6.3 Principles of Research Ethics

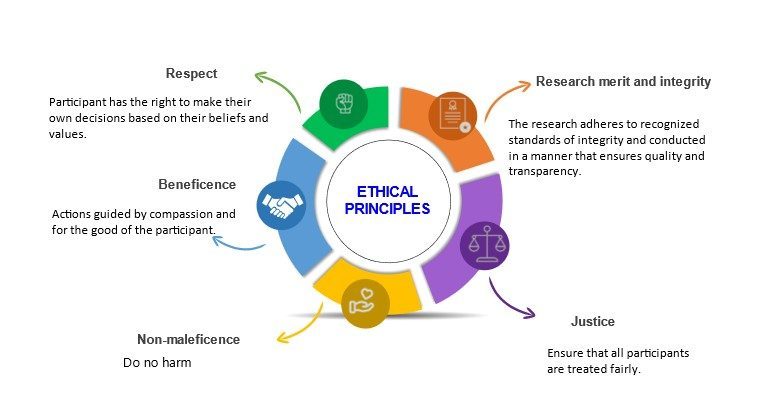

There are general ethical principles that guide and underpin the proper conduct of research. The term “ethical principles” refers to those general rules that operate as a foundational rationale for the numerous specific ethical guidelines and assessments of human behaviour.7 The National Statement on ‘ethical conduct in human research’ states that ethical behaviour entails acting with integrity, motivated by a deep respect and concern for others.8 Before research can be conducted, it is essential for researchers to develop and submit to a relevant human research ethics committee a research proposal that meets the National Statement’s requirements and is ethically acceptable. There are five key ethical research principles – respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice8,9 (Figure 6.1). These principles are universal, which means they apply everywhere in the world, without national, cultural, legal, or economic boundaries. Therefore, everyone involved in human research studies should understand and follow these principles.

Research merit and integrity

Research merit and integrity relate to the quality or value of a study in contributing to the knowledge base of a particular field or discipline. 8,9 This is determined by the originality and significance of the research question, the soundness and appropriateness of the research methodology, the rigor and reliability of the data analysis, the clarity and coherence of the research findings, and the potential impact of the research on advancing knowledge or solving practical problems. Research must be developed with methods that are appropriate to the study’s objectives, based on a thorough analysis of the relevant literature, and conducted using facilities and resources that are appropriate for the study’s needs. In essence, research must adhere to recognised standards of integrity and be designed, reviewed and conducted in a manner that ensures quality and transparency.8 Examples of unacceptable practices include plagiarism through appropriation or use of the ideas or intellectual property of others; falsification by creating false data or other aspects of research (including documentation and consent of participants); distortion through improper manipulation and/or selection of data, images and/or consent.

Respect for persons

Respect for humans is an acknowledgement of their inherent worth, and it refers to the moral imperative to regard the autonomy of others.8,10 Respect entails taking into account the well-being, beliefs, perspectives, practises, and cultural heritage of persons participating in research, individually and collectively. It involves respecting the participants’ privacy, confidentiality, and cultural sensitivity.8 Respect also entails giving adequate consideration to people to make their judgements throughout the study process. In cases where the participants have limited capacity to make autonomous decisions, respect for them entails protecting them against harm.8 This means that all participants in research must participate voluntarily without coercion or undue influence, and their rights, dignity and autonomy should be respected and adequately protected.

Beneficence

The ethical principle that requires actions that promote the well-being and interests of others is known as beneficence.10 It is the fundamental premise underlying all medical health care and research.8 Beneficence requires the researcher to weigh the prospective benefits and hazards and make certain that projects have the potential for net benefit over harm.8,10 Researchers are responsible for: (a) structuring the study to minimise the risks of injury or discomfort to participants; (b) explaining the possible benefits and dangers of the research to participants; and (c) the welfare of the participants in the research setting 8. Thus, the study participants must always be prioritised over the research methodology, even if this means invalidating data.8

Non-maleficence

This is the ethical principle that requires actions that avoid or minimize harm to others. According to the principle of non-maleficence, participating in a study shouldn’t do any harm to the research subject. This principle is closely related to beneficence; however, it may be difficult to keep track of any damage to study participants.11 Different types of harm could occur, including physical, mental, social, or financial harm. While the physical injury may be quickly recognised and then avoided or reduced, less evident issues such as emotional, social, and economic factors might hurt the subject without the researcher being aware.11 It is essential to note that all research involve cost to participants even if just their time, and each research study has the potential to hurt participants, hence it is important to ensure that the merit of research outweighs the costs and risks. There are five categories into which studies may be categorised based on the possible amount of injury or discomfort that they may expose the participants to.11

- No anticipated effects

- Temporary discomfort

- Unusual levels of temporary discomfort

- Risk of permanent damage

- Certainty of permanent damage

Justice

The concept of fairness and the application of moral principles to ensure equitable treatment. According to this research tenet, the researcher must treat participants fairly and always prioritise the needs of the research subjects over the study’s aim.8,11 Research participants must be fairly chosen, and that exclusion and inclusion criteria must be accurately stated in the research’s findings.8 In addition, there is no unjust hardship associated with participating in research on certain groups, and the participant recruitment method is fair. Furthermore, the rewards for research involvement are fairly distributed; research participants are not exploited, and research rewards are accessible to everybody equally.8