full page portrait of Rumphius at age 68, by his son Paulus. Rumphius sits, clearly blind from glaucoma, but surrounded by his many plant and animal specimens. It is a very fine and remarkable illustration indeed, and creates an impressive introduction to an outstanding work of science.

- Georgius Everhardus Rumphius and E. M. Beekman, Rumphius’s Orchids: Orchid Texts from the Ambonese Herbal (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), xxxiv, ProQuest Ebook Central. ↵

- “Georg Eberhard Rumphius,” Wikipedia, accessed February 20, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Georg_Eberhard_Rumphius&oldid=826657993 ↵

- Veldkamp, “Georgius,” 1-15. ↵

- Veldkamp, “II. 15 June 2002,” 7-21. ↵

- Wikipedia, “Georg Eberhard Rumphius.” ↵

- Veldkamp, “Georgius,” 1-15. ↵

- S. Peter Dance, Shell Collecting: An Illustrated History (London: Faber & Faber, 1966), 48-49. ↵

- Veldkamp, “II. 15 June 2002,” 7-21. ↵

R. MacDonald and N. McMillian, “James Dowsett Rose Clealand (Cleland): A Forgotten Irish Naturalist,” The Irish Naturalists' Journal 13, no.3 (1959):70-72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25534641.pdf. ↵

R. MacDonald and N. McMillian, “James Dowsett Rose Clealand (Cleland): A Forgotten Irish Naturalist,” The Irish Naturalists' Journal 13, no.3 (1959):70-72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25534641.pdf. ↵