6 The Sun, the Sea and Tomorrow

Trisha Fielding

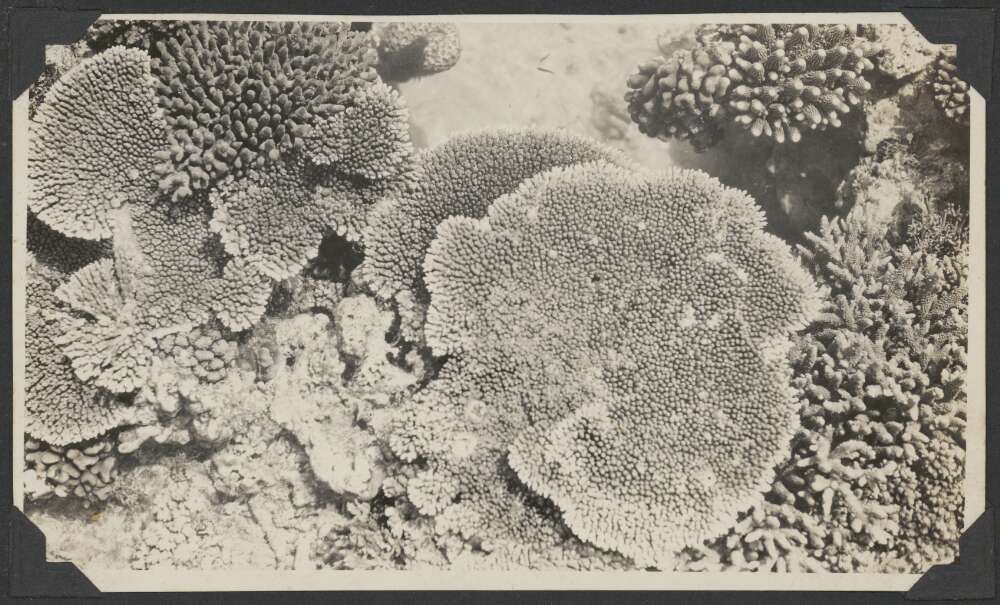

Dr Maurice Yonge described the actual work undertaken during the year on the Great Barrier Reef under four general headings. There was “observational and routine work”, which included taking regular hydrographic measurements, recording daily meteorological and tidal data, undertaking topographical and ecological surveys, and monitoring plankton stations. “Experimental work” involved all aspects of feeding, digestion, absorption, excretion and distribution of various corals and common animals on Low Isles and included large-scale experiments on the growth rate of corals. “Collecting work” involved, as the name suggests, collecting specimens, particularly plankton, as well as general dredging and trawling around Low Isles reef.[1] “Economic work” looked at aspects of the reef that had commercial potential.

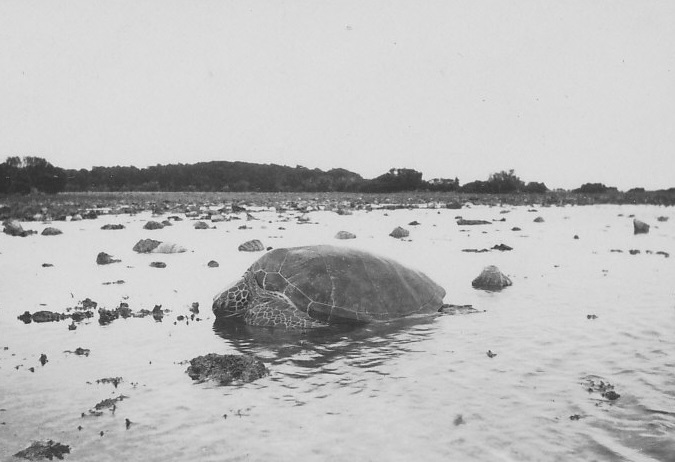

Two Australians, F.W. Moorhouse and A.G. Nicholls, focused on this “economic work”. They studied animals of direct economic importance, completing detailed investigations into the growth, breeding period and habits of trochus and the back-lip pearl oyster, respectively. They also looked at the spawning of bêche-de-mer, and rock and mangrove oysters, and observed fluctuations in edible fish populations around Low Isles and between Cairns and Cooktown. Information was collected about the potential for harvesting turtle and dugong for economic purposes.[2]

By modern standards, much of the research was conducted using relatively unsophisticated equipment. The diving apparatus used to explore the sea bed was one example. Yonge thought the helmet resembled “a dustbin with a handle at the top and plate glass windows in front.”[3] The diver, dressed only in a bathing costume and canvas shoes, had the helmet lowered over his head, before being weighted down with lead weights. With air being pumped down to the diver using a basic car-tyre pump, it was possible to remain below water for extended periods of time, depending on the stamina of those in the boat above doing the pumping. One of the drawbacks of the diving helmet was that it had two glass viewing panels that were positioned in such a way that made depth perception impossible, making the diver prone to falls.[4] The diving helmet used on the expedition is now housed at the Museum of Tropical Queensland, in Townsville.

Life on a Tropical Island

The expedition party arrived on Low Isles in midwinter. They were surprised at how cold the weather was, having only packed clothing for tropical conditions, and were hammered by winds that regularly averaged 20 to 40 miles an hour, which made working from small boats unpleasant. Before long though, they began to wish for a return of the cool winds and by November tropical thunderstorms heralded the coming summer, which brought with it unbearable heat and humidity. Yonge wrote that between December and April, he estimated they had received about 80 inches of rain:

When the water was not falling, it was rising; the summer sun drew up the moisture from the earth and sea until the atmosphere was saturated… We lived in a perpetual Turkish bath.[5]

Yonge recalled that there was always a feeling that there was not going to be sufficient time to complete all the planned work and consequently the team worked all day and often all, or part, of the night, explaining:

Our work was never finished… Work of this intensity in such a climate was hard; one felt perpetually tired; every action demanded a tremendous initial effort. It was not until I left the island that I realised fully under what a strain we had been living for many months past. At the same time it was work that made life endurable: without that compelling interest, the continuous association of so many people in such an endeavour would have been impossible.[6]

Although there were few mosquitoes, sandflies were a constant trial. Sunburn was common among those who joined the expedition later, and frequent cuts and abrasions sustained from contact with corals tended to fester when re-exposed to seawater. Frederick Russell, the deputy leader of the expedition, was stung by a box jellyfish and had to be carried back to camp on a makeshift stretcher. When Frederick lost consciousness, his wife Gweneth was told that the only way to save his life was to amputate his leg.[7] In what must have been a difficult decision, she refused to consent to an amputation, and thankfully, Frederick made a full recovery.

By summer, the heat and humidity proved physically exhausting for many of the expeditioners, and towards the end of the expedition, both Sheina Marshall and Mattie Yonge required short stays in Port Douglas Hospital.[8]

Despite the difficulties, the mood of the expedition members’ remained buoyant. According to Yonge, what had kept them going was

…the thrill of investigating and living amongst animals of which we had read so much but had never expected to see.[9]

The title for this chapter was inspired by one of the books from the Sir Charles Maurice Yonge Collection: The Sun, the Sea and Tomorrow by F.G. Walton Smith and Henry Chapin, 1955.

- Charles Maurice Yonge, “The Great Barrier Reef Expedition, 1928 – 1929,” Reports of the Great Barrier Reef Committee 3, (1931): 16-17. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/156399. ↵

- Yonge, “Great Barrier Reef,” 18. ↵

- Charles Maurice Yonge, A Year on the Great Barrier Reef, (London: Putnam, 1930), 99. ↵

- Yonge, A Year, 101. ↵

- Yonge, 35. ↵

- Yonge, 36. ↵

- Gerald T. Boalch, “Frederick Stratten Russell, FRS (1897-1984): A Distinguished Scientist and Stimulating Leader,” Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 90, no. 6 (2010): 1074, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315410000627. ↵

- Yonge, “Great Barrier Reef,” 12. ↵

- Yonge, A Year, 37. ↵