4.4 Sample Size and Sampling Techniques

While there are no set guidelines to determine sample size in qualitative research, the ideal sample size depends on the questions being asked, the theoretical framework, the study design, the type of data that is gathered, the available resources, and the amount of time.50 Some qualitative studies may involve only a single case, while others may involve a small number of cases, such as a few individuals or groups. The goal of a qualitative study is not to generalise the findings to a larger population but rather to provide a detailed and in-depth understanding of the specific case or cases being studied. A sufficient sample size in qualitative research is one that allows for the detailed, case-oriented analysis that is a characteristic of all qualitative enquiry but also not too small to result in a novel and deeply nuanced knowledge of experience.50 The minimum number and types of sample units needed in qualitative research cannot be predetermined using calculations or power analyses.50 Rather, the basic methodological principle in qualitative research is to achieve saturation, which means you keep sampling until you stop learning new details or insights about the phenomenon under investigation.51 The concept of saturation originated from grounded theory but is now accepted across various approaches in qualitative research. In general, you should keep asking participants until the area of interest is saturated and until you hear nothing new.43,51 The number of participants, therefore, depends on the richness of the data. A systematic review of empirical results showed that qualitative studies that had 9-17 interviews or 4-8 focus group discussions reached saturation.52 Nonetheless, the sampling technique is essential given that data cannot be obtained from everyone in the population.

There are four major sampling techniques:

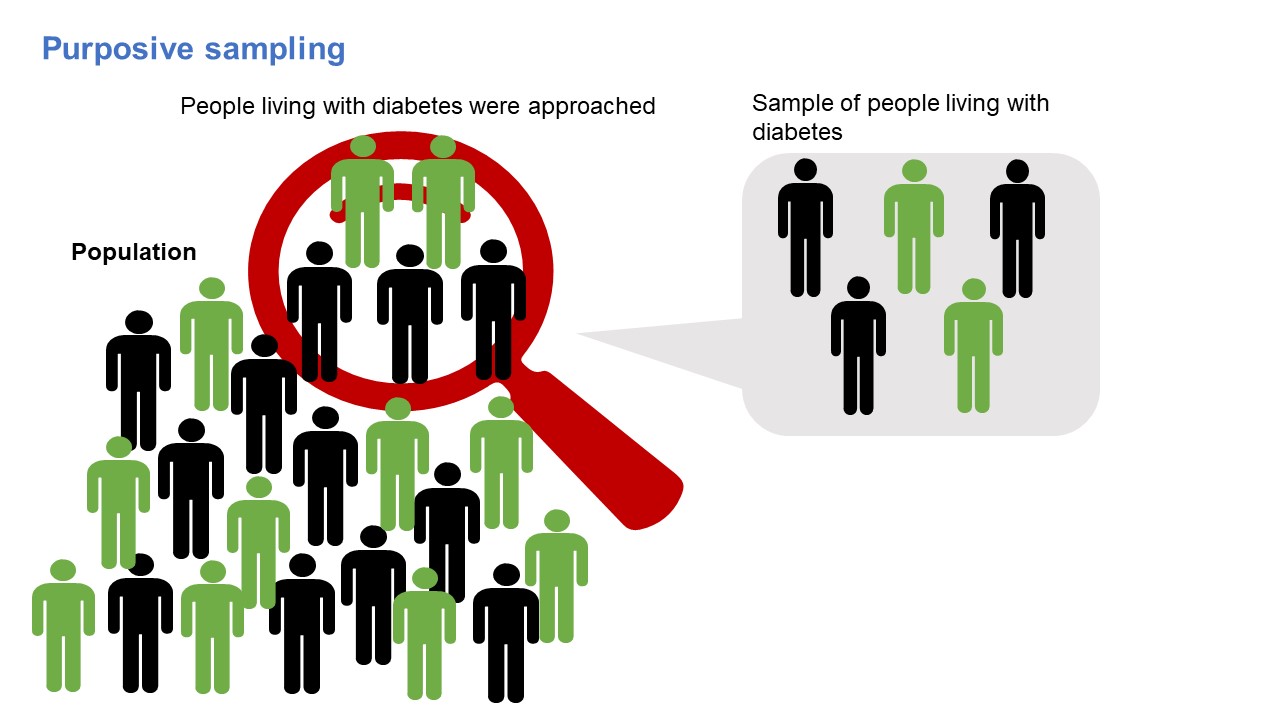

- Purposive sampling is also known as purposeful or selective sampling. It entails the deliberate, purposeful recruitment of individuals who can offer in-depth, precise details on the topic being studied.53 There are numerous purposive sampling techniques. Examples include typical, extreme or deviant, critical, maximum variation and homogenous sampling.54 Typical case highlights or illustrates what is normal, typical or average in a case. The purpose is to describe what is typical to those who are unfamiliar with the concept or phenomenon.54 Extreme or deviant is used when researchers want to explore deviations or outliers from the norm regarding a particular subject.54 On the other hand, a critical case involves exploring one case to provide insight into other similar cases.54 The maximum variation sampling technique is used if the research aims to uncover core and shared elements/ themes that cut across a diverse sample while simultaneously offering the opportunity to identify divergent opinions.54 In contrast, homogenous sampling focuses on people of similar backgrounds and experiences. It reduces variation and is mainly used for focus group discussions.54 An example of purposive sampling is the study by Adu et al., 2019 which investigated the common gaps in skills and self-efficacy for diabetes self-management and explored other factors which serve as enablers of and barriers to achieving optimal diabetes self-management.55 The study utilised a maximum variation purposive sampling technique to recruit participants into the study.55 Figure 4.3 illustrates purposive sampling, where researchers wish to explore the perceptions of people living with diabetes. Diabetic patients were approached and recruited into the study.

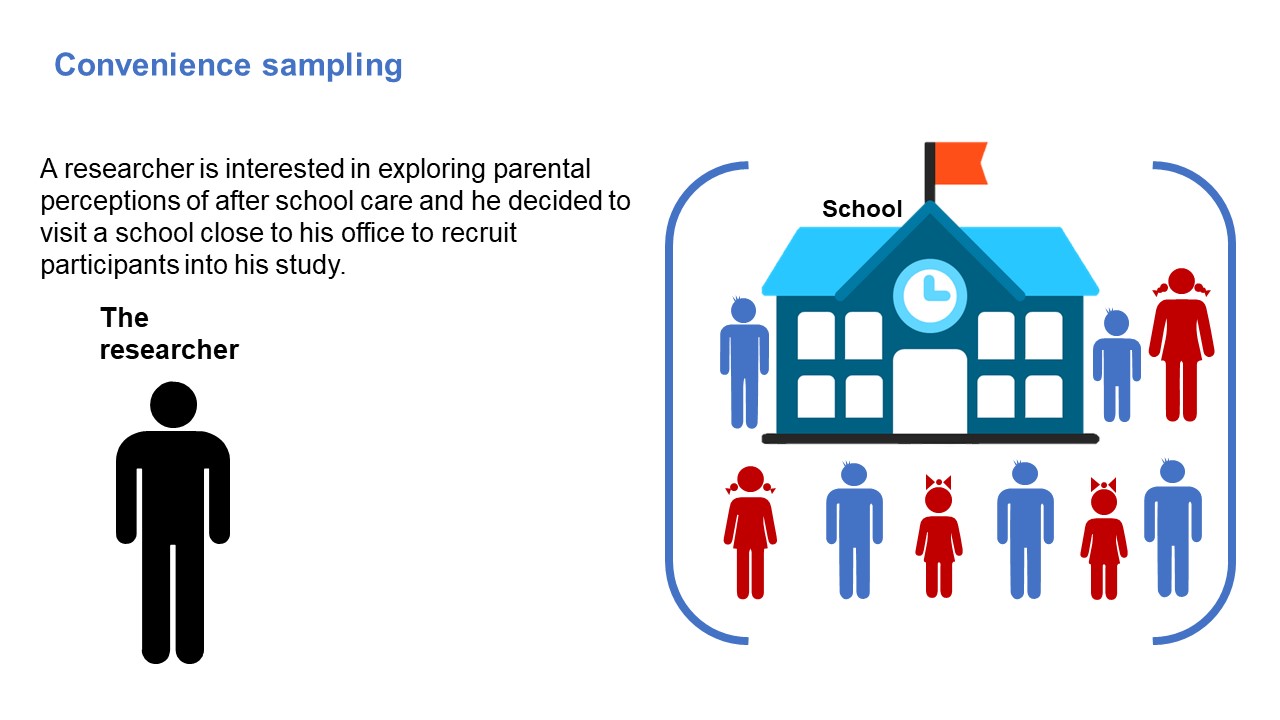

- Convenience sampling is a technique used to recruit participants who are representative of the population from which they are selected but chosen because they are easily accessible and convenient to the researchers rather than being randomly selected.56 Often this may include utilising geographic location, association with a facility/contact and resources that make participant recruitment convenient (Figure 4.4).56 This sampling technique saves time and effort but has low credibility.56 While convenience sampling is used in qualitative research, it can also be utilised in quantitative research, as stated in Chapter 3. In addition, it can also be used in mixed methods research which will be discussed in Chapter 5. For example, this study by Obasola and Mabawonku, 2018 used convenience sampling to select 1001 mothers attending maternity clinics at health facilities in Nigeria.57

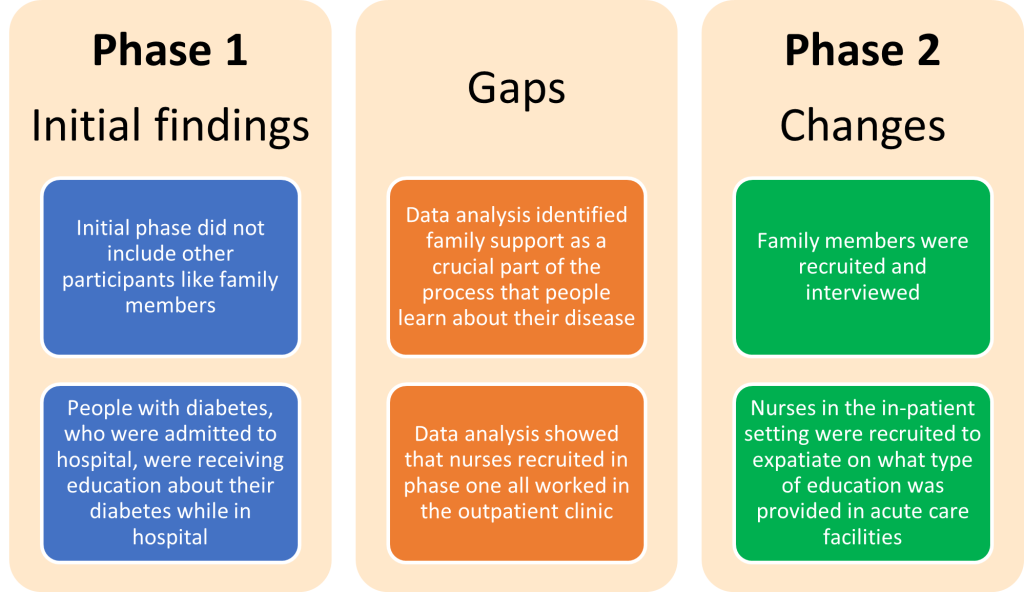

- Theoretical sampling is a data collection process controlled by a theory generation process.43 It involves the simultaneous collection, coding and analysis of data to identify the next stage of data collection and where to find the participants to develop the emerging theory.43 It is the principal strategy for the grounded theory approach.43 According to theoretical sampling, new goals for data collection are determined by the information gathered from the previous sample. It entails seeing emerging ideas in the data that is being produced and using those ideas to direct where, how, and from whom more data should be gathered and with what emphasis.46 For example, the study by Ligita et al. 2019 utilised theoretical sampling in the study that sought to generate a theory to explain the process by which people with diabetes learn about their disease in Indonesia.58 The study was conducted in three phases, with a total of twenty-six participants. In the first phase, participants were recruited via purposive sampling, and data from the first phase led to further data gathering. Theoretical sampling was used to select the next data from 17 participants based on the data analysis 58. Phase three was directed via theoretical sampling, with two new participants recruited into the study.58 In Figure 4.5, two examples of how theoretical sampling was used in the study have been highlighted.59

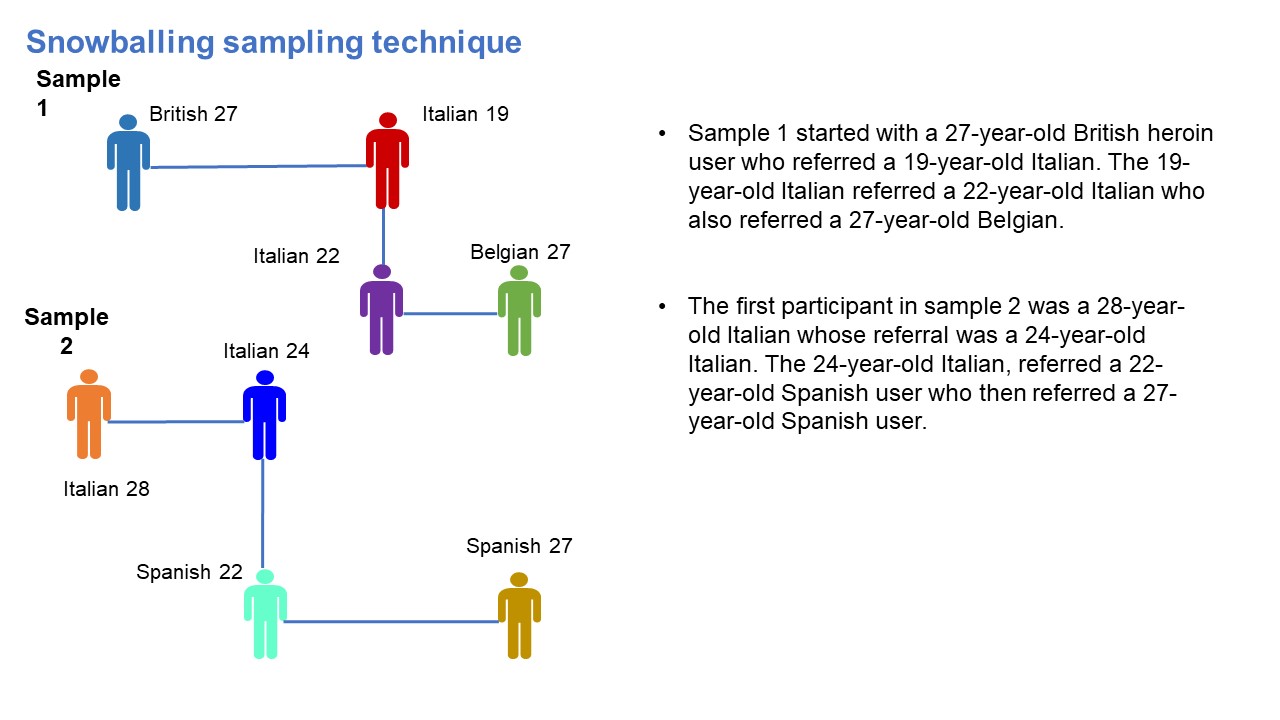

- Snowball sampling – This technique is used when it is hard to reach potential participants e.g. members of minority groups. The researcher initially contacts a few potential participants and asks them to provide contact details of people or refer people they know who meet the selection criteria.60 These identified or named individuals are then recruited into the study. A simple way to consider this technique is to think of how a small snowball rolls down a hill and gets bigger as it gathers more snow.60 An example is the study by Kaplan, Korf and Sterk, 1987 which describes the temporal and social contexts of Heroin-using populations in two Dutch cities.61 While the article may be several years old, the graphical presentation and description of the snowballing technique are still valid (Figure 4.6).61