4 The Experimental Basis of Modern Biology

Trisha Fielding

Biological Section

The Great Barrier Reef Expedition was divided into two sections: a biological section and a geographical section. Within the biological section of the expedition, three separate research groups were formed. A boat party, a shore party, and a physiological (experimental) party. The initial boat party comprised Frederick Stratten Russell, of the Marine Biological Association at Plymouth, who had co-authored a book with the expedition’s leader, C.M. Yonge, entitled The Seas; Scottish chemist and hydrographer Andrew Orr; and Scottish zoologist Sheina Marshall. Russell’s wife Gweneth took part in a support role, mainly as his assistant. The boat party investigated zooplankton, phytoplankton, the chemistry and hydrography of the seawater, and the conditions over the reef flat and within the mangrove.

The shore party comprised Thomas Alan Stephenson, a zoologist and recognised authority on sea anemones from the University College in London; his wife Anne Stephenson, who lacked any science qualifications, but nevertheless assisted with the scientific work; botanist Geoffrey Tandy, of the British Museum; and Frank Moorhouse, a science graduate representing the Queensland Government. The shore party focused on the ecology of reefs and the breeding, development and growth of corals and other reef animals. Moorhouse, in particular, was specifically concerned with “economic products”, such as trochus, bêche-de-mer and sponges.

The physiological party, led by C.M. Yonge, looked at the feeding and digestion of corals and reef molluscs, the significance of zooxanthellae in the life of corals, the effect of sediment on corals, the calcium content of the sea, and how corals form their skeletons. This group also included Yonge’s wife Mattie as the expedition’s medical officer; Aubrey Nicholls, of Perth, Western Australia, who was designated as C.M. Yonge’s assistant; and G.W. Otter, an English zoologist.

Two later additions, Miss Sidnie Manton, of Cambridge University and Miss Elizabeth Fraser, of London, joined the expedition for four months and worked with the shore party. Both assisted with observations on the breeding of reef animals, and Manton also looked at the growth of corals. Yonge later wrote of Manton’s “exceptional intensity” when it came to her work, observing that as a result, “Sidnie did as much in those few months as the rest of us did in four times that period.”[1]

Geographical Section

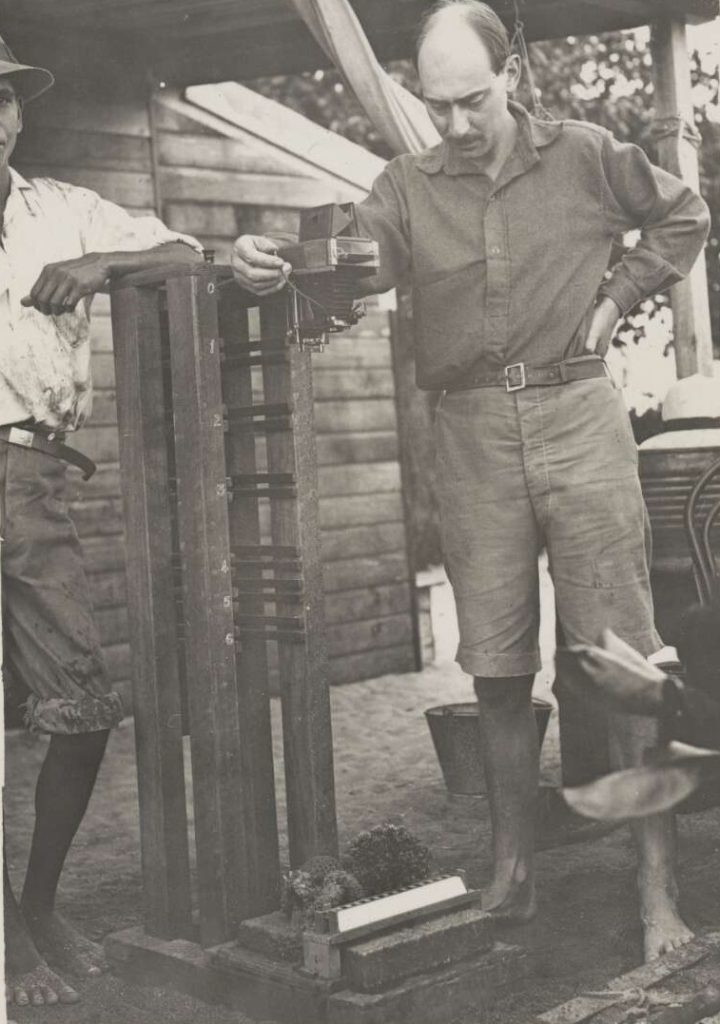

The geographical section of the expedition was independently funded by the Royal Geographical Society. It was led by Alfred Steers of Cambridge University, with Michael Spender, of Oxford University, acting as his assistant. They were later joined by E.C. Marchant, a recent Cambridge graduate, who stayed for six weeks. The section’s aim was to advance current knowledge on the origin of reef foundations and to establish the relationship of the coastline to submerged reefs, cays, and continental islands. The Townsville motor launch Tivoli was chartered to conduct a reconnaissance of the Queensland coast and adjacent reefs between Whitsunday Island and Flinders Island, at Cape Melville.[2] Many high islands, low wooded islands, sand cays, reefs, and parts of the mainland were visited during this excursion of almost 1,500km. Steers also made a journey from Brisbane to Mackay in the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service’s SS Cape Leeuwin. Bowen and Bowen describe the geographical component of the expedition as “close to a fiasco”.[3] They argue that Steers’ conclusions were based almost entirely on observations. The intention to map the coastline, continental islands and cays from stereo pairs of photographs obtained by photo-theodolite survey, proved impractical.[4] This equipment was too heavy to carry over steep terrain, and in any case, locations with thick vegetation proved a barrier to establishing clear sight lines.[5] However, Hopley et. al. argue that the work overseen by Steers was far from a fiasco and provided the “stimulus for much subsequent work”[6] and Spencer et. al. point out that

Steers was the first scientist to extensively study the reef islands of the Great Barrier Reef, separating out the often highly dissected high or rocky continental islands with their fringing reefs, distinguishing between sand cays and shingle cays and providing the descriptive term ‘low wooded island’ for the complex reef systems of the inner shelf north of 16° S.[7]

After Steers had returned to England at the end of 1928, and Marchant in January 1929, Spender stayed with the expedition until July 1929, making extensive surveys of Low Isles, and Three Isles, off Cooktown.

The title for this chapter was inspired by one of the books from the Sir Charles Maurice Yonge Collection: The Experimental Basis of Modern Biology by J.A. Ramsay, 1965.

- Geoffrey Fryer, “Sidnie Milana Manton: 4 May 1902 – 2 January 1979”, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 26 (November 1980): 329, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbm.1980.0010. ↵

- J.A. Steers, “The Queensland Coast and the Great Barrier Reefs,” The Geographical Journal 74, no.3 (September 1929): 232, https://doi.org/10.2307/1784362. ↵

- James Bowen, and Margarita Jean Bowen, The Great Barrier Reef: History, Science, Heritage (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 274. ↵

- Tom Spencer, Barbara E. Brown, Sarah M. Hamylton and Roger F. McLean, “A Close and Friendly Alliance: Biology, Geology and the Great Barrier Reef Expedition of 1928-1929,” in Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, eds. S. J. Hawkins and A. J. Lemasson, vol. 59, (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2021), 106. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003138846. ↵

- Spencer, “A Close and Friendly Alliance,” 106. ↵

David Hopley, Scott G. Smithers, and Kevin Parnell, The Geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef: Development, Diversity, and Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 10, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511535543. ↵

David Hopley, Scott G. Smithers, and Kevin Parnell, The Geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef: Development, Diversity, and Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 10, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511535543. ↵- Spencer, “A Close and Friendly Alliance,” 106-107. ↵

Plankton consisting of small animals and the immature stages of larger animals.

Plankton consisting of microscopic plants.

A genus of medium-sized to very large sea snails. The interior of their cone-shaped shell has a pearl-like finish and is used to make buttons.

A large sea cucumber, eaten as a delicacy in China and Japan. It is also known as trepang.

Photosynthetic algae that live within the cells of corals.