5.3 Video and media

Creating Video Lectures

Successful eLearning courses often use online lectures and other multimedia as methods of delivering course content. Video, whether teacher-created, licensed or sourced from open repositories, allows students flexibility in accessing resources and increases engagement and success. At JCU, we recommend you use Panopto to create your video content. Panopto provides secure video recordings, viewing, editing, sharing, and streaming capabilities, all from within LearnJCU.

A recent publication from TechSmith (TechSmith-Video-Viewer-Study-2021-Report), highlighted that respondents preferred videos of between 5 and 19 minutes in length, and used words such as “concise”, “interesting”, “engaging”, “interactive”, “easy-to-follow”, “relatable” and “innovative” to describe an engaging video.

Tips on video production

A 2014 paper by Guo, Kim and Rubin titled “How Video Production Affects Student Engagement: An Empirical Study of MOOC Videos”, presented an empirical study of how video production affected student engagement in 862 videos from four edX courses offered in the Fall 2012 to 128,000 students. Guo’s seven summarized recommendations from his 2014 blog post match the CPI’s guidance and experience:

Most importantly, do not aim for perfection – students appreciate enthusiasm and hearing authentic messages over a highly polished but robotic end product.

tips for using open-source video

Sometimes you may wish to incorporate open-source videos such as YouTube or Open Educational Resources (OERs). Here are a few tips for consideration when using these materials:

- Ensure video falls within fair dealing and copyright regulations

- Make sure you reference the resource appropriately

- Incorporate accessibility measures, such as captioning or transcripts where possible

- Watch the selected video from start to finish to ensure it’s appropriate

- Provide students with plenty of guidance and instruction for any activities associated with the video.

Content File Types Used in Web-enriched Courses

There are a variety of file types that will contribute to your course website. Depending on the content and media you select to complement your subject goals, you may capture and edit video files; develop written content; or simply distribute lecture notes in Microsoft Word, PowerPoint or in PDF format. The following file types are used most commonly by educators in course websites:

- PDF (Portable Document Format) files are very popular for distribution via the Internet. PDF files are excellent for disseminating papers, readings, or image-rich lecture materials and tend to be more accessible than many other types of web-based documents.

- Word files are often uploaded by educators to their course sites. However, as some students may not have similar or up-to-date programs with which to read DOC files, a safety measure would be to save Word files as PDF files. Note that doing so should keep nearly all formatting provided by Microsoft Word intact.

- PowerPoint is another file type popular among instructors. However, as PPT files are often completely inaccessible if the end-user does not have a compatible version, and because file sizes are generally much larger than is recommended, consider exporting the text or slides to Word (File > Send To > Microsoft Word), which gives the same content in a more manageable format. It is also possible to export a PowerPoint presentation to PDF which will open in a student’s web browser, rather than needing a program to open.

Low-bandwidth Teaching

Remote teaching and learning brings with it a number of considerations and challenges. If learners are able to connect to free/institutional networks (e.g., from local libraries, or on-campus student work areas), they will likely be able to access a safe, reliable, and robust internet connection. However, if these learners are relying on home-based connections, or live in remote locations, these will likely have a slower speed connection, and their service may be shared with others in their house (for work, education, or entertainment).

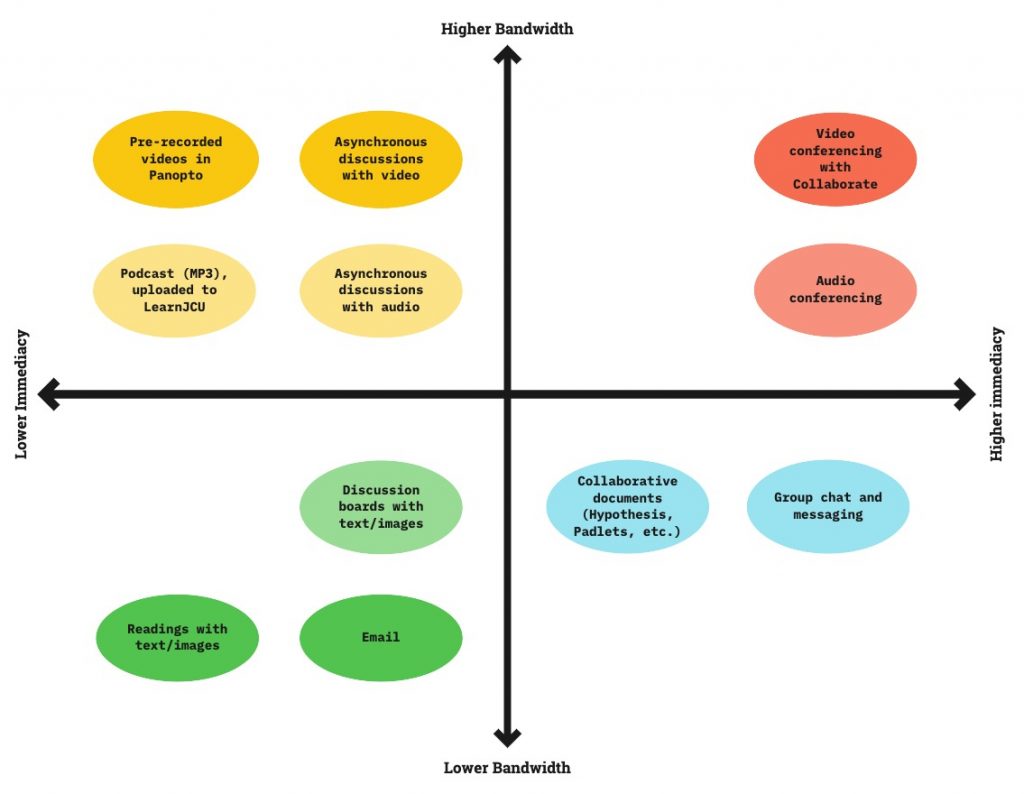

Daniel Stanford’s (2020) article provides some guidance on the issues of bandwidth and immediacy of information that require consideration when designing teaching for the online environment. His Bandwidth Immediacy Matrix (adapted below) prompts educators to consider different interaction or information dissemination technology approaches for students who may experience different bandwidth to ensure that subjects are more flexible and accessible for all students.

>> Definition of each coloured zone in the Bandwidth Immediacy Matrix

While considering activities that lower the bandwidth it’s also worth having a refresher on optimising images, PDFs, etc., for effective distribution before you upload them to your course or send them via email. Follow these links for more detail on how to optimise certain files.

- Optimising docs

- Optimising video files – Panopto will do this for you

- Optimising pdfs

- Optimising images

Tips on Course Web Page Design

Course subject sites need to meet a variety of requirements. Pages must contain quality information. In addition, the site should be visually pleasing, download quickly, and have intuitive navigational features.

For additional information on general style and layout issues, as well as issues specific to the Internet, consult Yale’s Web Style Guide.